еҚ°еәҰиҫІз”ўе“ҒеӨ–йҠ·йҮ‘йЎҚпјҲд»Ҙ2015е№ҙзҫҺе…ғе№ЈеҖјиЎЁйҒ”пјүгҖӮ еҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯеғұз”Ёдәәж•ёеңЁе…ЁеңӢеӢһеӢ•еҠӣеёӮе ҙдёӯзҡ„дҪ”жҜ”гҖӮ еҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯ пјҲиӢұиӘһпјҡagriculture in India пјүзҡ„жӯ·еҸІзҙ„еңЁеҚ—дәһзҹіеҷЁжҷӮд»Ј еҚіе·Ій–Ӣе§ӢгҖӮи©ІеңӢзҡ„иҫІжҘӯз”ўйҮҸдҪҚеұ…дё–з•Ң第дәҢгҖӮж №ж“ҡ2020-21иІЎж”ҝе№ҙеәҰзҡ„經жҝҹиӘҝжҹҘпјҢиҫІжҘӯеғұз”Ёдәәж•ёи¶…йҒҺи©ІеңӢеӢһеӢ•еҠӣзҡ„50%пјҢиҖҢз”ўеҖјеңЁеңӢе…§з”ҹз”ўжҜӣйЎҚ пјҲGDPпјүдёӯзҡ„дҪ”жҜ”зӮә20.2%гҖӮ[ 1]

еҚ°еәҰж–ј2016е№ҙзҡ„иҫІжҘӯ еҸҠзӣёй—ңзҡ„з•ңзү§жҘӯ гҖҒжһ—жҘӯ еҸҠжјҒжҘӯ зӯүзӣёй—ңйғЁй–Җзҡ„з”ўеҖјдҪ”GDPзҡ„17.5%пјҢж–ј2020е№ҙзҡ„еғұз”Ёдәәж•ёзҙ„дҪ”ж•ҙй«”еӢһеӢ•еҠӣзҡ„41.49%гҖӮ[ 2] [ 3] [ 4] [ 5] зҫҺеңӢ е’ҢдёӯеңӢ еүҮдҪҚеұ…第дәҢеҸҠ第дёүгҖӮ[ 6]

еҚ°еәҰж–ј2013е№ҙзҡ„зҡ„еҮәеҸЈеғ№еҖјзӮә380е„„зҫҺе…ғпјҢзӮәдё–з•Ң第7еӨ§еҮәеҸЈеңӢпјҢ第6еӨ§ж·ЁеҮәеҸЈеңӢгҖӮ[ 7] й–ӢзҷјдёӯеңӢ家 е’ҢжңҖдҪҺеәҰй–ӢзҷјеңӢ家 гҖӮ[ 7] ең’и—қ е’ҢеҠ е·ҘйЈҹе“ҒеҮәеҸЈеҲ°120еӨҡеҖӢеңӢ家пјҢдё»иҰҒйҠ·еҫҖж—Ҙжң¬ гҖҒжқұеҚ—дәһ гҖҒеҚ—дәһеҚҖеҹҹеҗҲдҪңиҒҜзӣҹ еңӢ家гҖҒжӯҗзӣҹ е’ҢзҫҺеңӢ гҖӮ[ 8] [ 9]

еҚ°еәҰжҳҜдё–з•ҢдёҠжңҖеӨ§зҡ„иҫІз”ўе“ҒеҮәеҸЈеңӢд№ӢдёҖгҖӮи©ІеңӢж–ј2024е№ҙ4жңҲиҮі7жңҲжңҹй–“зҡ„иҫІз”ўе“ҒеҮәеҸЈйҮ‘йЎҚйҒ”157.6е„„зҫҺе…ғгҖӮж–ј2023-24иІЎж”ҝе№ҙеәҰзҡ„иҫІз”ўе“ҒеҮәеҸЈйҮ‘йЎҚзӮә481.5е„„зҫҺе…ғгҖӮ2022-23иІЎж”ҝе№ҙеәҰе№ҙзҡ„иҫІз”ўе“ҒеҮәеҸЈйҮ‘йЎҚзӮә525е„„зҫҺе…ғгҖӮ2021-22иІЎж”ҝе№ҙеәҰзҡ„иҫІз”ўе“ҒеҮәеҸЈйҮ‘йЎҚзӮә502е„„зҫҺе…ғпјҢијғ2020-21иІЎж”ҝе№ҙеәҰзҡ„413е„„зҫҺе…ғеўһй•·20%гҖӮ[ 10]

еҚ°еәҰж–јиҫІжҘӯжҙ»еӢ•дёӯдҪҝз”Ёзҡ„иҫІи—Ҙ е’ҢеҢ–еӯёиӮҘж–ҷ жңүеҠ©ж–јжҸҗй«ҳдҪңзү©з”ҹз”ўеҠӣпјҢдҪҶе…¶дёҚеҸ—з®ЎеҲ¶е’ҢйҒҺеәҰдҪҝз”Ёзҡ„зөҗжһңпјҢйҖ жҲҗеҗ„зЁ®з”ҹж…Ӣзі»зөұ е’ҢеҡҙйҮҚеҒҘеә·зҡ„е•ҸйЎҢгҖӮ[ 11] [ 12] зҷҢз—Ү жӯёеӣ ж–јиҫІи—Ҙе°ҺиҮҙгҖӮйҖҷдәӣеҢ–еӯёзү©иіӘе·Іиў«иӯүжҳҺжңғе°ҺиҮҙDNA жҗҚеӮ·гҖҒжҝҖзҙ зҙҠдәӮпјҢеҸҠе…Қз–«зі»зөұ еҠҹиғҪйҷҚдҪҺгҖӮ[ 12] [ 12] ж®әиҹІеҠ‘ гҖҒйҷӨиҚүеҠ‘ е’Ңж®әзңҹиҸҢеҠ‘ гҖӮ[ 13] [ 12] ж—ҒйҒ®жҷ®йӮҰ жүҖдҪҝз”Ёзҡ„еҢ–иӮҘж•ёйҮҸзӮәеҚ°еәҰе…ЁеңӢ第дёҖгҖӮи©ІйӮҰдҪҝз”Ёзҡ„иҫІи—ҘдёӯжңүеӨҡзЁ®еӣ е…¶жҘөй«ҳжҜ’жҖ§еҸҠдҪҺеҚҠж•ёиҮҙжӯ»йҮҸ иҖҢиў«дё–з•ҢиЎӣз”ҹзө„з№” пјҲWHOпјүеҲ—зӮәIйЎһиҫІи—ҘпјҢйҖҷйЎһиҫІи—Ҙе·Іиў«дё–з•Ңеҗ„ең°пјҲеҢ…жӢ¬жӯҗжҙІ пјүзҰҒз”ЁгҖӮ[ 14] [ 15]

еҚ°еәҰиҫІж°‘жҢҮзҡ„жҳҜи©ІеңӢд»ҘзЁ®жӨҚиҫІдҪңзү©зӮәжҘӯиҖ…гҖӮ[ 16] дәәеҸЈжҷ®жҹҘ иҫІжҘӯжҷ®жҹҘ [ 17] [ 17] [ 18] [ 18]

еҚ°еәҰ2007е№ҙеңӢ家иҫІж°‘ж”ҝзӯ–е°ҮиҫІж°‘е®ҡзҫ©зӮәпјҡ[ 16]

ж–јжң¬ж”ҝзӯ–дёӯпјҢ"иҫІж°‘"жҢҮзҡ„жҳҜз©ҚжҘөеҫһдәӢзЁ®жӨҚиҫІдҪңзү©еҸҠз”ҹз”ўе…¶д»–еҲқзҙҡиҫІжҘӯе•Ҷе“Ғзҡ„經жҝҹе’Ң/жҲ–з”ҹиЁҲжҙ»еӢ•иҖ…пјҢеҢ…жӢ¬жүҖжңүиҫІжҘӯ經зҮҹиҖ…гҖҒиҖ•зЁ®иҖ…гҖҒиҫІжҘӯе·ҘдәәгҖҒдҪғиҫІгҖҒдҪғжҲ¶гҖҒ家зҰҪ家з•ңйЈјйӨҠиҖ…гҖҒжјҒж°‘гҖҒйӨҠиңӮдәәгҖҒең’дёҒгҖҒзү§ж°‘гҖҒйқһжі•дәәеғұз”ЁзЁ®жӨҚиҖ…е’ҢзЁ®жӨҚе·ҘдәәпјҢд»ҘеҸҠеҫһдәӢи ¶жҘӯ гҖҒи •иҹІйӨҠж®–гҖҒиҫІжһ—жҘӯзӯүеҗ„зЁ®иҫІжҘӯзӣёй—ңиҒ·жҘӯзҡ„дәәе“ЎгҖӮиҫІж°‘йӮ„еҢ…жӢ¬еҫһдәӢијӘиҖ•д»ҘеҸҠжңЁжқҗ收йӣҶгҖҒдҪҝз”Ёе’ҢйҠ·е”®д»ҘеҸҠе’ҢжңЁжқҗз„Ўй—ңзҡ„жһ—жҘӯе·ҘдҪңзҡ„йғЁиҗҪ家еәӯ/еҖӢдәәгҖӮ

然иҖҢжӯӨе®ҡзҫ©дёҰжңӘеҸ—еҲ°жҺЎз”ЁгҖӮ[ 16]

з”ұе·ҰдёҠй ҶжҷӮйҮқж–№еҗ‘移еӢ• - жү“з©Җ, ж‘ҳжЈүиҠұ, ж•ҙзҗҶзЁ»з”°еҸҠжҺЎиҢ¶

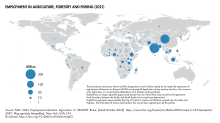

е…ЁзҗғиҫІжҘӯгҖҒжһ—жҘӯе’ҢжјҒжҘӯж–ј2021е№ҙзҡ„е°ұжҘӯдәәж•ёгҖӮйҖҷдәӣйғЁй–Җж–јеҚ°еәҰжүҖеғұз”Ёзҡ„дәәж•ёеңЁеҗ„еңӢдёӯеҗҚеҲ—еүҚиҢ…гҖӮ ж №ж“ҡзі§иҫІзө„з№” пјҲFAOпјүж–ј2014е№ҙзҷјдҪҲзҡ„дё–з•ҢиҫІжҘӯзөұиЁҲж•ёж“ҡпјҢеҚ°еәҰжҳҜдё–з•ҢдёҠе№ҫзЁ®й®®жһңпјҲеҰӮйҰҷи•ү гҖҒиҠ’жһң гҖҒз•ӘзҹіжҰҙ гҖҒжңЁз“ң гҖҒжӘёжӘ¬ пјүе’Ң蔬иҸңпјҲеҰӮй·№еҳҙиұҶ гҖҒз§Ӣи‘ө пјүе’ҢзүӣеҘ¶пјҢдё»иҰҒйҰҷж–ҷпјҲеҰӮиҫЈжӨ’ гҖҒи–‘ пјүе’Ңзә–з¶ӯдҪңзү©пјҲеҰӮй»ғйә» пјүпјҢдё»йЈҹпјҲеҰӮе°Ҹзұі пјҢи“–йә»жІ№ зұҪзҡ„жңҖеӨ§з”ҹз”ўеңӢгҖӮеҚ°еәҰжҳҜдё–з•Ңдё»иҰҒдё»зі§е°ҸйәҘ е’ҢеӨ§зұі зҡ„第дәҢеӨ§з”ҹз”ўеңӢгҖӮ[ 19]

еҚ°еәҰзӣ®еүҚжҳҜе…Ёзҗғе№ҫзЁ®д№ҫжһңгҖҒиҫІжҘӯзҙЎз№”еҺҹж–ҷгҖҒеЎҠж №дҪңзү©гҖҒиҺўжһң гҖҒйӨҠж®–йӯҡйЎһгҖҒйӣһиӣӢгҖҒжӨ°еӯҗ гҖҒз”ҳи”— е’ҢеӨҡ種蔬иҸңзҡ„第дәҢеӨ§з”ҹз”ўеңӢгҖӮ еҚ°еәҰж–ј2010е№ҙиў«еҲ—зӮәдё–з•ҢеүҚ5еӨ§иҫІжҘӯз”ҹз”ўеңӢд№ӢдёҖпјҢз”ўе“ҒзЁ®йЎһз№ҒеӨҡпјҲдҪ”80%пјүпјҢе…¶дёӯеҢ…жӢ¬е’–е•ЎиұҶ е’ҢжЈүиҠұ зӯүиЁұеӨҡ經жҝҹдҪңзү© гҖӮ[ 19] зүІз•ң е’Ң家зҰҪ иӮүйЎһз”ҹз”ўеңӢд№ӢдёҖпјҢд№ҹжҳҜжҲҗй•·зҺҮжңҖеҝ«зҡ„еңӢ家д№ӢдёҖгҖӮ[ 20]

ж–ј2008е№ҙзҷјиЎЁзҡ„дёҖд»Ҫе ұе‘ҠиҒІзЁұеҚ°еәҰзҡ„дәәеҸЈжҲҗй•·йҖҹеәҰи¶…йҒҺе…¶з”ҹз”ўеӨ§зұіе’Ңе°ҸйәҘзҡ„иғҪеҠӣгҖӮ[ 21] е·ҙиҘҝ е’ҢдёӯеңӢпјүйӮЈжЁЈжёӣе°‘ж”ҫд»»дё»йЈҹзҡ„и…җж•—/жөӘиІ»пјҢж”№е–„е…¶еҹәзӨҺиЁӯж–Ҫ дёҰжҸҗй«ҳиҫІжҘӯз”ҹз”ўеҠӣпјҢеҚіеҸҜиј•й¬ҶйӨҠжҙ»е…¶дёҚж–·еўһй•·зҡ„дәәеҸЈпјҢдёҰжңүйӨҳеҠӣе°Үе°ҸйәҘе’ҢеӨ§зұіеҮәеҸЈгҖӮ[ 22] [ 23]

жҲӘиҮі2011иІЎж”ҝе№ҙеәҰпјҢеҚ°еәҰз”ұж–јеӯЈйўЁ еӯЈзҜҖжӯЈеёёи’һиҮЁпјҢе…¶е°ҸйәҘз”ўйҮҸеүөжӯ·еҸІж–°й«ҳпјҢйҒ”еҲ°8,590иҗ¬еҷёпјҢжҜ”еүҚдёҖе№ҙеҗҢжңҹеўһеҠ 6.4%гҖӮеҚ°еәҰеӨ§зұіз”ўйҮҸеүөдёӢж–°зҙҖйҢ„пјҢйҒ”еҲ°9,530иҗ¬еҷёпјҢијғеүҚдёҖе№ҙеўһеҠ 7%гҖӮ[ 24] е°ҸжүҒиұҶ е’ҢиЁұеӨҡе…¶д»–дё»йЈҹзҡ„з”ўйҮҸд№ҹйҖҗе№ҙеўһеҠ гҖӮеҚ°еәҰиҫІж°‘ж–ј2011е№ҙиІЎж”ҝе№ҙеәҰзҡ„дәәеқҮе°ҸйәҘз”ўйҮҸзӮәзҙ„71е…¬ж–ӨгҖӮеӨ§зұіз”ўйҮҸзӮә80е…¬ж–ӨгҖӮ[ 25]

еҚ°еәҰж–ј2023-24иІЎж”ҝе№ҙеәҰзҡ„ж°ҙзЁ»з”ўйҮҸйҒ”еҲ°еүөзҙҖйҢ„зҡ„1.3782е„„еҷёпјҢй«ҳж–ј2022-23иІЎж”ҝе№ҙеәҰзҡ„1.3575е„„еҷёгҖӮе°ҸйәҘз”ўйҮҸд№ҹеүөдёӢж–°й«ҳпјҢйҒ”еҲ°1.1329е„„еҷёпјҢй«ҳж–јеүҚдёҖе№ҙзҡ„1.1055 е„„еҷёгҖӮ[ 26]

еҚ°еәҰж–ј2013е№ҙеҮәеҸЈеғ№еҖј390е„„зҫҺе…ғзҡ„иҫІз”ўе“ҒпјҢдҪҝе…¶жҲҗзӮәе…Ёзҗғ第7еӨ§иҫІз”ўе“ҒеҮәеҸЈеңӢе’Ң第6еӨ§ж·ЁеҮәеҸЈеңӢгҖӮ[ 7] [ 7] [ 7] йқһжҙІ гҖҒе°јжіҠзҲҫ гҖҒеӯҹеҠ жӢүеңӢ е’Ңдё–з•Ңе…¶д»–ең°еҚҖеҮәеҸЈзҙ„200иҗ¬еҷёе°ҸйәҘе’Ң210иҗ¬еҷёеӨ§зұігҖӮ[ 24]

еҚ°еәҰж–ј2023е№ҙеҮәеҸЈеӨ§зұійҮ‘йЎҚзӮә104.6е„„зҫҺе…ғпјҢжҺ’еҗҚе…Ёзҗғ第дёҖгҖӮдәһеӨӘең°еҚҖ第дәҢеӨ§зұіеҮәеҸЈеңӢжҳҜжі°еңӢ пјҢеҗҢе№ҙеҮәеҸЈйҮ‘йЎҚзӮә51.2е„„зҫҺе…ғгҖӮ[ 27]

ж°ҙз”ўйӨҠж®–е’ҢжјҒжҘӯжҳҜеҚ°еәҰжҲҗй•·жңҖеҝ«зҡ„з”ўжҘӯд№ӢдёҖгҖӮ еҚ°еәҰж–ј1990е№ҙиҮі2010е№ҙжңҹй–“зҡ„йӯҡйЎһжҚ•ж’ҲйҮҸеўһеҠ дёҖеҖҚпјҢж°ҙз”ўйӨҠж®–з”ўйҮҸеўһеҠ е…©еҖҚгҖӮ еҚ°еәҰж–ј2008е№ҙжҳҜдё–з•Ң第6еӨ§жө·жҙӢе’Ңж·Ўж°ҙжҚ•ж’ҲжҘӯз”ҹз”ўеңӢе’Ң第дәҢеӨ§ж°ҙз”ўйӨҠж®–йЎһз”ҹз”ўеңӢгҖӮеҚ°еәҰеҗ‘е…Ёзҗғиҝ‘дёҖеҚҠзҡ„еңӢ家еҮәеҸЈ60иҗ¬еҷёйӯҡз”ўе“ҒгҖӮ[ 28] [ 29] [ 30] [ 31]

еҚ°еәҰеңЁйҒҺеҺ»60е№ҙдёӯзҡ„жҹҗдәӣиҫІз”ўе“ҒжҜҸе…¬й ғе№іеқҮз”ўйҮҸеңЁе…ЁеңӢе‘ҲзҸҫз©©е®ҡжҲҗй•·гҖӮйҖҷзЁ®жҲҗе°ұдё»иҰҒдҫҶиҮӘеҚ°еәҰзҡ„з¶ иүІйқ©е‘Ҫ гҖҒж”№е–„йҒ“и·Ҝе’Ңзҷјйӣ»еҹәзӨҺиЁӯж–ҪгҖҒзҹҘиӯҳеҸ–еҫ—е’Ңж”№йқ©гҖӮ[ 32] е·Ій–ӢзҷјеңӢ家 е’Ңе…¶д»–й–ӢзҷјдёӯеңӢ家иҫІе ҙжңҖдҪіж°ёзәҢиҫІдҪңзү©з”ўйҮҸзҡ„30%иҮі60%гҖӮ[ 33] [ 34] [ 35]

ж–јжҜ”е“ҲзҲҫйӮҰзҡ„иҖ•зЁ®зЁ®жҖ§ еә«зҲҫзұі еҚ°еәҰзҡ„дё»иҰҒиҫІз”ўе“Ғд№ӢдёҖ - еӨ§зұіеӣ еӯЈйўЁжЁЎејҸзҡ„иҪүи®ҠиҖҢз”ҹз”ўеҸ—еҲ°еҪұйҹҝгҖӮеңЁ2022е№ҙпјҢи©ІеңӢжқұйғЁеҗ„йӮҰпјҲеҢ—ж–№йӮҰ гҖҒжҜ”е“ҲзҲҫйӮҰ е’ҢеҘ§иҝӘи–©йӮҰ пјү經жӯ·йҒҺй«ҳжә«е’ҢйҷҚж°ҙ дёҚи¶іпјҢиҖҢеҚ°еәҰдёӯйғЁе’ҢеҚ—йғЁең°еҚҖиҝ‘е№ҫеҖӢжңҲдҫҶйҷҚж°ҙйҒҺеӨҡпјҢе°ҺиҮҙеҚ—йғЁең°еҚҖзҡ„е–ҖжӢүжӢүйӮҰ гҖҒеҚЎзҙҚеЎ”еҚЎйӮҰ е’ҢдёӯеӨ®йӮҰ зҷјз”ҹжҙӘж°ҙгҖӮ[ 36] [ 37] [ 38]

еҗ йҷҖж•ҷ зҡ„ж №жң¬ж•ҷе…ёгҖҠеҗ йҷҖ гҖӢжҸҗдҫӣдёҖдәӣеҚ°еәҰжңҖж—©зҡ„иҫІжҘӯж–Үеӯ—иЁҳйҢ„гҖӮдҫӢеҰӮе…¶дёӯгҖҠжўЁдҝұеҗ йҷҖ гҖӢжҸҸиҝ°иҖ•дҪңгҖҒдј‘иҖ•гҖҒзҒҢжәүгҖҒж°ҙжһңе’Ң蔬иҸңзЁ®жӨҚгҖӮе…¶д»–жӯ·еҸІиӯүж“ҡйЎҜзӨәеҚ°еәҰжІі и°·зЁ®жӨҚйҒҺж°ҙзЁ»е’ҢжЈүиҠұпјҢеңЁжӢүиіҲж–ҜеқҰйӮҰ зҡ„еҚЎеҲ©зҸӯз”ҳ йқ’йҠ…жҷӮд»Ј зҡ„иҖ•дҪңйҒәи·ЎгҖӮ [ 39] жўөж–Ү ж–ҮзҚ» -гҖҠBhumivargahaгҖӢпјҲжҺЁжё¬е·Іжңү2,500е№ҙжӯ·еҸІпјүпјҢе°ҮиҫІең°еҲҶзӮә12йЎһпјҡurvaraпјҲиӮҘжІғпјүгҖҒusharaпјҲиІ§зҳ пјүгҖҒmaruпјҲжІҷжј пјүгҖҒaprahataпјҲдј‘иҖ•пјүгҖҒshadvalaпјҲиҚүең°пјүгҖҒpankikalaпјҲжіҘжҝҳпјү гҖҒjalaprayahпјҲж°ҙпјүгҖҒkachchahaпјҲй„°иҝ‘ж°ҙпјүгҖҒsharkaraпјҲе……ж»ҝйөқеҚөзҹіе’ҢзҹізҒ°зҹізўҺзүҮпјүгҖҒsharkaravatiпјҲжІҷең°пјүгҖҒnadimatrukaпјҲжІіж°ҙпјүе’ҢdevamatrukaпјҲйӣЁйӨҠпјүгҖӮдёҖдәӣиҖғеҸӨеӯёе®¶иӘҚзӮәеӨ§зұіж–је…¬е…ғеүҚе…ӯеҚғе№ҙеңЁжҒ’жІі жІҝеІёиў«дәәйЎһйҰҙеҢ–гҖӮ[ 40] еӨ§йәҘ гҖҒзҮ•йәҘ е’Ңе°ҸйәҘ пјүе’ҢиұҶйЎһпјҲе°ҸжүҒиұҶе’Ңй·№еҳҙиұҶпјүд№ҹжҳҜеҰӮжӯӨгҖӮ[ 41] иҠқйә» гҖҒдәһйә» зұҪгҖҒз•Әзҙ…иҠұ гҖҒиҠҘжң« гҖҒи“–йә»гҖҒз¶ иұҶ гҖҒй»‘иұҶ зЎ¬зҡ®иұҶ гҖҒжңЁиұҶ гҖҒиұҢиұҶ гҖҒ家еұұ黧иұҶ пјҲkhesariпјүгҖҒиғЎиҳҶе·ҙ гҖҒжЈүиҠұгҖҒжЈ— гҖҒи‘Ўиҗ„ гҖҒжӨ°жЈ— гҖҒиҸ иҳҝиңң гҖҒиҠ’жһң гҖҒжЎ‘и‘ҡ е’Ңй»‘жқҺеӯҗгҖӮ[ 41] ж°ҙзүӣ еҸҜиғҪеңЁ5,000е№ҙеүҚе°ұиў«еҚ°еәҰдәәйҰҙеҢ–гҖӮ[ 42]

дёҖдәӣ科еӯёе®¶зЁұеҚ°еәҰеҚҠеі¶ ж–ј10,000-3,000е№ҙеүҚеҚіжҷ®йҒҚеӯҳеңЁиҫІжҘӯпјҢдёҰи·Ёи¶ҠеҢ—йғЁиӮҘжІғзҡ„е№іеҺҹеҗ‘еӨ–蔓延гҖӮдҫӢеҰӮдёҖй …з ”з©¶е ұе‘ҠжҸҗеҮәеҚ°еәҰеҚ—йғЁеқҰзұізҲҫйӮЈйғҪйӮҰ гҖҒе®үеҫ·жӢүйӮҰ е’ҢеҚЎзҙҚеЎ”еҚЎйӮҰзҡ„12еҖӢең°й»һпјҢжңүжҳҺзўәзҡ„иӯүж“ҡиӯүжҳҺе°ҚиұҮиұҶ (Vigna radiata)гҖҒеҚ°еәҰиұҶ (Macrotyloma uniflorum)гҖҒе°ҸзұіиҚү (Brachiaria ramosaе’ҢSetaria verticillata)гҖҒе°ҸйәҘ (Triticum dicoccumгҖҒTriticum durum/aestivum)гҖҒеӨ§йәҘ (Hordeum vulgare)гҖҒе°ҸжүҒиұҶ (Lablab purpureus)гҖҒй«ҳзІұ (Sorghum bicolor)гҖҒзҸҚзҸ зІҹ (Pennisetum glaucum)гҖҒжүӢжҢҮе°Ҹзұі (Eleusine coracana)гҖҒжЈүиҠұ (Gossypium sp.)гҖҒдәһйә» (Linum sp.) д»ҘеҸҠжЈ— (Ziziphus) е’Ңе…©зЁ®и‘«иҳҶ科жӨҚзү© (Cucurbitaceae) зҡ„зЁ®жӨҚгҖӮ[ 43] [ 44]

жңүдәӣдәәиҒІзЁұеҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯе§Ӣж–јиҘҝе…ғеүҚ9,000е№ҙпјҢжәҗиҮӘж—©жңҹжӨҚзү©зЁ®жӨҚе’ҢдҪңзү©йҰҙеҢ–гҖӮ[ 45] [ 46] [ 47] [ 48] [ 48] [ 49] зі– е’Ңз”ҳи”— иҫІжҘӯеј•йҖІеҚ°еәҰгҖӮ[ 50] [ 51] [ 52]

е…Ёзҗғж–ј18дё–зҙҖд»ҘеүҚзҡ„дё»иҰҒз”ҳи”—зЁ®жӨҚең°еңЁеҚ°еәҰгҖӮдёҖдәӣе•Ҷдәәй–Ӣе§ӢйҖІиЎҢзі–зҡ„иІҝжҳ“пјҢзі–еңЁ18дё–зҙҖзҡ„жӯҗжҙІжҳҜдёҖзЁ®еҘўдҫҲе“Ғе’ҢжҳӮиІҙзҡ„йҰҷж–ҷпјҢ然еҫҢй–Ӣе§ӢеңЁжӯҗжҙІжөҒиЎҢпјҢдёҰеңЁ19дё–зҙҖйҖҗжјёжҲҗзӮәе…Ёдё–з•Ңзҡ„з”ҹжҙ»еҝ…йңҖе“ҒгҖӮз”ҳи”—зЁ®жӨҚең’пјҢеҰӮеҗҢжЈүиҠұиҫІе ҙпјҢжҲҗзӮә19дё–зҙҖе’Ң20дё–зҙҖеҲқеӨ§иҰҸжЁЎеј·иҝ«ејҸдәәйЎһйҒ·еҫҷпјҲзүҪж¶үеҲ°ж•ёд»Ҙзҷҫиҗ¬иЁҲзҡ„йқһжҙІ е’ҢеҚ°еәҰдәәеҸЈпјүзҡ„йҮҚиҰҒй©…еӢ•еҠӣпјҢд№ӢеҫҢеҮәзҸҫеҠ еӢ’жҜ”ең°еҚҖ гҖҒеҚ°еәҰжҙӢ е’ҢеӨӘе№іжҙӢ еі¶еңӢй–“зҡ„зЁ®ж—Ҹж··еҗҲгҖҒж”ҝжІ»иЎқзӘҒе’Ңж–ҮеҢ–жј”и®ҠгҖӮ[ 53] [ 54]

еңЁжҹҗзЁ®зЁӢеәҰдёҠпјҢеҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯзҡ„жӯ·еҸІе’ҢйҒҺеҺ»зҡ„жҲҗе°ұе°Қж–°дё–з•Ңзҡ„ж®–ж°‘дё»зҫ©гҖҒеҘҙйҡёеҲ¶е’ҢйЎһеҘҙйҡёеҲ¶зҡ„еҘ‘зҙ„еӢһе·ҘеҒҡжі•гҖҒеҠ еӢ’жҜ”ең°еҚҖжҲ°зҲӯд»ҘеҸҠ18дё–зҙҖе’Ң19дё–зҙҖзҡ„дё–з•Ңжӯ·еҸІеқҮйҖ жҲҗеҪұйҹҝгҖӮ[ 55] [ 56] [ 57] [ 58] [ 59]

йӣ–然еҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯеңЁзҸҫд»ЈеҫҢжңҹпјҲ19дё–зҙҖжң«еҲ°20дё–зҙҖеҲқпјүеҮәзҸҫдёҖдәӣеҒңж»ҜпјҢдҪҶзҚЁз«ӢеҫҢзҡ„еҚ°еәҰе…ұе’ҢеңӢд»Қ然иғҪеҲ¶е®ҡеҮәдёҖеҘ—е…Ёйқўзҡ„иҫІжҘӯиЁҲеҠғгҖӮ[ 60] [ 61]

жЈүиҠұжҺЎж”¶пјҢжЈүиҠұзӮәеҚ°еәҰеҸӨеҗүжӢүзү№йӮҰдёӯйғЁзҡ„經жҝҹдҪңзү© гҖӮ еҚ°еәҰеңЁзҚЁз«Ӣд№ӢеҫҢж–јзі§йЈҹе®үе…Ё ж–№йқўе·ІеҸ–еҫ—е·ЁеӨ§йҖІеұ•гҖӮеҚ°еәҰдәәеҸЈеўһеҠ е…©еҖҚпјҢиҖҢз©Җзү©зі§йЈҹз”ўйҮҸеўһеҠ дёүеҖҚд»ҘдёҠгҖӮдәәеқҮз©Җзү©зі§йЈҹж•ёйҮҸеӨ§е№…еўһеҠ гҖӮ

ж—ҒйҒ®жҷ®йӮҰеј•й ҳеҚ°еәҰзҡ„з¶ иүІйқ©е‘ҪпјҢдёҰиҙҸеҫ—"еҚ°еәҰзі§еҖү"зҡ„зҫҺиӯҪгҖӮ[ 62] еҚ°еәҰеңЁ1960е№ҙд»Јдёӯжңҹд№ӢеүҚдҫқиіҙйҖІеҸЈе’Ңзі§йЈҹжҸҙеҠ©дҫҶж»ҝи¶іеңӢе…§йңҖжұӮгҖӮдҪҶзҷјз”ҹеңЁ1965е№ҙе’Ң1966е№ҙе…©е№ҙдёӯзҡ„еҡҙйҮҚд№ҫж—ұдҝғдҪҝи©ІеңӢйҖІиЎҢиҫІжҘӯж”№йқ©пјҢдёҚеҶҚдҫқиіҙеӨ–жҸҙе’ҢйҖІеҸЈдҫҶдҝқйҡңзі§йЈҹе®үе…ЁгҖӮеҚ°еәҰжҺЎеҸ–зҡ„ж”№йқ©йҮҚй»һеңЁж–јйҒ”жҲҗзі§йЈҹиҮӘзөҰиҮӘи¶іпјҢеј•зҷјеҚ°еәҰз¶ иүІйқ©е‘Ҫ [ 62]

жңҖеҲқзҡ„з”ўйҮҸеўһй•·йӣҶдёӯеңЁеҚ°еәҰиҘҝйғЁзҡ„ж—ҒйҒ®жҷ®йӮҰгҖҒе“ҲйҮҢдәһзҙҚйӮҰ е’ҢеҢ—ж–№йӮҰзҡ„зҒҢжәүең°еҚҖгҖӮйҡЁи‘—иҫІж°‘е’Ңж”ҝеәңе®ҳе“Ўй—ңжіЁиҫІжҘӯз”ҹз”ўеҠӣе’ҢзҹҘиӯҳеӮіж’ӯпјҢи©ІеңӢзҡ„зі§йЈҹзёҪз”ўйҮҸжҝҖеўһгҖӮеҚ°еәҰдёҖе…¬й ғзҡ„е°ҸйәҘз”°ж–ј1948е№ҙе№іеқҮз”ўйҮҸзӮә0.8е…¬еҷёпјҢеҗҢжЁЈеңҹең°еҲ°1975е№ҙзҡ„з”ўйҮҸзӮә4.7е…¬еҷёгҖӮйҖҷзЁ®еҝ«йҖҹжҲҗй•·и®“еҚ°еәҰиғҪж–ј1970е№ҙд»ЈеҜҰзҸҫиҮӘзөҰиҮӘи¶ігҖӮд№ҹдҝғдҪҝе°ҸиҫІиғҪе°ӢжұӮйҖІдёҖжӯҘзҡ„жүӢж®өдҫҶеўһеҠ жҜҸе…¬й ғдё»зі§з”ўйҮҸгҖӮеҚ°еәҰиҫІз”°еҲ°2000е№ҙе·Ій–Ӣе§ӢжҺЎз”ЁжҜҸе…¬й ғеҸҜз”ў6еҷёе°ҸйәҘзҡ„е“ҒзЁ®гҖӮ[ 22] [ 63]

дҪҚж–је®үеҫ·жӢүйӮҰиҗҠеё•е…ӢеёҢпјҲLepakshiпјүжқ‘иҺҠзҡ„еҗ‘ж—Ҙи‘ө з”°гҖӮ еҚ°еәҰзЁ®жӨҚе°ҸйәҘжҲҗеҠҹеҫҢпјҢд№ҹе°Үз¶ иүІйқ©е‘Ҫж“ҙеұ•еҲ°еӨ§зұіз”ҹз”ўгҖӮдҪҶеӣ 當жҷӮзҡ„еҚ°еәҰзҒҢжәүеҹәзӨҺиЁӯж–ҪйқһеёёиҗҪеҫҢпјҢеҚ°еәҰиҫІж°‘й–Ӣе§ӢжҺЎжҺҳдә•еӨ§йҮҸжҠҪеҸ–ең°дёӢж°ҙ зҡ„ж–№ејҸгҖӮйҡЁи‘—еҲқжңҹеё¶дҫҶзҡ„з”ўйҮҸжҸҗеҚҮйҖҗжјёи¶Ёж–је№із·©пјҢеҲ©з”Ёең°дёӢж°ҙжҠҖиЎ“еңЁ1970иҮі1980е№ҙд»Јй–“й–Ӣе§ӢеҫҖеҚ°еәҰжқұйғЁзҡ„жҜ”е“ҲзҲҫйӮҰгҖҒеҘ§иҝӘи–©йӮҰе’ҢиҘҝеӯҹеҠ жӢүйӮҰ зӯүең°еӮіж’ӯгҖӮж”№иүҜзЁ®еӯҗе’Ңж–°жҠҖиЎ“зҡ„жҢҒзәҢжҖ§ж•ҲзӣҠдё»иҰҒзҷјз”ҹеңЁи©ІеңӢзҡ„зҒҢжәүиҫІең° - дҪ”е…ЁеңӢиҫІең°зҡ„дёүеҲҶд№ӢдёҖгҖӮеҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯж”ҝзӯ–еңЁ1980е№ҙд»ЈиҪүеҗ‘"ж №ж“ҡйңҖжұӮиҖҢз”ҹз”ўзҡ„жЁЎејҸ"пјҢе°ҮйҮҚй»һиҪүеҗ‘зЁ®жӨҚжІ№зұҪгҖҒж°ҙжһңе’Ң蔬иҸңзӯүиҫІз”ўе“ҒгҖӮиҫІж°‘й–Ӣе§ӢеңЁд№іиЈҪе“ҒгҖҒжјҒжҘӯе’Ңз•ңзү§жҘӯдёӯжҺЎз”Ёж”№йҖІж–№жі•е’ҢжҠҖиЎ“пјҢд»Ҙж»ҝи¶ідёҚж–·еўһй•·дәәеҸЈзҡ„еҗ„ејҸйңҖжұӮгҖӮ

е°Қж–јж°ҙзЁ»пјҢж”№иүҜзЁ®еӯҗе’Ңж”№иүҜиҫІжҘӯжҠҖиЎ“зҡ„жҢҒзәҢжҖ§ж•ҲзӣҠзҸҫеңЁеҫҲеӨ§зЁӢеәҰдёҠеҸ–жұәж–јеҚ°еәҰжҳҜеҗҰжңғзҷјеұ•еҹәзӨҺиЁӯж–ҪпјҢеҰӮзҒҢжәүз¶ІзөЎгҖҒйҳІжҙӘзі»зөұгҖҒеҸҜйқ зҷјйӣ»иғҪеҠӣгҖҒжҡўйҖҡзҡ„иҫІжқ‘е’ҢеҹҺеёӮйҒ“и·ҜгҖҒиғҪдҝқй®®зҡ„еҶ·и—Ҹеә«гҖҒзҸҫд»Јйӣ¶е”®жҘӯд»ҘеҸҠйЎҳж„Ҹд»Ҙ具競зҲӯжҖ§еғ№ж јж”¶иіјиҫІз”ўе“Ғзҡ„買家гҖӮеүҚиҝ°е№ҫй»һе·Іж—ҘжјёжҲҗзӮәеҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯж”ҝзӯ–зҡ„йҮҚй»һгҖӮ

еҚ°еәҰзҡ„зі§йЈҹе®үе…ЁжҢҮж•ёеңЁе…Ёзҗғ113еҖӢдё»иҰҒеңӢ家дёӯжҺ’еҗҚ第74гҖӮ[ 31]

еҚ°еәҰйҒәеӮіеӯёе®¶ MВ·SВ·ж–Ҝз“ҰзұізҙҚеқҰ еңЁз¶ иүІйқ©е‘ҪдёӯжӣҫзҷјжҸ®йҮҚиҰҒиІўзҚ»гҖӮ ж–°еҫ·йҮҢйӣ»иҰ–еҸ° пјҲNDTVпјүж–ј2013е№ҙе°Үд»–и©•зӮәеҚ°еәҰ25дҪҚеңЁдё–еӮіеҘҮдәәзү©д№ӢдёҖпјҢд»ҘиЎЁеҪ°д»–е°ҚиҫІжҘӯпјҢе’Ңи®“еҚ°еәҰжҲҗзӮәзі§йЈҹиҮӘзөҰиҮӘи¶іеңӢ家зҡ„еӮ‘еҮәиІўзҚ»гҖӮ[ 64]

дҪҚж–је®үеҫ·жӢүйӮҰзҡ„зҒҢжәүжё йҒ“гҖӮзҒҢжәүе°Қж–јеҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯжңүйқһеёёйҮҚиҰҒзҡ„дҪңз”ЁгҖӮ йҢ«йҮ‘йӮҰ [ 65] [ 66] [ 67] [ 68] [ 69] [ 70]

ж №ж“ҡеҚ°еәҰзҡ„з ”з©¶ж©ҹж§ӢиғҪжәҗз ”з©¶жүҖ [ 71]

еҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯйғЁй–Җзҡ„йӣ»еҠӣж¶ҲиҖ—жӯЈеңЁеўһеҠ пјҢеҺҹеӣ зӮәж–°иҫІдҪңзү©е“ҒзЁ®жңүжӣҙй«ҳзҡ„зҒҢжәүйңҖжұӮе’Ңж”ҝеәңжҸҗдҫӣзөҰиЈңиІјйӣ»еҠӣзҡ„зөҗжһңгҖӮеҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯйғЁй–Җж–ј2021-22иІЎеӢҷе№ҙеәҰдёӯжүҖеүөйҖ зҡ„еғ№еҖјдҪ”ж•ҙеҖӢеҚ°еәҰ經жҝҹзҡ„18.6%гҖӮиҖҢзӮәи©ІеңӢзҙ„45.5%зҡ„еӢһеӢ•еҠӣжҸҗдҫӣз”ҹиЁҲе’Ңе°ұжҘӯж©ҹжңғгҖӮ[ 71]

еҚ°еәҰж°ҙеҲ©зҒҢжәүзі»зөұеҢ…жӢ¬еҚ°еәҰжІіжөҒзҡ„дё»иҰҒе’Ңж¬ЎиҰҒдәәе·Ҙжё йҒ“з¶ІзөЎгҖҒж°ҙдә• зі»зөұпјҲең°дёӢж°ҙ пјүгҖҒе„Іж°ҙжұ е’Ңе…¶д»–йӣЁж°ҙ收йӣҶ й …зӣ®пјҢе…¶дёӯд»ҘжҠҪеҸ–ең°дёӢж°ҙзҡ„зі»зөұиҰҸжЁЎжңҖеӨ§гҖӮ[ 72] [ 73] еӯЈйўЁ её¶дҫҶзҡ„йҷҚж°ҙпјҲеҸғиҰӢйӣЁйӨҠиҫІжҘӯ [ 74] [ 75]

еҚ°еәҰеңЁйҒҺеҺ»50е№ҙе°ҮзҒҢжәүеҹәзӨҺиЁӯж–Ҫж”№е–„пјҢд№ҹж”№е–„зі§йЈҹе®үе…ЁгҖҒжёӣе°‘е°ҚеӯЈйўЁйҷҚж°ҙзҡ„дҫқиіҙгҖҒжҸҗй«ҳиҫІжҘӯз”ҹз”ўеҠӣдёҰеүөйҖ иҫІжқ‘е°ұжҘӯж©ҹжңғгҖӮз”Ёж–јзҒҢжәүиЁҲз•«иҖҢиҲҲе»әзҡ„ж°ҙеЈ©жңүеҠ©ж–јзӮәдёҚж–·еўһй•·зҡ„иҫІжқ‘дәәеҸЈжҸҗдҫӣйЈІз”Ёж°ҙгҖҒжҺ§еҲ¶жҙӘж°ҙдёҰйҳІжӯўд№ҫж—ұе°ҚиҫІжҘӯйҖ жҲҗзҡ„жҗҚе®ігҖӮ[ 76] [ 77] [ 78]

ж–јеҸӨеҗүжӢүзү№йӮҰзҡ„еҘіжҖ§иҫІжҘӯе·ҘдҪңиҖ…зҷјжҳҺдёҖзЁ®ж–°зҡ„пјҢзЁұзӮәеёғжҙӘж јйӯҜ ең°дёӢж°ҙиЈңзөҰ ж–№ејҸпјҢеңЁйӣЁеӯЈе°ҮеӨҡйӨҳзҡ„йҷҚж°ҙйҒҺжҝҫеҸҠе„Іе…Ҙең°дёӢж°ҙзі»зөұпјҢеҲ°д№ҫеӯЈжҷӮеҶҚжҠҪеҸ–еҲ©з”ЁгҖӮ[ 79]

жҲӘиҮі2011е№ҙпјҢеҚ°еәҰжңүеҖӢиҰҸжЁЎйҫҗеӨ§дё”еӨҡе…ғзҡ„иҫІжҘӯйғЁй–ҖпјҢе№іеқҮзҙ„дҪ”GDPзҡ„16%е’ҢеҮәеҸЈж”¶е…Ҙзҡ„10%гҖӮеҚ°еәҰзҡ„иҖ•ең°йқўз©ҚзӮә1,597,000е№іж–№е…¬йҮҢпјҲ3.946е„„иӢұз•қпјүпјҢдҪҚеұ…дё–з•Ң第дәҢпјҢеғ…ж¬Ўж–јзҫҺеңӢ гҖӮдә«жңүзҒҢжәүзҡ„иҫІең°йқўз©ҚзӮә826,000е№іж–№е…¬йҮҢпјҲ2.156е„„иӢұз•қпјүпјҢдҪҚеұ…дё–з•Ң第дёҖгҖӮеҚ°еәҰжҳҜе…ЁзҗғиЁұеӨҡиҫІдҪңзү©зҡ„дёүеӨ§з”ҹз”ўеңӢд№ӢдёҖпјҢеҢ…жӢ¬е°ҸйәҘгҖҒеӨ§зұігҖҒиұҶйЎһгҖҒжЈүиҠұгҖҒиҠұз”ҹ гҖҒж°ҙжһңе’Ң蔬иҸңгҖӮжҲӘиҮі2011е№ҙпјҢеҚ°еәҰж“Ғжңүдё–з•ҢдёҠж•ёзӣ®жңҖеӨҡзҡ„ж°ҙзүӣе’Ң家зүӣпјҢжҳҜжңҖеӨ§зҡ„зүӣеҘ¶з”ҹз”ўеңӢпјҢдё”ж“ҒжңүжңҖеӨ§е’ҢжҲҗй•·жңҖеҝ«зҡ„家зҰҪжҘӯд№ӢдёҖгҖӮ[ 80]

дёӢиЎЁжҢү經жҝҹеғ№еҖје°ҮеҚ°еәҰж–ј2009е№ҙжңҖйҮҚиҰҒзҡ„20зЁ®иҫІз”ўе“ҒеҲ—еҮәгҖӮзӮәйҖІиЎҢжҜ”ијғпјҢд№ҹе°Ү2010е№ҙе…Ёзҗғз”ҹз”ўеҠӣжңҖй«ҳиҫІең°зҡ„е№іеқҮз”ўйҮҸеҸҠе…¶жүҖеңЁеңӢ家зҡ„еҗҚзЁұеҲ—еҮәгҖӮж №ж“ҡиЎЁж јдёӯзҡ„ж•ёж“ҡпјҢеҚ°еәҰзҡ„иҫІжҘӯз”ҹз”ўйӮ„жңүеҫҲеӨ§зҡ„жҸҗеҚҮз©әй–“гҖӮеҰӮжһңиғҪеӨ жҸҗй«ҳиҫІжҘӯз”ҹз”ўж•ҲзҺҮпјҢеҚ°еәҰзҡ„иҫІжҘӯз”ўеҮәе’ҢиҫІж°‘зҡ„收е…ҘеқҮжңүеўһй•·зҡ„жҪӣеҠӣгҖӮ[ 81] [ 82]

дҫқз”ўеҖјжҺ’еәҸзҡ„еҚ°еәҰеүҚ20еҗҚиҫІз”ўе“Ғ[ 83] [ 84]

еҗҚж¬Ў

иҫІз”ўе“Ғ

з”ўеҖј (зҫҺе…ғ, 2016е№ҙ)

е–®дҪҚеғ№ж ј

е№іеқҮз”ўйҮҸ

з”ҹз”ўеҠӣжңҖй«ҳеңӢ家

1

еӨ§зұі

701.8е„„

0.27

3.85

9.82

жҫіеӨ§еҲ©дәһ

2

ж°ҙзүӣзүӣеҘ¶

430.9е„„

0.4

2.00[ 85]

2.00[ 85]

еҚ°еәҰ

3

д№ізүӣзүӣеҘ¶

325.5е„„

0.31

1.2[ 85]

10.3[ 85]

д»ҘиүІеҲ—

4

е°ҸйәҘ

260.6е„„

0.15

2.8

8.9

иҚ·иҳӯ

5

жЈүиҠұ (е°ҸжүҒиұҶ +жІ№зұҪ)

233.0е„„

1.43

1.6

4.6

д»ҘиүІеҲ—

6

иҠ’жһңпјҢз•ӘзҹіжҰҙ

145.2е„„

0.6

6.3

40.6

з¶ӯеҫ·и§’

7

蔬иҸң

118.7е„„

0.19

13.4

76.8

зҫҺеңӢ

8

йӣһиӮү

93.2е„„

0.64

10.6

20.2

иіҪжҷ®еӢ’ж–Ҝ

9

йҰ¬йҲҙи–Ҝ 82.3е„„

0.15

19.9

44.3

зҫҺеңӢ

10

йҰҷи•ү

81.3е„„

0.28

37.8

59.3

еҚ°е°ј

11

з”ҳи”—

74.4е„„

0.03

66

125

з§ҳйӯҜ

12

зҺүзұі

58.1е„„

0.42

1.1

5.5

е°јеҠ жӢүз“ң

13

ж©ҷ

56.2е„„

14

з•ӘиҢ„ 55.0е„„

0.37

19.3

55.9

дёӯеңӢ

15

й·№еҳҙиұҶ

5.4.0е„„

0.4

0.9

2.8

дёӯеңӢ

16

з§Ӣи‘ө

52.5е„„

0.35

7.6

23.9

д»ҘиүІеҲ—

17

еӨ§иұҶ

51.3е„„

0.26

1.1

3.7

еңҹиҖіе…¶

18

йӣһиӣӢ

46.4е„„

2.7

0.1[ 85]

0.42[ 85]

ж—Ҙжң¬

19

иҠұжӨ°иҸң иҲҮйқ’иҠұиҸң 43.3е„„

2.69

0.138[ 85]

0.424[ 85]

жі°еңӢ

20

жҙӢи”Ҙ 40.5е„„

0.21

16.6

67.3

ж„ӣзҲҫиҳӯ

ж №ж“ҡиҒҜеҗҲеңӢзі§иҫІзө„з№”дјҒжҘӯзөұиЁҲж•ёж“ҡеә« [ 86]

FAOSTATеҲҠеҮәзҡ„еҚ°еәҰиҫІз”ўж•ёж“ҡпјҲ2019е№ҙпјү

иҫІз”ўе“Ғ

з”ўеҖј

(е…¬еҷё)

иҳӢжһң

2,316,000

йҰҷи•ү

30,460,000

иұҶйЎһ

725,998

и…°жһң пјҲеё¶ж®јпјү

743,000

и“–йә»жІ№зұҪ

1,196,680

иҠұжӨ°иҸңиҲҮйқ’иҠұиҸң

9,083,000

ж«»жЎғ

11,107

й·№еҳҙиұҶ

9,937,990

иҫЈжӨ’иҲҮиғЎжӨ’пјҲд№ҫзҮҘпјү

1,743,000

иҫЈжӨ’иҲҮиғЎжӨ’пјҲж–°й®®пјү

81,837

жӨ°еӯҗ

14,682,000

е’–е•ЎиұҶпјҲж–°й®®пјү

319,500

й»ғз“ң иҲҮйҶғй»ғз“ң

199,018

и’ң

2,910,000

и–‘

1 788,000

и‘Ўиҗ„

3,041,000

жӘёжӘ¬ иҲҮиҗҠе§Ҷ

3,482,000

иҠ’жһң, еұұз«№ , з•ӘзҹіжҰҙ

25,631,000

иҘҝз“ңиҲҮе…¶д»– (еҢ…жӢ¬е“ҲеҜҶз“ң )

1,266,000

и•ҲйЎһ иҲҮжқҫйңІ

182,000

жңӘеҲ—еҗҚжІ№зұҪ

42,000

жҙӢи”ҘпјҲд№ҫзҮҘпјү

22,819,000

ж©ҷ

9,509,000

жңЁз“ң

6,050,000

жўЁ

300,000

йііжўЁ

1,711,000

йҰ¬йҲҙи–Ҝ

50,190,000

еӨ§зұі

177,645,000

еӨ§иұҶ

13,267,520

з”ҳи”—

405,416,180

з•Әи–Ҝ

1,156,000

иҢ¶и‘ү

1,390,080

иҸёи‘ү пјҲжңӘеҠ е·Ҙпјү

804,454

з•ӘиҢ„

19,007,000

иҘҝз“ң

2,495,000

е°ҸйәҘ

103,596,230

еҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯеңЁйҒҺеҺ»60е№ҙдёӯйҷӨзёҪз”ўйҮҸжңүеўһй•·еӨ–пјҢжҜҸе…¬й ғзҡ„е№іеқҮз”ўйҮҸд№ҹжңүеўһеҠ гҖӮдёӢиЎЁеҲ—еҮәжҹҗдәӣдҪңзү©еңЁ3е№ҙе…§зҡ„е№іеқҮз”ўйҮҸгҖӮеҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯз”ұж–јйҒ“и·Ҝе’Ңзҷјйӣ»иғҪеҠӣж”№е–„гҖҒзҹҘиӯҳзҙҜз©Қе’Ңж”№йқ©пјҢи®“з”ҹз”ўзҺҮеңЁ40е№ҙе…§жҸҗй«ҳ40%иҮі500%дёҚзӯүгҖӮ йӣ–然еҚ°еәҰеңЁиҫІжҘӯдёҠеҸ–еҫ—еӨ§е№…йҖІжӯҘпјҢдҪҶз”ўзҺҮд»Қеғ…зӮәе·Ій–ӢзҷјеңӢ家е’Ңжҹҗдәӣй–ӢзҷјдёӯеңӢ家дёӯиЎЁзҸҫжңҖдҪіиҫІең°зҡ„30% - 60%гҖӮжӯӨеӨ–пјҢйӣ–然已жңүжӯӨйЎһйҖІжӯҘпјҢдҪҶз”ұж–јеҹәзӨҺиЁӯж–Ҫи–„ејұе’Ңзө„з№”дёҚеҪ°зҡ„йӣ¶е”®зі»зөұпјҢ讓收穫еҫҢзҡ„дҪңзү©е№ізҷҪи…җж•—гҖҒжҗҚеӨұпјҢе°ҺиҮҙеҚ°еәҰзҡ„зі§йЈҹжҗҚеӨұзҺҮдҪҚеұ…дё–з•ҢеүҚзҹӣгҖӮ

еҚ°еәҰиҫІз”ўе“Ғз”ўйҮҸпјҢеҫһ1970е№ҙ-2010е№ҙжңҹй–“зҡ„жҜҸз•қз”ўзҺҮеўһй•· (е…¬ж–Ө/е…¬й ғ)

дҪңзү©[ 32]

е№іеқҮз”ўйҮҸ, 1970е№ҙвҖ“1971е№ҙ

е№іеқҮз”ўйҮҸ, 1990е№ҙвҖ“1991е№ҙ

е№іеқҮз”ўйҮҸ, 2010е№ҙвҖ“2011е№ҙ[ 87]

е№іеқҮз”ўйҮҸ, 2019е№ҙ[ 88]

еӨ§зұі

1123

1740

2240

4057.7

е°ҸйәҘ

1307

2281

2938

3533.4

иұҶйЎһ

524

578

689

441.3

жІ№зұҪ

579

771

1325

1592.8

з”ҳи”—

48322

65395

68596

80104.5

иҢ¶и‘ү

1182

1652

1669

2212.8

жЈүиҠұ

106

225

510

1156.6

еҗ„е№ҙз”ҹз”ўдёҚеҗҢдҪңзү©зҡ„иҫІең°йқўз©Қ (е–®дҪҚпјҡеҚғе…¬й ғ)[ 89]

дҪңзү©

1961е№ҙ

1971е№ҙ

1981е№ҙ

1991е№ҙ

2001е№ҙ

2011е№ҙ

еӨ§зұі

34694

34694

40708.4

42648.7

44900

44010

е°ҸйәҘ

12927

18240.5

22278.8

24167.1

25730.6

29068.6

иұҶйЎһ

3592

2582.8

2388

2123.1

1650

1700

жІ№зұҪ

486

453.3

557.5

557.5

716.7

1471

з”ҳи”—

2413

2615

2666.6

3686

4315.7

4944.39

иҢ¶и‘ү

331.229

358.675

384.242

421

504

600

жЈүиҠұ

7719

7800

8057.4

7661.4

9100

12178

ж №ж“ҡFAOжүҖзҷјдҪҲзҡ„2009е№ҙжңҖзөӮж•ёж“ҡе ұе‘ҠпјҢеҚ°еәҰжҳҜдёӢеҲ—иҫІз”ўе“Ғзҡ„жңҖеӨ§з”ҹз”ўеңӢпјҡ[ 90] [ 91]

ж №ж“ҡеҗҢдёҖд»ҪFAOе ұе‘ҠпјҢеҚ°еәҰжҳҜдёӢеҲ—иҫІз”ўе“Ғзҡ„第дәҢеӨ§з”ҹз”ўеңӢ:[ 90]

е°ҸйәҘ

еӨ§зұі

新鮮蔬иҸң

з”ҳи”—

иҠұз”ҹпјҲеё¶ж®јпјү

е°ҸжүҒиұҶ

и’ң

иҠұжӨ°иҸңиҲҮйқ’иҠұиҸң

иұҶйЎһпјҲж–°й®®пјү

иҠқйә»

и…°жһңпјҲеё¶ж®јпјү

и ¶з№ӯпјҲеҸҜжҠҪзөІпјү

зүӣеҘ¶пјҲе…Ёи„Ӯй®®еҘ¶пјү

иҢ¶и‘ү

йҰ¬йҲҙи–Ҝ

жҙӢи”Ҙ

жЈүзө®

жЈүзұҪ

иҢ„еӯҗ иӮүиұҶи”» , е°ҸиұҶи”» еұұзҫҠиӮү

й«ҳйә—иҸң иҲҮе…¶д»–и•“и–№еұ¬ еҚ—з“ң , еҚ—з“ңеұ¬

еҚ°еәҰж–ј2009е№ҙжҳҜдё–з•Ң第дёүеӨ§йӣһиӣӢгҖҒж©ҷгҖҒжӨ°еӯҗгҖҒз•ӘиҢ„гҖҒиұҢиұҶе’ҢиұҶйЎһз”ҹз”ўеңӢгҖӮ[ 90]

еҚ°еәҰе’ҢдёӯеңӢжӯЈеңЁз«¶зӣёеүөйҖ ж°ҙзЁ»з”ўйҮҸзҡ„дё–з•ҢзҙҖйҢ„гҖӮ дёӯеңӢеңӢ家йӣңдәӨж°ҙзЁ»е·ҘзЁӢжҠҖиЎ“з ”з©¶дёӯеҝғпјҲChina National Hybrid Rice Research and Development Centreпјүзҡ„иўҒйҡҶе№і ж–ј2010е№ҙеңЁзӨәзҜ„з”°еүөйҖ еҮәжҜҸе…¬й ғ19еҷёж°ҙзЁ»е–®з”ўзҡ„дё–з•ҢзҙҖйҢ„гҖӮ 2011е№ҙпјҢеҚ°еәҰиҫІж°‘иҳҮжӣјзү№В·еә«йҰ¬зҲҫ (Sumant Kumar) жү“з ҙйҖҷдёҖиЁҳйҢ„пјҢд»–еңЁжҜ”е“ҲзҲҫйӮҰзҡ„дёҖзӨәзҜ„еҚҖз”ҹз”ўеҮәжҜҸе…¬й ғ22.4еҷёзҡ„ж•ёйҮҸгҖӮеә«йҰ¬зҲҫиҒІзЁұд»–жҳҜжҺЎз”Ёж–°й–Ӣзҷјзҡ„ж°ҙзЁ»е“ҒзЁ®е’Ңж°ҙзЁ»йӣҶзҙ„еҢ–зі»зөұпјҲSRIпјү(дёҖзЁ®иҫІжҘӯеүөж–°)дҫҶйҒ”жҲҗгҖӮдёӯеңӢе’ҢеҚ°еәҰзҡ„й«ҳз”ўйҮҸзҙҖйҢ„д»ҚйңҖ經йҒҺжӣҙеҡҙ謹зҡ„й©—иӯү - еҢ…жӢ¬еңЁ7е…¬й ғзҡ„иҫІз”°дёҠйҖІиЎҢеӨ§иҰҸжЁЎзЁ®жӨҚпјҢдёҰйҖЈзәҢе…©е№ҙз”ўеҮәзӣёеҗҢзҡ„з”ўйҮҸгҖӮ[ 92] [ 93] [ 94] [ 95]

еҚ°еәҰж°ҙжһңгҖҒ蔬иҸңе’Ңе …жһңзӯүең’и—қз”ўе“Ғзҡ„зёҪз”ўйҮҸе’Ң經жҝҹеғ№еҖјеңЁ2002е№ҙиҮі2012е№ҙзҡ„10е№ҙжңҹй–“еўһеҠ дёҖеҖҚгҖӮ еҚ°еәҰзҡ„2013е№ҙең’и—қзёҪз”ўйҮҸйҒ”2.774е„„еҷёпјҢжҳҜеғ…ж¬Ўж–јдёӯеңӢзҡ„第дәҢеӨ§ең’и—қз”ўе“Ғз”ҹз”ўеңӢгҖӮ[ 96] еҸҜеҸҜиұҶ гҖҒжӨ°еӯҗзӯүпјүгҖҒ100иҗ¬еҷёиҠійҰҷең’и—қиҫІз”ўе“Ғе’Ң170иҗ¬еҷёй®®иҠұпјҲ76е„„жңөеҲҮиҠұ пјүгҖӮ[ 97] [ 98]

еҚ°еәҰж–ј2013е№ҙзҡ„ең’и—қз”ўе“Ғж•ёйҮҸиҲҮе…¶д»–3еңӢжҜ”ијғ

еңӢеҗҚ[ 99]

ж°ҙжһңз”ўең°йқўз©Қ[ 99]

е№іеқҮз”ўйҮҸ[ 99]

蔬иҸңз”ўең°йқўз©Қ[ 99]

е№іеқҮз”ўйҮҸ[ 99]

еҚ°еәҰ 7.0

11.6

9.2

52.36

дёӯеңӢ 11.8

11.6

24.6

23.4

иҘҝзҸӯзүҷ 1.54

9.1

0.32

39.3

зҫҺеӣҪ 1.14

23.3

1.1

32.5

дё–з•Ң

57.3

11.3

60.0

19.7

еҚ°еәҰж–ј2013иІЎж”ҝе№ҙеәҰзҡ„ең’и—қз”ўе“ҒеҮәеҸЈйЎҚйҒ”1,436.5е„„еҚ°еәҰзӣ§жҜ”пјҲ17е„„зҫҺе…ғпјүпјҢжҺҘиҝ‘2010е№ҙеҮәеҸЈйЎҚзҡ„е…©еҖҚгҖӮ[ 96]

еҚ°еәҰиҮӘеҸӨд»ҘдҫҶеҚіжңүжңүж©ҹиҫІжҘӯпјҢдё”еҶҚж¬ЎжҲҗзӮәи©ІеңӢжҢҒзәҢеўһй•·зҡ„йғЁй–ҖгҖӮжңүж©ҹз”ҹз”ўиғҪжҸҗдҫӣжё…жҪ”гҖҒз¶ иүІзҡ„з”ҹз”ўж–№жі•пјҢдёҚдҪҝз”ЁеҗҲжҲҗиӮҘж–ҷе’ҢиҫІи—ҘпјҢдёҰдё”иғҪеңЁеёӮе ҙдёҠеҸ–еҫ—ијғй«ҳзҡ„е”®еғ№гҖӮеҚ°еәҰжңү65иҗ¬е®¶жңүж©ҹз”ҹз”ўиҖ…пјҢжҜ”е…¶д»–еңӢ家зӮәеӨҡгҖӮ[ 100] иҠ¬иҳӯ е’Ңе°ҡжҜ”дәһ пјүгҖӮ[ 101] з”ҹзү©зҮғж°Ј /з”Ізғ· /еӨ©з„¶ж°Ј е’Ңе°‘йҮҸзҡ„ж°ҙд»Ҙжңүж©ҹж–№ејҸеҹ№йӨҠз”ІеҹәзҗғиҸҢ [ 102] [ 103] [ 104] [ 105]

еңЁйҰ¬е“ҲжӢүд»Җзү№жӢүйӮҰзҡ„з”°йҮҺдёӯйҒӢијёжҺЎж”¶з”ҳи”—зҡ„и»ҠијӣгҖӮ еҚ°еәҰиҮӘ1947е№ҙи„«йӣўиӢұеңӢ зҚЁз«Ӣд»ҘдҫҶпјҢеҗҲдҪңзӨҫзҡ„ж•ёйҮҸеӨ§е№…жҲҗй•·пјҢдё»иҰҒжҳҜеңЁиҫІжҘӯй ҳеҹҹгҖӮи©ІеңӢеңЁең°ж–№гҖҒеҚҖеҹҹгҖҒйӮҰе’ҢеңӢ家еұӨзҙҡж“ҒжңүеҚ”еҠ©иҫІз”ўе“ҒиЎҢйҠ·зҡ„еҗҲдҪңзӨҫз¶ІзөЎгҖӮдё»иҰҒиҷ•зҗҶзҡ„е•Ҷе“ҒжҳҜзі§йЈҹгҖҒй»ғйә»гҖҒжЈүиҠұгҖҒзі–гҖҒзүӣеҘ¶гҖҒж°ҙжһңе’Ңе …жһңгҖӮ[ 106] [ 107]

еҚ°еәҰеӨ§йғЁеҲҶзҡ„йЈҹзі–з”ҹз”ўзҡҶеңЁз•¶ең°еҗҲдҪңзӨҫж“Ғжңүзҡ„е·Ҙе» дёӯйҖІиЎҢгҖӮ[ 78] [ 108] [ 109] еңӢеӨ§й»Ё зҡ„еҸғж”ҝиҖ…иҲҮ當ең°зҡ„зі–жҘӯеҗҲдҪңзӨҫжңүиҒҜ繫пјҢдёҰеңЁзі–е» е’Ң當ең°ж”ҝжІ»д№Ӣй–“е»әз«Ӣе…ұз”ҹй—ңдҝӮгҖӮ[ 110] [ 111] [ 107]

еҗҲдҪңзӨҫеңЁеҚ°еәҰж°ҙжһңе’Ң蔬иҸңзҡ„ж•ҙй«”иЎҢйҠ·дёӯе…·жңүйҮҚиҰҒзҡ„дҪңз”ЁпјҢиҲҮзі–жҘӯзӣёеҗҢгҖӮеҗҲдҪңзӨҫиҷ•зҗҶзҡ„иҫІз”ўе“Ғж•ёйҮҸиҮӘ1980е№ҙд»Јй–Ӣе§Ӣе‘ҲжҢҮж•ёзҙҡеўһй•·гҖӮйҖҷдәӣеҗҲдҪңзӨҫйҠ·е”®зҡ„еёёиҰӢж°ҙжһңе’Ң蔬иҸңжңүйҰҷи•үгҖҒиҠ’жһңгҖҒи‘Ўиҗ„гҖҒжҙӢи”ҘзӯүгҖӮ[ 112]

ж–је“ҲйҮҢдәһзҙҚйӮҰжі•йҮҢйҒ”е·ҙеҫ· зҡ„е·ҙзҙҚж–Ҝд№іе“Ғ иө·жәҗж–јеҸӨеҗүжӢүзү№йӮҰзҡ„йҳҝз©ҶзҲҫ [ 113]

еҗҲдҪңзӨҫеңЁеҚ°еәҰиҫІжқ‘ең°еҚҖжҸҗдҫӣдҝЎиІёиһҚиіҮж–№йқўе…·жңүйҮҚиҰҒдҪңз”ЁгҖӮйҖҷдәӣж©ҹж§Ӣзі–жҘӯеҗҲдҪңзӨҫйЎһдјјпјҢжҳҜ當ең°ж”ҝжІ»дәәзү©зҡ„ж¬ҠеҠӣеҹәзӨҺгҖӮ[ 107]

ж–ј2003-2005е№ҙжңҹй–“зҡ„еҚ°еәҰеҗ„еҚҖиҫІжҘӯз”ҹз”ўеҠӣгҖӮеңЁдёҚеҗҢең°еҚҖзҡ„з”ҹз”ўеҠӣжңүеҫҲеӨ§зҡ„е·®з•°гҖӮ еңЁеҫ·йҮҢеҗҚзӮәе“ҲйҮҢВ·й®‘еҲ© еҚ°еәҰзјәд№ҸеҶ·и—ҸиЁӯж–ҪгҖҒйҒ©з•¶еҢ…иЈқе’Ңе®үе…Ёй«ҳж•Ҳзҡ„йҒӢијёзі»зөұпјҢе…¶йЈҹе“ҒжҗҚиҖ—зҺҮеңЁе…ЁзҗғеҗҚеҲ—еүҚиҢ…пјҢзү№еҲҘжҳҜеҮәзҸҫеңЁеӯЈйўЁе’Ңе…¶д»–жғЎеҠЈеӨ©ж°Јжңҹй–“гҖӮ當ең°ж¶ҲиІ»иҖ…йҖҡеёёеңЁйғҠеҚҖеёӮе ҙпјҲеҰӮең–жүҖзӨәпјүжҲ–и·ҜйӮҠж”ӨиІ©иіјиІ·иҫІз”ўе“ҒгҖӮ еңЁеҚ°еәҰзҡ„дёҖдәӣең°еҚҖд»ҚжҺЎз”ЁеӮізөұзҡ„зүӣиҖ•ж–№ејҸпјҢйҖҷйЎһиҫІжі•зҡ„дәәеқҮз”ҹз”ўеҠӣе’ҢиҫІж°‘收е…ҘеқҮиҷ•ж–јдҪҺдёӢж°ҙе№ігҖӮ еҚ°еәҰеҫһ2002е№ҙй–Ӣе§Ӣе·ІжҲҗзӮәе…ЁзҗғжңҖеӨ§зҡ„жӣіеј•ж©ҹ иЈҪйҖ еңӢпјҢж–ј2013е№ҙзҡ„з”ўйҮҸдҪ”е…Ёзҗғзҡ„29%гҖӮеҚ°еәҰжң¬иә«д№ҹжҳҜе…ЁзҗғжңҖеӨ§зҡ„жӣіеј•ж©ҹеёӮе ҙгҖӮ[ 114] [ 115] йӣ·з“ҰйҮҢ "еҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯзҷјеұ•еҒңж»ҜдёҚеүҚпјҢе·ІжҲҗзӮәеңӢ家зҷјеұ•зҡ„жІүйҮҚиІ ж“”гҖӮ йҡЁи‘—дәәеҸЈжҢҒзәҢеўһй•·пјҢе°Қзі§йЈҹзҡ„йңҖжұӮж—ҘзӣҠж®·еҲҮпјҢиҖҢиҗҪеҫҢзҡ„иҫІжҘӯз”ҹз”ўж–№ејҸеҚ»з„Ўжі•ж»ҝи¶ійҖҷдёҖйңҖжұӮгҖӮзҒҢжәүзі»зөұеӨұдҝ®гҖҒиҫІж°‘зјәд№ҸзҸҫд»ЈеҢ–иҫІжҘӯзҹҘиӯҳзӯүе•ҸйЎҢпјҢдҪҝеҫ—еҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯйқўиҮЁеҡҙеі»жҢ‘жҲ°гҖӮжӯӨеӨ–пјҢеёӮе ҙйҖҡи·ҜдёҚжҡўгҖҒиҫІз”ўе“Ғеғ№ж јдёҚз©©е®ҡзӯүеӣ зҙ пјҢд№ҹеҡҙйҮҚеҪұйҹҝиҫІж°‘зҡ„收е…ҘгҖӮ"

"еҚ°еәҰжҳҜе…ЁзҗғжңҖеӨ§зҡ„ж°‘дё»еңӢ家пјҢе…¶13е„„зҡ„дәәеҸЈиҳҠи—Ҹжңүе·ЁеӨ§зҡ„зҷјеұ•жҪӣеҠӣгҖӮи©ІеңӢзҡ„經жҝҹеңЁиҝ‘10е№ҙдҫҶй«ҳйҖҹжҲҗй•·пјҢиәҚеҚҮзӮәдё–з•Ң第4еӨ§з¶“жҝҹй«”пјҢеңЁе…ЁзҗғиҲһеҸ°дёҠжү®жј”ж—ҘзӣҠйҮҚиҰҒзҡ„и§’иүІгҖӮиҖҢеҗҢжҷӮеҚ°еәҰеңЁеҜҰзҸҫиҒҜеҗҲеңӢеҚғе№ҙзҷјеұ•зӣ®жЁҷ ж–№йқўд№ҹеҸ–еҫ—йЎҜи‘—йҖІеұ•гҖӮ然иҖҢзҷјеұ•дёҚеқҮиЎЎд»ҚжҳҜеҚ°еәҰйқўиҮЁзҡ„жҢ‘жҲ°пјҢеҲқжӯҘиЁҲз®—и©ІеңӢеңЁ2009-10е№ҙзҡ„иІ§зӘ®зҺҮзӮә32%пјҢијғ2004-05е№ҙзҡ„37%з•ҘжңүйҖІжӯҘгҖӮиІ§еҜҢе·®и·қзҡ„ж“ҙеӨ§йңҖиҰҒй«ҳеәҰй—ңжіЁгҖӮеҚ°еәҰж–јжңӘдҫҶжҮүжҢҒзәҢжҺЁеӢ•иҫІжҘӯзҸҫд»ЈеҢ–пјҢдҝғйҖІиҫІжқ‘經жҝҹеӨҡе…ғеҢ–пјҢд»ҘеҜҰзҸҫжӣҙеқҮиЎЎзҡ„зҷјеұ•гҖӮ

вҖ”вҖ”дё–з•ҢйҠҖиЎҢпјҡ"гҖҠ2011е№ҙеҚ°еәҰеңӢ家жҰӮжіҒгҖӢ"[ 23] FAOж–ј2003е№ҙзҷјиЎЁзҡ„е ұе‘ҠпјҢе°ҚеҚ°еәҰ1970е№ҙиҮі2001е№ҙзҡ„иҫІжҘӯжҲҗй•·йҖІиЎҢеҲҶжһҗпјҢжҢҮеҮәеҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯеӯҳеңЁзі»зөұжҖ§е•ҸйЎҢгҖӮе°Қж–јдё»йЈҹпјҢ1970-76е№ҙгҖҒ1976-82е№ҙгҖҒ1982-88е№ҙгҖҒ1988-194е№ҙгҖҒ1994-2000е№ҙйҖҷ6ж®өжңҹй–“зҡ„з”ўйҮҸе№ҙеўһй•·зҺҮеҲҶеҲҘзӮә2.5%гҖҒ2.5%гҖҒ3.0%гҖҒ2.6%е’Ң1.8%гҖӮиҫІжҘӯзёҪз”ўеҖјжҢҮж•ёзҡ„зӣёжҮүеҲҶжһҗд№ҹйЎҜзӨәйЎһдјјзҡ„иҰҸеҫӢпјҢ1994-2000е№ҙзҡ„жҲҗй•·зҺҮеғ…зӮәжҜҸе№ҙ1.5%гҖӮ[ 117]

иҫІж°‘йқўиҮЁзҡ„жңҖеӨ§е•ҸйЎҢжҳҜиҫІз”ўе“Ғеғ№ж јдҪҺгҖӮжңҖиҝ‘зҡ„дёҖй …з ”з©¶е ұе‘ҠйЎҜзӨәеҹәж–јз”ҹз”ўжүҖйңҖиғҪжәҗзҡ„йҒ©з•¶е®ҡеғ№дёҰе°ҮиҫІжҘӯе·ҘиіҮиҲҮе·ҘжҘӯе·ҘиіҮжӢүе№іпјҢе°ҮеҸҜиғҪе°ҚиҫІж°‘жңүеҲ©гҖӮ[ 118]

еҚ°еәҰзҡ„иҫІжқ‘йҒ“и·Ҝе»әиЁӯеҡҙйҮҚдёҚи¶іпјҢеҪұйҹҝеҺҹж–ҷзҡ„зҡ„ијёе…ҘеҸҠиҫІз”ўзҡ„еҸҠжҷӮијёеҮәпјҢзҒҢжәүзі»зөұдёҚи¶іпјҢе°ҺиҮҙйғЁеҲҶең°еҚҖеӣ зјәж°ҙиҖҢиҮҙжӯү收гҖӮиҖҢеңЁжңүдәӣең°еҚҖпјҢеӣ жңүжҙӘж°ҙгҖҒзЁ®еӯҗе“ҒиіӘдёҚиүҜе’ҢиҖ•дҪңж•ҲзҺҮдҪҺдёӢгҖҒзјәд№ҸеҶ·и—ҸиЁӯж–Ҫе’Ң收жҲҗзү©и…җж•—пјҢе°ҺиҮҙи¶…йҒҺ30%зҡ„иҫІз”ўе“Ғеҝ…й ҲжЈ„зҪ®пјҢзјәд№Ҹжңүзө„з№”зҡ„йӣ¶е”®зі»зөұеҸҠ具競зҲӯжҖ§зҡ„買家пјҢиҖҢйҷҗеҲ¶иҫІж°‘еҮәе”®еү©йӨҳз”ўе“Ғе’Ң經жҝҹдҪңзү©зҡ„иғҪеҠӣгҖӮе°Қж–јеҗҢдёҖиҫІз”ўе“Ғзҡ„йӣ¶е”®еғ№ж јпјҢеҚ°еәҰиҫІж°‘еҸӘеҫ—еҲ°ж¶ҲиІ»иҖ…ж”Ҝд»ҳеғ№ж јзҡ„10%еҲ°23%пјҢдёӯй–“зҡ„е·®еғ№жҳҜз”ўе“Ғи…җзҲӣжҗҚеӨұгҖҒиЎҢйҠ·ж•ҲзҺҮдёҚеҪ°е’Ңдёӯй–“е•Ҷзҡ„еҲ©жҪӨгҖӮиҖҢеңЁе·Ій–Ӣзҷјзҡ„經жҝҹй«”еҰӮжӯҗжҙІе’ҢзҫҺеңӢпјҢиҫІж°‘зҚІеҫ—зҡ„жҳҜйӣ¶е”®еғ№ж јзҡ„64%иҮі81%гҖӮ[ 119]

йӣ–然еҚ°еәҰе·ІеҜҰзҸҫдё»йЈҹиҮӘзөҰиҮӘи¶іпјҢдҪҶе…¶иҫІжҘӯз”ҹз”ўеҠӣд»ҚдҪҺж–је·ҙиҘҝгҖҒзҫҺеңӢгҖҒжі•еңӢ зӯүеңӢгҖӮдҫӢеҰӮеҚ°еәҰе°ҸйәҘиҫІең°жҜҸе№ҙжҜҸе…¬й ғзҡ„з”ўйҮҸзҙ„зӮәжі•еңӢиҫІең°зҡ„дёүеҲҶд№ӢдёҖгҖӮеҚ°еәҰзҡ„еӨ§зұіз”ҹз”ўеҠӣйӮ„дёҚеҲ°дёӯеңӢзҡ„дёҖеҚҠгҖӮ[ 120]

еҚ°еәҰе…¶д»–дё»йЈҹзҡ„з”ҹз”ўеҠӣд№ҹеҗҢжЁЈијғдҪҺгҖӮеҚ°еәҰе…ЁиҰҒзҙ з”ҹз”ўзҺҮ пјҲжҠҖиЎ“йҖІжӯҘзҺҮпјүе№ҙеўһзҺҮд»ҚдҪҺж–ј2%пјҢзӣёијғд№ӢдёӢпјҢдёӯеңӢзҡ„е…ЁиҰҒзҙ з”ҹз”ўзҺҮжҜҸе№ҙжҲҗй•·зҙ„6%пјҢиҖҢдё”дёӯеңӢд№ҹжңүеӨ§йҮҸе°ҸиҫІгҖӮ

зӣёијғд№ӢдёӢпјҢеҚ°еәҰжңүдәӣең°еҚҖзҡ„з”ҳи”—гҖҒжңЁи–Ҝ е’ҢиҢ¶дҪңзү©зҡ„жңүе…ЁзҗғжңҖй«ҳзҡ„з”ўйҮҸгҖӮ[ 121]

еҚ°еәҰеҗ„йӮҰй–“зҡ„иҫІдҪңзү©з”ўйҮҸе·®з•°еӨ§гҖӮдёҖдәӣйӮҰжҜҸе–®дҪҚйқўз©Қзҡ„зі§йЈҹз”ўйҮҸжҳҜе…¶д»–йӮҰзҡ„е…©еҲ°дёүеҖҚгҖӮ

еҰӮең–жүҖзӨәпјҢеҚ°еәҰеӮізөұиҫІжҘӯз”ҹз”ўеҠӣй«ҳзҡ„ең°еҚҖжҳҜеңЁиҘҝеҢ—йғЁпјҲж—ҒйҒ®жҷ®йӮҰгҖҒе“ҲйҮҢдәһзҙҚйӮҰе’ҢеҢ—ж–№йӮҰиҘҝйғЁпјүгҖҒеҚ°еәҰж¬ЎеӨ§йҷё е…©еІёжІҝжө·ең°еҚҖгҖҒиҘҝеӯҹеҠ жӢүйӮҰе’ҢеқҰзұізҲҫйӮЈйғҪйӮҰгҖӮиҝ‘е№ҙдҫҶпјҢеҚ°еәҰдёӯйғЁзҡ„дёӯеӨ®йӮҰгҖҒиіҲеқҺеҫ·йӮҰ гҖҒжҒ°и’Ӯж–ҜеҠ зҲҫйӮҰ е’ҢиҘҝйғЁзҡ„еҸӨеҗүжӢүзү№йӮҰзҡ„иҫІжҘӯзҷјеұ•иҝ…йҖҹгҖӮ[ 122]

дёӢиЎЁе°Ү2001е№ҙиҮі2002е№ҙеҚ°еәҰдёүеҖӢйӮҰпјҢе№ҫзЁ®дё»иҰҒиҫІдҪңзү©зҡ„е№іеқҮе–®дҪҚйқўз©Қз”ўйҮҸеҲ—еҮәпјҢд»ҘдҫӣеҸғиҖғгҖӮ[ 123]

Crop[ 123]

жҜ”е“ҲзҲҫйӮҰиҫІең°е№іеқҮз”ўйҮҸ

еҚЎзҙҚеЎ”еҚЎйӮҰиҫІең°е№іеқҮз”ўйҮҸ

ж—ҒйҒ®жҷ®йӮҰиҫІең°е№іеқҮз”ўйҮҸ

е…¬ж–Ө/е…¬й ғ

е…¬ж–Ө/е…¬й ғ

е…¬ж–Ө/е…¬й ғ

е°ҸйәҘ

2020

жңӘзҹҘ

3880

еӨ§зұі

1370

2380

3130

иұҶйЎһ

610

470

820

жІ№зұҪ

620

680

1200

з”ҳи”—

45510

79560

65300

еҚ°еәҰжңүдәӣиҫІең°зҡ„иҫІдҪңзү©з”ўйҮҸеғ…зӣёз•¶ж–јзҫҺеңӢе’Ңжӯҗзӣҹзӯүе·Ій–ӢзҷјеңӢ家иҫІе ҙжңҖй«ҳз”ўйҮҸзҡ„90%д»Ҙе…§гҖӮеҚ°еәҰжІ’д»»дёҖйӮҰеңЁжҜҸзЁ®дҪңзү©зҡ„з”ўйҮҸеқҮжҺ’еҗҚ第дёҖгҖӮеқҰзұізҲҫйӮЈйғҪйӮҰзҡ„ж°ҙзЁ»е’Ңз”ҳи”—з”ўйҮҸжңҖй«ҳпјҢе“ҲйҮҢдәһзҙҚйӮҰзҡ„е°ҸйәҘе’ҢзІ—зі§з”ўйҮҸжңҖй«ҳпјҢеҚЎзҙҚеЎ”е…ӢйӮҰзҡ„жЈүиҠұз”ўйҮҸжңҖй«ҳпјҢжҜ”е“ҲзҲҫйӮҰзҡ„иұҶйЎһз”ўйҮҸжңҖй«ҳпјҢиҖҢе…¶д»–йӮҰеүҮеңЁең’и—қгҖҒж°ҙз”ўйӨҠж®–гҖҒиҠұеҚүе’Ңж°ҙжһңзЁ®жӨҚж–№йқўиЎЁзҸҫе„Әз•°гҖӮжӯӨйЎһз”ҹз”ўеҠӣзҡ„е·®з•°жҳҜ當ең°еҹәзӨҺиЁӯж–ҪгҖҒеңҹеЈӨе“ҒиіӘгҖҒеҫ®ж°ЈеҖҷгҖҒ當ең°иіҮжәҗгҖҒиҫІж°‘зҹҘиӯҳе’Ңеүөж–°зҡ„з¶ңеҗҲзөҗжһңгҖӮ[ 123]

еҚ°еәҰзҡ„йЈҹзү©еҲҶй…Қзі»зөұж•ҲзҺҮжҘөдҪҺгҖӮиҫІз”ўе“Ғзҡ„жөҒеӢ•еҸ—еҲ°еҡҙж јзӣЈз®ЎпјҢе°ҚиҫІз”ўе“Ғзҡ„зҮҹйҠ·е’ҢжөҒеӢ•еӯҳеңЁйӮҰйҡӣз”ҡиҮіең°еҚҖй–“зҡ„йҷҗеҲ¶гҖӮ[ 123]

дёҖй …з ”з©¶е ұе‘ҠиЎЁзӨәеҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯж”ҝзӯ–жҮүйҮҚй»һй—ңжіЁж”№е–„иҫІжқ‘еҹәзӨҺиЁӯж–ҪпјҢдё»иҰҒжҳҜеңЁзҒҢжәүе’ҢйҳІжҙӘд»ҘеҸҠй«ҳз”ўйҮҸе’ҢжҠ—з—…е“ҒзЁ®зҹҘиӯҳзҡ„еӮіж’ӯгҖӮжӯӨеӨ–йҖҸйҒҺеҶ·и—ҸгҖҒиЎӣз”ҹеҢ…иЈқе’Ңй«ҳж•Ҳзҡ„йӣ¶е”®жЁЎејҸеҸҜйҷҚдҪҺжөӘиІ»пјҢиҖҢжҸҗй«ҳз”ўеҮәе’ҢеўһеҠ 收е…ҘгҖӮ[ 123]

е°ҺиҮҙеҚ°еәҰз”ҹз”ўзҺҮдҪҺдёӢзҡ„еҺҹеӣ еҰӮдёӢпјҡ

иҫІжҲ¶ж“Ғжңүзҡ„е№іеқҮиҫІең°йқўз©Қйқһеёёе°ҸпјҲдёҚеҲ°2е…¬й ғпјүпјҢдёҰдё”з”ұж–јж“Ғжңүеңҹең°дёҠйҷҗжі•жЎҲд»ҘеҸҠеңЁжҹҗдәӣжғ…жіҒдёӢзҡ„家еәӯзіҫзҙӣиҖҢе°ҺиҮҙиҫІең°еҮәзҸҫзўҺзүҮеҢ–зҸҫиұЎгҖӮйҖҷйЎһе°ҸиҫІең°еҫҖеҫҖдәәжүӢйҒҺеү©пјҢеҪўжҲҗи®ҠзӣёеӨұжҘӯе’Ңз”ҹз”ўеҠӣдҪҺдёӢгҖӮдёҖдәӣе ұе‘ҠиҒІзЁұе°ҸиҫІеҸҜиғҪдёҚжҳҜз”ҹз”ўеҠӣдҪҺдёӢзҡ„еҺҹеӣ пјҢдҫӢеҰӮдёӯеңӢзҡ„е°ҸиҫІдҪ”е…¶иҫІжҘӯдәәеҸЈзҡ„97%д»ҘдёҠпјҢ[ 124]

зӣёијғж–јз¶ иүІйқ©е‘ҪжүҖеё¶дҫҶзҡ„йЎҜи‘—жҲҗжһңпјҢзҸҫд»ЈиҫІжҘӯжҠҖиЎ“зҡ„жҺЁе»Јд»ҚйқўиҮЁи«ёеӨҡжҢ‘жҲ°гҖӮ иҫІж°‘е°Қж–°жҠҖиЎ“зҡ„иӘҚзҹҘдёҚи¶ігҖҒй«ҳжҳӮзҡ„жҠ•е…ҘжҲҗжң¬д»ҘеҸҠе°ҸиҫІжҲ¶зҡ„еҜҰйҡӣж“ҚдҪңеӣ°йӣЈпјҢйғҪйҷҗеҲ¶зҸҫд»ЈиҫІжҘӯзҡ„зҷјеұ•гҖӮ

ж №ж“ҡдё–з•ҢйҠҖиЎҢеҚ°еәҰеҲҶиЎҢзҷјиЎЁзҡ„гҖҠиҫІжҘӯе’ҢиҫІжқ‘зҷјеұ•е„Әе…ҲдәӢй …гҖӢпјҢеҚ°еәҰзҡ„еӨ§йҮҸиҫІжҘӯиЈңиІјеҸҚиҖҢжҳҜйҳ»зӨҷеңЁжҸҗе‘Ҡз”ҹз”ўеҠӣж–№йқўзҡ„жҠ•иіҮгҖӮйҖҷй …и©•дј°дё»иҰҒеҹәж–јз”ҹз”ўеҠӣзҡ„иЎЎйҮҸпјҢдёҰжңӘе°Үд»»дҪ•з”ҹж…ӢеҪұйҹҝеҲ—е…ҘиҖғж…®гҖӮж №ж“ҡж–°иҮӘз”ұдё»зҫ©и§Җй»һпјҢз”ұж–јж”ҝеәңе№Ій җеӢһеӢ•еҠӣгҖҒеңҹең°е’ҢдҝЎиІёеёӮе ҙпјҢе°ҚиҫІжҘӯзҡ„йҒҺеәҰзӣЈз®ЎеҸҚиҖҢе°ҮжҲҗжң¬гҖҒеғ№ж јйўЁйҡӘе’ҢдёҚзўәе®ҡжҖ§еўһй«ҳгҖӮеҚ°еәҰеӯҳеңЁеҹәзӨҺиЁӯж–Ҫе’ҢжңҚеӢҷдёҚи¶ізҡ„е•ҸйЎҢгҖӮ[ 125] [ 125] [ 126] иҒҜеҗҲеңӢ ж”ҝеәңй–“ж°ЈеҖҷи®ҠеҢ–е°Ҳй–Җ委員жңғ пјҲIPCCпјүзҷјдҪҲе ұе‘ҠзЁұпјҢ2030е№ҙеҫҢзі§йЈҹе®үе…ЁеҸҜиғҪжңғжҲҗзӮәеҚ°еәҰзҡ„дёҖеӨ§е•ҸйЎҢгҖӮ[ 127]

ж–ҮзӣІе……ж–ҘгҖҒзӨҫжңғ經жҝҹиҗҪеҫҢгҖҒеңҹең°ж”№йқ©йҖІеұ•з·©ж…ўгҖҒиҫІз”ўе“ҒйҮ‘иһҚе’ҢиЎҢйҠ·жңҚеӢҷдёҚи¶іжҲ–ж•ҲзҺҮдҪҺдёӢгҖӮ

ж”ҝеәңж”ҝзӯ–дёҚдёҖгҖӮиҫІжҘӯиЈңиІје’Ң稅收常жңғеӣ зҹӯжңҹж”ҝжІ»зӣ®зҡ„пјҢиҖҢеңЁжІ’дәӢеүҚйҖҡзҹҘзҡ„жғ…жіҒдёӢеҚіж”№и®ҠгҖӮ

зҒҢжәүиЁӯж–ҪдёҚи¶іпјҢ2003-04иІЎж”ҝе№ҙеәҰеҸӘжңү52.6%зҡ„иҫІең°еҸ–еҫ—зҒҢжәүпјҢ[ 128] [ 129] еҚ°еәҰеңӢ家иҫІжҘӯиҲҮй„үжқ‘зҷјеұ•йҠҖиЎҢ [ 130] [ 131] [ 132]

з”ұж–јиҫІз”ўе“ҒдҫӣжҮүйҸҲж•ҲзҺҮдҪҺдёӢпјҢжүҖжңүйЈҹе“ҒдёӯжңүдёүеҲҶд№ӢдёҖи…җзҲӣпјҢиҖҢж”ҝеәңжғійҖҸйҒҺжІғзҲҫз‘ӘеҢ– [ 133]

еҚ°еәҰеңӢ家зҠҜзҪӘиЁҳйҢ„еұҖ [ 134] [ 134] [ 135] [ 136] [ 137] [ 138]

еҚ°еәҰзҡ„иҫІз”ўе“ҒиЎҢйҠ·зі»зөұз”ҡзӮәиҗҪеҫҢгҖӮ[ 139]

еҚ°еәҰж–ј2007е№ҙзҷјдҪҲзҡ„еңӢ家иҫІж°‘ж”ҝзӯ–[ 140] [ 140]

зҚІеҫ—и«ҫиІқзҲҫ經жҝҹеӯёзҚҺ зҡ„зҰҸеҲ©з¶“жҝҹеӯё 家йҳҝйҰ¬и’ӮдәһВ·жЈ® жҸҗеҮәжҲӘ然дёҚеҗҢзҡ„и§Җй»һпјҢжҢҮеҮә"зҰҒжӯўеҲ©з”ЁиҫІжҘӯеңҹең°йҖІиЎҢе•ҶжҘӯе’Ңе·ҘжҘӯзҷјеұ•жңҖзөӮжңғеј„е·§жҲҗжӢҷ"гҖӮ[ 141] [ 141] [ 141]

жң¬зҜҖж‘ҳиҮӘеҚ°еәҰж°ЈеҖҷи®ҠеҢ–#дҪңзү©з”ўйҮҸдёӢйҷҚ гҖӮ

еҚ°еәҰзҡ„ж°ЈеҖҷи®ҠеҢ–е°Үе°ҚеҚ°еәҰ4е„„еӨҡиІ§еӣ°дәәеҸЈз”ўз”ҹи¶…еҮәжҜ”дҫӢзҡ„еҪұйҹҝгҖӮйҖҷжҳҜеӣ зӮәиЁұеӨҡдәәзҡ„йЈҹзү©гҖҒдҪҸжүҖе’Ң收е…ҘйғҪдҫқиіҙиҮӘ然иіҮжәҗжҸҗдҫӣгҖӮеҚ°еәҰжңүи¶…йҒҺ56%зҡ„дәәеҸЈеҫһдәӢиҫІжҘӯпјҢиҖҢеҸҲжңүе…¶д»–иЁұеӨҡдәәеңЁжІҝжө·ең°еҚҖи¬Җз”ҹгҖӮ[ 142]

еҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯз ”з©¶е§”е“Ўжңғ [ 143]

ж–јйҰ¬е“ҲжӢүд»Җзү№жӢүйӮҰзҡ„дёҖиҷ•и‘Ўиҗ„ең’

ж–јеқҰзұізҲҫйӮЈйғҪйӮҰзҡ„дёҖиҷ•иҢ¶ең’

й–ӢзҷјиЎҢйҠ·гҖҒе„ІеӯҳеҸҠеҶ·и—ҸеҹәзӨҺиЁӯж–ҪжүҖйңҖд№ӢжҠ•иіҮиҰҸжЁЎй җдј°е°Үзӣёз•¶йҫҗеӨ§гҖӮж”ҝеәңиҝ„д»Ҡд»Қз„Ўжі•жңүж•Ҳеҹ·иЎҢзӣёй—ңиЁҲз•«д»ҘжҸҗеҚҮе°ҚиЎҢйҠ·еҹәзӨҺиЁӯж–Ҫд№ӢжҠ•иіҮгҖӮеүҚиҝ°иЁҲз•«еҢ…еҗ«"иҲҲе»әиҫІжқ‘еҖүе„ІиЁӯж–Ҫ"гҖҒ"еёӮе ҙз ”з©¶иҲҮиіҮиЁҠз¶ІзөЎ"д»ҘеҸҠ"зҷјеұ•/еј·еҢ–иҫІжҘӯиЎҢйҠ·еҹәзӨҺиЁӯж–ҪгҖҒеҲҶзҙҡиҲҮжЁҷжә–еҢ–"зӯүгҖӮ[ 144]

еҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯз ”з©¶е§”е“ЎжңғпјҲICARпјүжҲҗз«Ӣж–ј1905е№ҙпјҢиІ иІ¬з ”з©¶е°ҺиҮҙ1970е№ҙд»ЈеҚ°еәҰз¶ иүІйқ©е‘Ҫзҡ„з ”з©¶гҖӮ ICARжҳҜиҫІжҘӯеҸҠзӣёй—ңзӣёй—ңй ҳеҹҹпјҲеҢ…жӢ¬з ”究е’Ңж•ҷиӮІпјүзҡ„жңҖй«ҳж©ҹж§ӢгҖӮ[ 145]

еҚ°еәҰж”ҝеәңж–ј2016е№ҙ5жңҲжҲҗз«ӢиҫІж°‘委員жңғпјҲFarmers Commissionпјүд»Ҙе…Ёйқўи©•дј°еҗ„й …иҫІжҘӯиЁҲз•«гҖӮ[ 146]

еҚ°еәҰж–ј2011е№ҙ11жңҲе®ЈдҪҲе°Қжңүзө„з№”зҡ„йӣ¶е”®йҖІиЎҢйҮҚеӨ§ж”№йқ©гҖӮж”№йқ©е°ҮеҢ…жӢ¬иҫІз”ўе“Ғзҡ„зү©жөҒе’Ңйӣ¶е”®гҖӮйҖҷй …е®Је‘Ҡеј•зҷјйҮҚеӨ§ж”ҝжІ»зҲӯиӯ°гҖӮ еҚ°еәҰж”ҝеәңж–ј2011е№ҙ12жңҲе°Үж”№йқ©ж“ұзҪ®пјҢзӯүеҫ…е…ұиӯҳеҮәзҸҫгҖӮеҚ°еәҰж–ј2012е№ҙзҙ„жү№еҮҶе–®дёҖе“ҒзүҢе•Ҷеә—зҡ„ж”№йқ©пјҢжӯЎиҝҺдҫҶиҮӘдё–з•Ңеҗ„ең°зҡ„е•Ҷ家д»Ҙж“Ғжңү100%зҡ„жүҖжңүж¬ҠеңЁеҚ°еәҰйӣ¶е”®еёӮе ҙйҒӢдҪңпјҢдҪҶиҰҒжұӮе–®дёҖе“ҒзүҢйӣ¶е”®е•ҶеҫһеҚ°еәҰжҺЎиіј30%зҡ„е•Ҷе“ҒгҖӮеҚ°еәҰж”ҝеәңз№јзәҢе°ҚеӨҡе“ҒзүҢе•Ҷеә—зҡ„йӣ¶е”®ж”№йқ©жҢҒдҝқз•ҷж…ӢеәҰгҖӮ[ 147]

ж–ј2012е№ҙеӨҸеӯЈпјҢеҚ°еәҰзҡ„еҗ«ж°ҙеұӨз”ұж–јжҠҪж°ҙйӣ»еҠӣиЈңиІјиҖҢе°ҺиҮҙж°ҙдҪҚжҖҘеҠҮдёӢйҷҚпјҢеӯЈйўЁйҷҚйӣЁйҮҸдёӢйҷҚ19%пјҢзөҰи©ІеңӢијёйӣ»з¶Іи·Ҝ её¶дҫҶйЎҚеӨ–еЈ“еҠӣпјҢиҖҢе°ҺиҮҙи©ІеңӢзҷјз”ҹеӨҡиө·еҒңйӣ»гҖӮжҜ”е“ҲзҲҫйӮҰзҡ„еӣһжҮүжҳҜжҸҗдҫӣиҫІж°‘и¶…йҒҺ1е„„зҫҺе…ғзҡ„жҹҙжІ№иЈңиІјпјҢдҫӣд»–еҖ‘йҒӢдҪңж°ҙжіөд»ҘжҠҪж°ҙгҖӮ[ 148]

еҚ°еәҰзёҪзҗҶзҙҚеҖ«еҫ·жӢүВ·иҺ«иҝӘ ж–ј2015е№ҙе®ЈдҪҲй җе®ҡеҲ°2022е№ҙе°ҮиҫІж°‘收е…Ҙзҝ»еҖҚгҖӮ[ 149] [ 150]

еҚ°еәҰжңүдәӣж“ҒжңүеҲ©еҹәжҠҖиЎ“еҸҠж–°еһӢзҮҹжҘӯжЁЎејҸзҡ„ж–°еүөе…¬еҸёд№ҹжӯЈеҠӘеҠӣпјҢиЁӯжі•и§ЈжұәеҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯеҸҠе…¶иЎҢйҠ·зҡ„е•ҸйЎҢгҖӮ[ 151]

иҫІжҘӯеӨҡе№ҙдҫҶе°ҚеҚ°еәҰ經жҝҹзҡ„иІўзҚ»дёҚж–·еўһејөгҖӮ經жҝҹиӘҝжҹҘйЎҜзӨәи©ІеңӢиҫІжҘӯж–ј2020-21иІЎж”ҝе№ҙеәҰзҡ„GDPдҪ”жҜ”жҳҜйҒҺеҺ»17е№ҙдҫҶйҰ–еәҰйҒ”еҲ°иҝ‘20%пјҢжҲҗзӮәе№ҙеәҰдёҚеҗҢз”ўжҘӯдёӯзҡ„е”ҜдёҖдә®й»һгҖӮ[ 152]

зҸҫд»ЈиҫІең°е’ҢиҫІжҘӯ經зҮҹдё»иҰҒз”ұж–јжҠҖиЎ“йҖІжӯҘпјҢеҢ…жӢ¬ж„ҹжё¬еҷЁгҖҒеҷЁжў°гҖҒж©ҹеҷЁе’ҢиіҮиЁҠжҠҖиЎ“пјҢиҖҢзҷјз”ҹеӨ§е№…и®ҠеҢ–гҖӮ[ 153]

еҖӢдәәеҢ–йӣ»е•Ҷе’ҢеёӮе ҙйҒӢдҪңеј•йҖІеҢ–иӮҘгҖҒзЁ®еӯҗгҖҒж©ҹеҷЁе’ҢиЁӯеӮҷзӯүиҫІз”ўе“ҒпјҢ幫еҠ©иҫІж°‘зЁ®жӨҚе„ӘиіӘз”ўе“ҒгҖӮжҸҗдҫӣж•ҷиӮІиӘІзЁӢзҡ„е…ҘеҸЈз¶Із«ҷи®“иҫІж°‘дәҶи§Јжңүй—ңиҫІжҘӯзҡ„еүөж–°зҹҘиӯҳпјҢиҖҢжҸҗеҚҮиҫІжҘӯе°Қ經жҝҹзҡ„иІўзҚ»гҖӮ[ 154] [ 155]

иҺ«иҝӘж”ҝеәңж–ј2015е№ҙзҷјиө·еӮізөұиҫІжҘӯжҢҜиҲҲиЁҲз•«пјҲParamparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PKVY) пјүпјҢзӣ®зҡ„зӮәдҝғйҖІжңүж©ҹиҫІжҘӯпјҢиҫІж°‘ж №ж“ҡиЁҲз•«зө„жҲҗз”ұ50еҗҚжҲ–жӣҙеӨҡиҫІж°‘зө„жҲҗзҡ„жңүж©ҹиҫІжҘӯйӣҶзҫӨпјҢж¶үеҸҠзҡ„иҫІең°зёҪйқўз©ҚиҮіе°‘зӮә50иӢұз•қпјҢеҲ©з”ЁеӮізөұеҸҜжҢҒзәҢзҡ„ж–№жі•еҲҶдә«жңүж©ҹиҫІжі•пјҢиЁҲз•«иЁӯе®ҡзҡ„жңҖеҲқзӣ®жЁҷжҳҜеҲ°2018е№ҙж“Ғжңү10,000еҖӢйӣҶзҫӨпјҢиҮіе°‘500,000иӢұз•қжңүж©ҹиҫІжҘӯиҖ•ең°пјҢз”ұж”ҝеәң"жүҝж“”иӘҚиӯүиІ»з”ЁпјҢдёҰдҪҝз”ЁеӮізөұиіҮжәҗдҝғйҖІжңүж©ҹиҫІжҘӯ"гҖӮж”ҝеәңеңЁ3е№ҙе…§жҸҗдҫӣжҜҸиӢұз•қ20,000еҚ°еәҰзӣ§жҜ”зҡ„иЈңеҠ©гҖӮ[ 156]

е–ҖжӢүжӢүйӮҰз“ҰдәһзҙҚеҫ·зҡ„иЁұеӨҡе°ҸиҫІжҲ¶е·ІеҜҰж–Ҫйӣ¶й җз®—иҮӘ然иҫІжҘӯ (ZBNF) зӯүе…¶д»–жңүж©ҹиҫІжҘӯжҠҖиЎ“гҖӮд»–еҖ‘еңЁйҒҺзЁӢдёӯжҺЎз”ЁжӣҙиҮӘ然е’Ңз”ҹж…Ӣзҡ„иҖ•дҪңж–№жі•пјҢжёӣе°‘жҲ–е®Ңе…ЁеҒңжӯўдҪҝз”Ёж®әиҹІеҠ‘е’Ңжңүе®ізҡ„еҢ–еӯёи—Ҙе“ҒпјҢиҖҢжёӣиј•"е№ҫеҚҒе№ҙдҫҶйҒҺеәҰдҪҝз”ЁеҢ–еӯёе“Ғе’ҢзЁ®жӨҚе–®дёҖзЁ®дҪңзү©пјҢд»ҘеҸҠзјәд№ҸеңҹеЈӨиӮҘеҠӣз®ЎзҗҶпјҢе°Үд»ҘеҫҖе„ӘиүҜеҸҠиӮҘжІғзҡ„жһ—ең°иҖ—жҗҚиҖҢйҖ жҲҗжҗҚе®ігҖӮ"гҖӮ[ 157]

йҡЁи‘—жңүж©ҹиҫІжҘӯиҫІжі•жҺЁе»ЈпјҢеҚ°еәҰиҫІжҘӯйғЁй–Җд№ҹжӯЈеҜҰж–Ҫжҝ•еәҰж„ҹжё¬еҷЁе’Ңдәәе·Ҙжҷәж…§зӯүж–°жҠҖиЎ“гҖӮиҫІж°‘дҪҝз”Ёжҝ•еәҰж„ҹжё¬еҷЁдҫҶзўәдҝқдёҚеҗҢдҪңзү©зҚІеҸ–зҡ„жә–зўәж°ҙйҮҸпјҢиҖҢиғҪжңҖеӨ§йҷҗеәҰжҸҗй«ҳдҪңзү©з”ўйҮҸгҖӮ"дәәе·Ҙжҷәж…§жҸҗдҫӣжӣҙжңүж•Ҳзҡ„ж–№ејҸдҫҶз”ҹз”ўгҖҒ收穫е’ҢйҠ·е”®иҫІдҪңзү©з”ўе“ҒпјҢдёҰеј·еҢ–еҒөжё¬еҮәжңүзјәйҷ·зҡ„иҫІдҪңзү©д»ҘжҸҗй«ҳеҒҘеә·иҫІдҪңзү©з”ҹз”ўзҡ„иғҪеҠӣ"пјҢйҖҷе°ҮжңүеҠ©ж–јжҸҗй«ҳиҫІдҪңзү©з”ўйҮҸпјҢжӯЈеҰӮзӘҒе°јиҘҝдәһ зұҚеӯёиҖ…Rayda BEN AYEDеңЁеҘ№з ”究дёӯжүҖжҸҸиҝ°дәәе·Ҙжҷәж…§е°Қж–јеҚ°еәҰзҡ„еҪұйҹҝгҖӮ[ 158]

еҚ°еәҰж¬ЎиҰҒдҪңзү©з”ўеҚҖ: P иұҶйЎһ, S з”ҳи”—, J й»ғйә», Cn жӨ°еӯҗ, C жЈүиҠұ, and T иҢ¶и‘ү

еҚ°еәҰдё»иҰҒдҪңзү©з”ўеҚҖ

еҚ°еәҰиҮӘ然

жӨҚиў« иҰҶи“ӢеҚҖеҹҹ

^ India economic survey 2018: Farmers gain as agriculture mechanisation speeds up, but more R&D needed . The Financial Express. 2018-01-29 [2019-01-08 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2019-01-08пјү. ^ CIA Factbook: India-Economy . [2018-11-17 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2021-03-18пјү. ^ Agriculture's share in GDP declines to 13.7% in 2012вҖ“13 . [2015-01-15 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2016-09-06пјү. ^ Staff, India Brand Equity Foundation Agriculture and Food in India дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2024-09-13. Accessed 2013-05-07

^ Labor force by agriculture sector in India . [2020-12-26 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2019-06-07пјү. ^ India outranks US, China with world's highest net cropland area . [2018-11-17 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2018-11-18пјү. ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 India's Agricultural Exports Climb to Record High дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2022-09-24., United States Department of Agriculture (2014)^ Agriculture in India: Agricultural Exports & Food Industry in India | IBEF . [2016-05-03 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2016-04-19пјү. ^ Home . [2017-09-07 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2017-09-08пјү. ^ Agriculture and Food Industry and Exports . IBEF. October 2024 [2024-11-03 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-11-20пјү. ^ Vaidyanathan, A. Fertilizers use in Indian agriculture. J. Soc. Econ. Dev. 24 (Suppl 1), 6вҖ“21 (2022). doi :10.1007/s40847-022-00224-x

^ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Bhakar, A., Singh, Y.V., Abhishek et al. Pesticides in India in the twenty-first century and their impact on biodiversity. Vegetos 36, 768вҖ“778 (2023). doi :10.1007/s42535-022-00434-y

^ Vaidyanathan, A. Fertilizers use in Indian agriculture. J. Soc. Econ. Dev. 24 (Suppl 1), 6вҖ“21 (2022). doi :10.1007/s40847-022-00224-x

^ Pedroso, T.M.A., Benvindo-Souza, M., de AraГәjo Nascimento, F. et al. Cancer and occupational exposure to pesticides: a bibliometric study of the past 10 years. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29, 17464вҖ“17475 (2022). doi :10.1007/s11356-021-17031-2

^ Vivek Chaudhary. The Indian state where farmers sow the seeds of death . The Guardian . 2019-07-01 [2024-05-06 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-09-13пјү. ^ 16.0 16.1 16.2 National Policy for Farmers дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ24 July 2020.. Department of Agriculture & Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India . pp 4. Accessed on 2021-03-22.^ 17.0 17.1 Agarwal, Kabir. Indian Agriculture's Enduring Question: Just How Many Farmers Does the Country Have? . The Wire. 2021-03-09 [2021-03-22 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2021-03-10пјү. ^ 18.0 18.1 Choudhary, Nitu. Who is a farmer? What is The Government's Definition Of A Farmer? . Smart Eklavya. 2020-12-09 [2021-03-22 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2021-04-11пјү пјҲиӢұеӣҪиӢұиҜӯпјү . ^ 19.0 19.1 FAOSTAT, 2014 data . Faostat.fao.org. [2011-09-17 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2012-04-07пјү. ^ Livestock and Poultry: World Markets & Trade (PDF) . United States Department of Agriculture. October 2011 [2011-12-28 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ (PDF) дәҺ2012-10-11пјү. ^ Sengupta, Somini. The Food Chain in Fertile India, Growth Outstrips Agriculture . The New York Times. 2008-06-22 [2010-04-23 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2014-07-23пјү. ^ 22.0 22.1 Rapid growth of select Asian economies . Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2009 [2011-12-19 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-09-13пјү. ^ 23.0 23.1 India Country Overview 2011 . World Bank. 2011 [2009-01-10 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2011-05-22пјү. ^ 24.0 24.1 India Allows Wheat Exports for the First Time in Four Years . Bloomberg L.P. 2011-09-08. ^ Fish and Rice in the Japanese Diet . Japan Review. 2006 [2011-12-21 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2012-04-06пјү. ^ India's foodgrain production hits record 332.22 mn tonne in 2023-24: Govt . The Economic Times. 2024-09-25 [2024-11-03 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-09-30пјү. ^ Rice exports in the Asia-Pacific region in 2023, by country or territory . Statista. [2024-11-03 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-03-04пјү. ^ The state of world fisheries and aquaculture, 2010 (PDF) . FAO of the United Nations. 2010 [2011-12-22 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ (PDF) дәҺ2011-09-15пјү. ^ Export of marine products from India (see statistics section) . Central Institute of Fisheries Technology, India. 2008. пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2013-07-01пјү. ^ Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles: India . Food and Africulture Organisation of the United Nations. 2011 [2011-12-22 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2012-06-13пјү. ^ 31.0 31.1 India: Global Food Security Index . [2018-01-17 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2012-07-12пјү. ^ 32.0 32.1 Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy . Reserve Bank of India: India's Central Bank. 2011 [2011-12-22 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2012-01-11пјү. ^ World Wheat, Corn and Rice . Oklahoma State University, FAOSTAT. пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2015-06-10пјү. ^ Indian retail: The supermarket's last frontier . The Economist. 2011-12-03 [2011-12-28 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-03-31пјү. ^ Sinha, R.K. Emerging Trends, Challenges and Opportunities presentation, on publications page, see slides 7 through 21 . National Seed Association of India. 2010 [2011-12-18 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2011-11-15пјү. ^ India sustainable rice cuts water use and emissions . European Investment Bank. [2022-12-23 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2022-12-23пјү пјҲиӢұиҜӯпјү . ^ Deshpande, Tanvi. Climate Change Is Making India's Monsoon More Erratic . www.indiaspend.com. 2021-10-11 [2022-12-23 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2022-12-23пјү пјҲиӢұиҜӯпјү . ^ Koshy, Jacob. Explained | Shifting monsoon patterns . The Hindu. 2022-09-25 [2022-12-23 ] . ISSN 0971-751X еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2022-12-23пјү пјҲеҚ°еәҰиӢұиҜӯпјү . ^ The Story of India: a PBS documentary . Public Broadcasting Service, United States. [2017-08-23 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2017-08-25пјү. ^ Roy, Mira. Agriculture in the Vedic Period (PDF) . Indian Journal of History of Science. 2009, 44 (4): 497вҖ“520 [14 January 2019] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ (PDF) дәҺ2020-08-25пјү. ^ 41.0 41.1 Agri - Kaleidoscope: AGRICULTURAL HERITAGE AGR.102 AGRICULTURAL HERITAGE OF INDIA 1+0 THEORY . KIRAN. [2024-10-31 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2022-06-28пјү. ^ Indian Agriculture and IFFCO (PDF) . Quebec Reference Center for Agriculture and Agri-food. [2019-01-14 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ (PDF) дәҺ2019-01-14пјү. ^ Fuller; Korisettar, Ravi; Venkatasubbaiah, P.C.; Jones, Martink.; et al. Early plant domestications in southern India: some preliminary archaeobotanical results (PDF) . Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 2004, 13 (2): 115вҖ“129 [2011-12-22 ] . Bibcode:2004VegHA..13..115F S2CID 8108444 doi:10.1007/s00334-004-0036-9 еҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ (PDF) еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2012-08-10пјү. ^ Tamboli and Nene. Science in India with Special Reference to Agriculture (PDF) . Agri History. [2011-12-22 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ (PDF) еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2012-02-05пјү. ^ Gupta, p. 57

^ Harris & Gosden, p. 385

^ Lal, R. Thematic evolution of ISTRO: transition in scientific issues and research focus from 1955 to 2000. Soil and Tillage Research. August 2001, 61 (1вҖ“2): 3вҖ“12 [3]. Bibcode:2001STilR..61....3L doi:10.1016/S0167-1987(01)00184-2 ^ 48.0 48.1 agriculture, history of . EncyclopГҰdia Britannica 2008.^ Shaffer, pp. 310вҖ“311

^ Rolph, George. Something about sugar: its history, growth, manufacture and distribution . 1873 [2020-04-20 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2020-10-23пјү. ^ Agribusiness Handbook: Sugar beet white sugar . Food and Agriculture Organization, United Nations. 2009 [2020-04-20 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2020-10-23пјү. ^ Sugarcane: Saccharum Officinarum (PDF) . USAID, Govt of United States: 7.1. 2006 [2017-05-04 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ (PDF) еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2013-11-06пјү. ^ Mintz, Sidney. Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History . Penguin. 1986. ISBN 978-0-14-009233-2 ^ Indian indentured labourers . The National Archives, Government of the United Kingdom. 2010 [2012-02-06 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2015-03-23пјү. ^ Forced Labour . The National Archives, Government of the United Kingdom. 2010 [2012-02-06 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2016-12-04пјү. ^ Laurence, K. A Question of Labour: Indentured Immigration Into Trinidad & British Guiana, 1875вҖ“1917. St Martin's Press. 1994. ISBN 978-0-312-12172-3 ^ St. Lucia's Indian Arrival Day . Caribbean Repeating Islands. 2009. пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2020-10-23пјү. ^ Lai, Walton. Indentured labor, Caribbean sugar: Chinese and Indian migrants to the British West Indies, 1838вҖ“1918. Johns Hopkins University Press. 1993. ISBN 978-0-8018-7746-9 ^ Steven Vertovik (Robin Cohen, ed.). The Cambridge survey of world migration . Cambridge; New York : Cambridge University Press. 1995: 57вҖ“68 . ISBN 978-0-521-44405-7 ^ Roy 2006

^ Kumar 2006

^ 62.0 62.1 The Government of Punjab . Human Development Report 2004, Punjab (PDF) (жҠҘе‘Ҡ). 2004 [2011-08-09 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ (PDF) дәҺ2011 -07-08пјү. ^ Brief history of wheat improvement in India . Directorate of Wheat Research, ICAR India. 2011 [2011-12-20 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2011-11-17пјү. ^ Pro. M. S. Swaminathan A Memoir (PDF) . National Academy of Agticultural Sciences. 2024 [2024-09-24 ] . ^ "Sikkim to become a completely organic state by 2015" дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2014-07-08.. The Hindu . 2010-09-09. Retrieved 2012-11-29.^ "Sikkim makes an organic shift" . Times of India . 2010-05-07. Retrieved 2012-11-29.^ "Sikkim 'livelihood schools' to promote organic farming" дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ28 May 2013.. Hindu Business Line . 2010-08-06. Retrieved 2012-11-29.^ "Sikkim races on organic route" . Telegraph India . 2011-12-12. Retrieved 2012-11-29.^ Martin, K. a. State to switch fully to organic farming by 2016: Mohanan . The Hindu. 2014-10-19 [2014-11-07 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2021-11-08пјү. ^ CM: Will Get Total Organic Farming State Tag by 2016 . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2014-11-10пјү. ^ 71.0 71.1 Electricity use in agriculture sector jumps to 37.1% since 2009-10 . Business Standard. 2024-01-28 [2024-10-31 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-01-25пјү. ^ S. Siebert et al (2010), Groundwater use for irrigation вҖ“ a global inventory пјҲйЎөйқўеӯҳжЎЈеӨҮд»Ҫ пјҢеӯҳдәҺдә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ пјү, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 14, pp. 1863вҖ“1880

^ Economic Times: How to solve the problems of India's rain-dependent on agricultural land . [2024-11-25 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2015-07-29пјү. ^ PM Launches Rs 6,000 Crore Groundwater Management Plan пјҲйЎөйқўеӯҳжЎЈеӨҮд»Ҫ пјҢеӯҳдәҺдә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ пјү, NDTV, 2019-12-25.^ State of Agriculture in India . PRS Legislative Research. [2024-10-21 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-11-12пјү. Currently, about 51% of the agricultural area cultivating food grains is covered by irrigation.[36] The rest of the area is dependent on rainfall (rain-fed agriculture). ^ National Water Development Agency дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2017-09-30. Ministry of Water Resources, Govt of India (2014)^ India's thirsty crops upset water equation . [2018-11-17 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2018-11-18пјү. ^ 78.0 78.1 Biswas, Soutik. India election 2019: How sugar influences the world's biggest vote . BBC.com (2019-05-08) (BBC). BBC. 2019 [2019-05-13 ] . ^ Bhungroo . UN. [2024-10-31 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-02-21пјү. ^ India: Basic Information . United States Department of Agriculture вҖ“ Economic Research Service. August 2011 [2015-05-08 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2015-07-17пјү. ^ FAOSTAT: Production-Crops, 2010 data . Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2011. пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2013-01-14пјү. ^ Adam Cagliarini and Anthony Rush. Bulletin: Economic Development and Agriculture in India (PDF) . Reserve Bank of Australia: 15вҖ“22. June 2011 [2012-01-08 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ (PDF) дәҺ2012-03-22пјү. ^ Food and Agricultural commodities production / Commodities by country / India . FAOSTAT . 2013 [2016-05-03 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2016-06-02пјү. ^ Production / Crops / India . FAOSTAT . 2014 [2016-05-03 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2016-11-22пјү. ^ 85.0 85.1 85.2 85.3 85.4 85.5 85.6 85.7 е…¬еҷё/й ӯ

^ Agricultural Production in india, 2019 . [2020-12-25 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2016-11-12пјү. ^ Data checks suggest there is a difference between FAO's statistics office and Reserve Bank of India estimates; these differences are small and may be because of the fiscal year start months.

^ India agriculture proction . [2020-12-25 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2016-11-12пјү. ^ production of crops in India . [2020-12-25 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2016-11-12пјү. ^ 90.0 90.1 90.2 Country Rank in the World, by commodity . Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2011 [2011-12-19 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2012-04-15пјү. ^ These are food and agriculture classification groups. For definition with list of botanical species covered under each classification, consult FAOSTAT of the United Nations; Link: http://faostat.fao.org/site/384/default.aspx дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2012-01-01.

^ L.P. Yuan. A Scientist's Perspective on Experience with SRI in CHINA for Raising the Yields of Super Hybrid Rice (PDF) . 2010. пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ (PDF) еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2011-11-20пјү. ^ Indian farmer sets new world record in rice yield . The Philippine Star. 2011-12-18. пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2012-09-10пјү. ^ Grassroots heroes lead Bihar's rural revolution . India Today. 2012-01-10 [2012-01-12 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2013-01-03пјү. ^ System of Rice Intensification . Cornell University. 2011 [2012-01-12 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2011-12-19пјү. ^ 96.0 96.1 Deficit rains spare horticulture, record production expected Livemint, S Bera, Hindustan Times (2015-01-19)^ Final Area & Production Estimates for Horticulture Crops for 2012вҖ“2013 дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2015-02-06. Government of India (2014)^ Horticulture output дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2015-01-18. Horticulture Board of India^ 99.0 99.1 99.2 99.3 99.4 Horticulture in India (PDF) . MOSPI, Government of India. 2014 [2015-05-16 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ (PDF) еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2015-08-07пјү. ^ Paull, John & Hennig, Benjamin (2016) rider Vinay Kumar Atlas of Organics: Four Maps of the World of Organic Agriculture дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ24 July 2019. Journal of Organics. 3(1): 25вҖ“32.

^ Paull, John (2016) Organics Olympiad 2016: Global Indices of Leadership in Organic Agriculture дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2017-11-12., Journal of Social and Development Sciences. 7(2):79вҖ“87

^ BioProtein Production (PDF) . [2018-01-31 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ (PDF) еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2017-05-10пјү. ^ Food made from natural gas will soon feed farm animals вҖ“ and us . [2018-01-31 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2019-12-12пјү. ^ New venture selects Cargill's Tennessee site to produce Calysta FeedKind Protein . [2018-01-31 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2019-12-30пјү. ^ Assessment of environmental impact of FeedKind protein (PDF) . [2017-06-20 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ (PDF) еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2019-08-02пјү. ^ Vadivelu, A. and Kiran, B.R., 2013. Problems and prospects of agricultural marketing in India: An overview. International journal of agricultural and food science, 3(3), pp.108вҖ“118.[1]

^ 107.0 107.1 107.2 Dahiwale, S. M. Consolidation of Maratha Dominance in Maharashtra. Economic and Political Weekly. 1995-02-11, 30 (6): 340вҖ“342. JSTOR 4402382 ^ National Federation of Cooperative Sugar Factories Limited . Coopsugar.org. [2011-12-27 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2012-02-25пјү. ^ Patil, Anil. Sugar cooperatives on death bed in Maharashtra . Rediff India. 2007-07-09 [2011-12-27 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2011-08-28пјү. ^ Mathew, George. Baviskar, B.S. , зј–. Inclusion and exclusion in local governance : field studies from rural India . London: SAGE. 2008: 319 [2019-12-11 ] . ISBN 9788178298603еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-09-13пјү. ^ Archived copy (PDF) . [2019-05-09 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ (PDF) еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2015-09-24пјү. ^ K. V. Subrahmanyam; T. M. Gajanana. Cooperative Marketing of Fruits and Vegetables in India . Concept Publishing Company. 2000: 45вҖ“60 [2019-05-09 ] . ISBN 978-81-7022-820-2еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-09-13пјү. ^ Scholten, Bruce A. India's white revolution Operation Flood, food aid and development . London: Tauris Academic Studies. 2010: 10 [2020-12-06 ] . ISBN 9781441676580еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-09-13пјү. ^ Global Tractor Market Analysis Available to AEM Members from Agrievolution Alliance Association of Equipment Manufacturers дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2015-12-08., Wisconsin, USA (2014)^ India proves fertile ground for tractor makers дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2024-09-13. The Financial Times (8 April 2014) (subscription required)^ India Country Overview 2008 . World Bank. 2008 [2009-01-10 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2011-05-22пјү. ^ SMALLHOLDER FARMERS IN INDIA: FOOD SECURITY AND AGRICULTURAL POLICY (PDF) . Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2003. [ж°ёд№…еӨұж•ҲйҖЈзөҗ ^ How much should a fair price of farmer's produce be? . [2018-02-10 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-09-13пјү. ^ Singh, Saroj Kumar. Progress and Performance of Agriculture in India (PDF) . Journal of Agroecology and Natural Resource Management. January-March, 2016, 3 (1): 67вҖ“71 [2024-11-01 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ (PDF) дәҺ2018-04-11пјү. ^ Singh, B P. Present Position of Agriculture in India (PDF) . International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR). April 2016, 5 (4) [2024-11-01 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ (PDF) дәҺ2024-09-04пјү. ^ Production Crops вҖ“ Yield by Country дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2013-01-14., FAO United Nations 2011^ Ashok Gulati; Pallavi Rajkhowa; Pravesh Sharma. Making Rapid Strides- Agriculture in Madhya Pradesh: Sources, Drivers, and Policy Lessons (PDF) (жҠҘе‘Ҡ). ICRIER: 9. April 2017 [2019-01-11 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ (PDF) дәҺ2019-01-12пјү. Figure 8: State-wise Agriculture Growth Rate (2005вҖ“06 to 2014вҖ“15) ^ 123.0 123.1 123.2 123.3 123.4 Mahadevan, Renuka. Productivity growth in Indian agriculture: The role of globalization and economic reform. Asia-Pacific Development Journal. December 2003, 10 (2): 57вҖ“72. S2CID 13201950 doi:10.18356/5728288b-en ^ Rapid growth of select Asian economies (PDF) . Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2006. [ж°ёд№…еӨұж•ҲйҖЈзөҗ ^ 125.0 125.1 India: Priorities for Agriculture and Rural Development . World Bank. [2009-01-08 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2009-01-21пјү. ^ Biello, David. Is Northwestern India's Breadbasket Running Out of Water? . Scientificamerican.com. 2009-11-11 [2011-09-17 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2011-09-24пјү. ^ Chauhan, Chetan. UN climate panel warns India of severe food, water shortage . Hindustan Times. 2014-04-01 [2014-03-31 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2014-04-01пјү. ^ Agricultural Statistics at a Glance 2004 . 2004. пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ (XLS) еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2009-04-10пјү. ^ Sankaran, S. 28. Indian Economy: Problems, Policies and Development. : 492вҖ“493. ^ Satellites Unlock Secret To Northern India's Vanishing Water . Sciencedaily.com. 2009-08-19 [2011-09-17 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2011-03-21пјү. ^ Columbia Conference on Water Security in India (PDF) . [2011-09-17 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ (PDF) еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2010-06-22пјү. ^ Pearce, Fred. Keepers of the spring: reclaiming our water in an age of globalisation, By Fred Pearce, p. 77 . Island Press. 2004-11-01 [17 September 2011] . ISBN 9781597268936еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-09-13пјү. ^ Zakaria, Fareed. "Zakaria: Is India the broken BRIC?" CNN , 2011-12-21.

^ 134.0 134.1 National Crime Reports Bureau, ADSI Report Annual вҖ“ 2012 дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2013-08-10. Government of India, p. 242, Table 2.11

^ Nagraj, K. Farmers suicide in India: magnitudes, trends and spatial patterns (PDF) . 2008. пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ (PDF) еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2011-05-12пјү. ^ GruГЁre, G. & Sengupta, D. (2011), Bt cotton and farmer suicides in India: an evidence-based assessment, The Journal of Development Studies, 47(2), 316вҖ“337

^ Schurman, R. (2013), Shadow space: suicides and the predicament of rural India, Journal of Peasant Studies, 40(3), 597вҖ“601

^ Das, A. (2011), Farmers' suicide in India: implications for public mental health, International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 57(1), 21вҖ“29

^ Singh, Shail Bala. Rural marketing environment problems and strategies (PDF) . 2003 [2021-03-30 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ (PDF) дәҺ2018-10-25пјү. ^ 140.0 140.1 National Policy for Farmers, 2007 дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2015-08-24.^ 141.0 141.1 141.2 The Telegraph. 23 July 2007 'Prohibiting the use of agricultural land for industries is ultimately self-defeating'

^ UNDP. India and Climate Change Impacts . [2010-02-11 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2011-03-17пјү. ^ Effect of Climate Change on Agriculture . PIB.GOV.IN. [2023-07-26 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-08-02пјү. ^ Agriculture marketing дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2008-02-05. india.gov Retrieved in February 2008^ Objectives дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2007-10-24. Indian agricultural research institute, Retrieved in December 2007^ Farmers Commission . [2009-11-23 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№ еӯҳжЎЈдәҺ2010-05-11пјү. ^ Poonam, Rani; Geeta, Shiromani. Foreign Direct Investment in Retail Sector (PDF) . Global Journal of Commerce & Management Perspective: 19вҖ“28. [2024-11-02 ] . ^ " Drought fears loom in India as monsoon stalls." дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2012-08-05. al Jazeera , 2012-08-058.^ PM Modi: Target to double farmers' income by 2022 , The Indian Express , 2016-02-28 [2016-05-15 ] , пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2016-05-03пјү ^ A decade under Modi: FarmersвҖҷ income yet to double, MSP growth slows down A quick look at how the Modi government fared on improving the agriculture sector in India. . Scroll.in. 2024-02-14 [2024-11-02 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-08-31пјү. ^ Tech in Asia вҖ“ Connecting Asia's startup ecosystem . www.techinasia.com. [2016-06-04 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2016-06-30пјү пјҲзҫҺеӣҪиӢұиҜӯпјү . ^ Agri share in GDP hit 20% after 17 years: Economic Survey . www.downtoearth.org.in. 2021-01-29 [2021-03-28 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2021-04-18пјү пјҲиӢұиҜӯпјү . ^ Agriculture Technology | National Institute of Food and Agriculture . nifa.usda.gov. [2021-03-28 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2021-03-05пјү. ^ Applying modern tech to agriculture . www.downtoearth.org.in. 2019-08-05 [2021-03-28 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2021-01-29пјү пјҲиӢұиҜӯпјү . ^ E-Commerce for Ag Business: Advantages and Challenges . Penn State Extension. [2021-03-28 ] . пјҲеҺҹе§ӢеҶ…е®№еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2021-03-14пјү пјҲиӢұиҜӯпјү . ^ 10 important government schemes for agriculture sector дә’иҒ”зҪ‘жЎЈжЎҲйҰҶ зҡ„еӯҳжӘ” пјҢеӯҳжЎЈж—Ҙжңҹ2021-07-23., India today, 2019-08-30.^ MГјnster, Daniel. Zero Budget Natural Farming and Bovine Entanglements in South India . RCC Perspectives: Transformations in Environment and Society. March 2017, (1): 25вҖ“32 [2023-04-29 ] . doi:10.5282/RCC/7771 еӯҳжЎЈ дәҺ2024-09-13пјү пјҲиӢұиҜӯпјү . ^ Ben Ayed, Rayda; Hanana, Mohsen. Artificial Intelligence to Improve the Food and Agriculture Sector. Journal of Food Quality. 2021-04-22, 2021 : e5584754. ISSN 0146-9428 doi:10.1155/2021/5584754 пјҲиӢұиҜӯпјү .

Agarwal, Ankit (2011), "Theory of Optimum Utilisation of Resources in agriculture during the Gupta Period" [ж°ёд№…еӨұж•ҲйҖЈзөҗ ISSN 2249-748X .Akhilesh, K. B., and Kavitha Sooda. "A Study on Impact of Technology Intervention in the Field of Agriculture in India." in Smart Technologies (Springer, Singapore, 2020) pp. 373вҖ“385.

Bhagowalia, Priya, S. Kadiyala, and D. Headey. "Agriculture, income and nutrition linkages in India: Insights from a nationally representative survey." (2012). online

Bhan, Suraj, and U. K. Behera. "Conservation agriculture in IndiaвҖ“Problems, prospects and policy issues." International Soil and Water Conservation Research 2.4 (2014): 1вҖ“12.

Bharti, N. (2018), "Evolution of agriculture finance in India: a historical perspective", Agricultural Finance Review, Vol. 78 No. 3, pp. 376вҖ“392. https://doi.org/10.1108/AFR-05-2017-0035

Brink, Lars. "Support to Agriculture in India in 1995-2013 and the Rules of the WTO." International Agricultural Trade Research Consortium (IATRC) Working Paper 14-01 (2014) online .

Brown, Trent. Farmers, Subalterns, and activists: social politics of sustainable agriculture in India (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Chauhan, Bhagirath Singh, et al. "Global warming and its possible impact on agriculture in India." in Advances in agronomy (Academic Press, 2014) pp. 65вҖ“121.online [еӨұж•ҲйҖЈзөҗ

Chengappa, P. G. "Presidential Address: Secondary Agriculture: A Driver for Growth of Primary Agriculture in India." Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics 68.902-2016-66819 (2013): 1вҖ“19. online

Dev, S. Mahendra, Srijit Mishra, and Vijay Laxmi Pandey. "Agriculture in India: Performance, Challenges, and Opportunities." in A Concise Handbook of the Indian Economy in the 21st Century (Oxford University Press, 2014) pp. 321вҖ“350.

Goyal, S. & Prabha, & Rai, Dr & Singh, Shree Ram. Indian Agriculture and Farmers-Problems and Reforms. (2016)

Kekane Maruti Arjun. "Indian, Agriculture- Status, Importance and Role in Indian Economy," International Journal of Agriculture and Food Science Technology , ISSN 2249-3050 , Volume 4, Number 4 (2013), pp. 343вҖ“346.

Kumar, Anjani, Krishna M. Singh, and Shradhajali Sinha. "Institutional credit to agriculture sector in India: Status, performance and determinants." Agricultural Economics Research Review 23.2 (2010): 253-264 online .

Manida, Mr M., and G. Nedumaran. "Agriculture In India: Information About Indian Agriculture & Its Importance." Aegaeum Journal , 8#3 (2020) online

Mathur, Archana S., Surajit Das, and Subhalakshmi Sircar. "Status of agriculture in India: trends and prospects." Economic and political weekly (2006): 5327-5336 online .

Nedumaran, Dr G. "E-Agriculture and Rural Development in India." (2020). online

Ramakumar, R. "Large-scale Investments in Agriculture in India." IDS Bulletin 43 (2012): 92вҖ“103. online

Ramakumar, R. "Agriculture and the Covid-19 Pandemic: An Analysis with Special Reference to India." Review of Agrarian Studies 10.2369-2020-1856 (2020) online .

Saradhi, Byra Pardha, et al. "Significant Trends in the Digital Transformation of Agriculture in India." International Journal of Grid and Distributed Computing 13.1 (2020): 2703-2709 [2] .

Sharma, Shalendra D., Development and Democracy in India , Lynne Rienner Publishers: 125вҖ“, 1999, ISBN 978-1-55587-810-8 State of Indian Agriculture 2011вҖ“12 . New Delhi: Government of India, Ministry of Agriculture, Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, March 2012

Indian Agriculture . U.S. Library of Congress.Indian Agriculture Data . Statistical information about Agriculture in India.Government of India, Ministry of Agriculture, Department of Agriculture & Cooperation website Indian Council for Agricultural Research Home Page. Principal crops of India and problems with Indian agriculture A collection of statistics (from India Statistical Report, 2011) along with sections of this Wikipedia article and YouTube videos.Brighter Green Policy Paper: Veg or NonVeg, India at a Crossroads A December 2011 policy paper analysing the forces behind the rising consumption and production of meat, eggs, and dairy products in India, and the effects on India's people, environment, animals, and the global climate.Mukherji, Biman. India's farmers start to mechanise amid a labour shortage, increasing productivity. - WSJ.com . Wall Street Journal (Online.wsj.com). 28 October 2013 [2013-10-30 ] .