American Woman Suffrage Association

|

Read other articles:

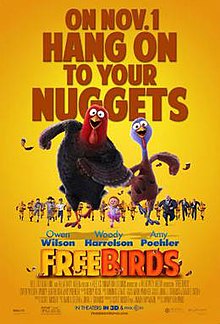

2013 computer-animated film by Jimmy Hayward For other uses, see Freebirds. Free BirdsTheatrical release posterDirected byJimmy HaywardScreenplay byJimmy HaywardScott MosierStory byDavid I. SternJohn J. StraussProduced byScott Mosier[1]Starring Owen Wilson Woody Harrelson Amy Poehler Edited byChris CartagenaMusic byDominic Lewis[2]ProductioncompaniesRelativity MediaReel FX Animation StudiosDistributed byRelativity MediaRelease date November 1, 2013 (2013-11-01) ...

Mario Montero Schmidt Ministro de Agricultura de Chile 14 de noviembre-20 de noviembre de 1954Presidente Carlos Ib├Ī├▒ez del CampoPredecesor Eugenio Su├Īrez HerrerosSucesor Ricardo Hepp Dubiau Ministro de Tierras y Colonizaci├│n de Chile 5 de junio de 1954-6 de enero de 1955Presidente Carlos Ib├Ī├▒ez del CampoPredecesor Diego Lira VergaraSucesor Enrique Casas Garc├Ła Informaci├│n personalNombre de nacimiento Mario Alejandro Montero Schmidt Nacimiento 28 de enero de 1918 Santa Cruz (Chile) Fal...

ą¤č¢ą▓ąĮč¢čćąĮąŠ-ąŚą░čģč¢ą┤ąĮąĖą╣ čāąĮč¢ą▓ąĄčĆčüąĖč鹥čé 42┬░03ŌĆ▓17ŌĆ│ ą┐ąĮ. čł. 87┬░40ŌĆ▓26ŌĆ│ ąĘčģ. ą┤. / 42.05485300002777649┬░ ą┐ąĮ. čł. 87.67394500002778557┬░ ąĘčģ. ą┤. / 42.05485300002777649; -87.67394500002778557ąÜąŠąŠčĆą┤ąĖąĮą░čéąĖ: 42┬░03ŌĆ▓17ŌĆ│ ą┐ąĮ. čł. 87┬░40ŌĆ▓26ŌĆ│ ąĘčģ. ą┤. / 42.05485300002777649┬░ ą┐ąĮ. čł. 87.67394500002778557┬░ ąĘčģ. ą┤. / 42.0548...

58th edition of the Miss Universe competition Miss Universe 2009Miss Universe 2009, Stefan├Ła Fern├ĪndezDateAugust 23, 2009PresentersBilly BushClaudia JordanEntertainmentHeidi MontagFlo RidaKelly RowlandDavid GuettaVenueImperial Ballroom, Atlantis Paradise Island, Nassau, The BahamasBroadcasterNBC/Telemundo (international)ZNS-TV (official broadcaster)Entrants83Placements15WithdrawalsAntigua and BarbudaDenmarkKazakhstanSri LankaTrinidad and TobagoTurks and CaicosReturnsBulgariaEthiopiaGuyanaIc...

ą£č¢ą║ąĄą╗čī ąæčĆčāąĮąĄčé ą£č¢ą║ąĄą╗čīąØą░čĆąŠą┤ąČąĄąĮąĮčÅ 6 čüč¢čćąĮčÅ 1919(1919-01-06)ą£ą░ąĮą░ą║ąŠčĆ, ą£ą░ą╗čīąŠčĆą║ą░, ąæą░ą╗ąĄą░čĆčüčīą║č¢ ąŠčüčéčĆąŠą▓ąĖ[d], ąæą░ą╗ąĄą░čĆčüčīą║č¢ ąŠčüčéčĆąŠą▓ąĖ[d], ąåčüą┐ą░ąĮč¢čÅąĪą╝ąĄčĆčéčī 29 ą▒ąĄčĆąĄąĘąĮčÅ 2007(2007-03-29) (88 čĆąŠą║č¢ą▓) ą£ą░ąĮą░ą║ąŠčĆ, ą£ą░ą╗čīąŠčĆą║ą░, ąæą░ą╗ąĄą░čĆčüčīą║č¢ ąŠčüčéčĆąŠą▓ąĖ[d], ąæą░ą╗ąĄą░čĆčüčīą║č¢ ąŠčüčéčĆąŠą▓ąĖ[d], ąåčüą┐ą░ąĮč¢čÅąÜčĆą░茹Įą░ ąåčüą┐ą░ąĮč¢čÅąöč¢čÅą╗čīąĮč¢čüčéčī čģčāą┤ąŠą...

48.87741816.674576Koordinaten: 48┬░ 52ŌĆ▓ 38,7ŌĆ│ N, 16┬░ 40ŌĆ▓ 28,5ŌĆ│ O Pavlov I p1 Blick ├╝ber die Fundstelle (2014) Blick ├╝ber die Fundstelle (2014) p4 Pavlov I (Tschechien) Wann vor ca. 27'000ŌĆō30'000 Jahren Wo Pavlov, Tschechien Pavlov I war die Fundstelle einer gro├¤fl├żchigen, rund 30.000 Jahre alten jungpal├żolithischen Freilandstation in S├╝dm├żhren/Tschechien. Sie lag 20 km s├╝dlich von Br├╝nn am Ortsrand der heutigen Gemeinde Pavlov. Zwisc...

Election in Colorado Main article: 1900 United States presidential election 1900 United States presidential election in Colorado ← 1896 November 6, 1900 1904 → Nominee William Jennings Bryan William McKinley Party Democratic Republican Home state Nebraska Ohio Running mate Adlai Stevenson I Theodore Roosevelt Electoral vote 4 0 Popular vote 122,733 93,072 Percentage 55.43% 42.04% County Results Bryan 40-50% 50-60% ...

Radio stationSports Radio DetroitBroadcast areaWorldwideBrandingSRD/Sports Radio DetroitProgrammingFormatSports TalkOwnershipOwnerFormerly SRD Productions, LLCHistoryFirst air dateSeptember 25, 2012Former call signsLetsGoWingsMedia.com (2011)LetsGoWingsRadio.com (2012)LinksWebcastListen LiveWebsiteSportsRadioDetroit.com Sports Radio Detroit (SRD) was a Detroit-based internet sports broadcasting and news network covering Detroit's professional sports teams Detroit Lions, Detroit Tigers, Detroi...

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Museumsdorf Niedersulz ŌĆō news ┬Ę newspapers ┬Ę books ┬Ę scholar ┬Ę JSTOR (January 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Museum entrance Museumsdorf Niedersulz Museumsdorf Niedersulz is an open-air museum in Austria that displays traditional bui...

1955 American filmThe African LionDirected byJames AlgarWritten byJames AlgarWinston HiblerProduced byWalt DisneyBen SharpsteenNarrated byWinston HiblerCinematographyAlfred MilotteElma MilotteEdited byNorman R. PalmerMusic byPaul J. SmithProductioncompanyWalt Disney ProductionsDistributed byBuena Vista Film DistributionRelease date September 14, 1955 (1955-09-14)[1] Running time75 minutesCountryUnited StatesLanguageEnglishBox office$2.1 million (US)[2] The Afric...

American actor and musician (born 1971) Jared LetoLeto at the 2016 San Diego Comic-ConBornJared Joseph Leto (1971-12-26) December 26, 1971 (age 51)Bossier City, Louisiana, U.S.Other names Bartholomew Cubbins Angakok Panipaq Alma materSchool of Visual ArtsOccupations Actor musician Years active1992ŌĆōpresentWorksFilmographydiscographysongsPartner(s)Cameron Diaz (1999ŌĆō2003)Valery Kaufman (2015ŌĆō2022)FamilyShannon Leto (brother)AwardsFull list[a]Musical careerGenre...

Spanish newspaper El Peri├│dico de CatalunyaTypeDaily newspaperFormatBerlinerOwner(s)Editorial Prensa Ib├®ricaFounder(s)Antonio Asensio PizarroEditorAlbert S├ĪezFounded26 October 1978; 45 years ago (1978-10-26)Political alignmentCentre-leftSocial liberalismProgressivismCatalanismLanguageSpanish and CatalanHeadquartersL'Hospitalet de Llobregat, Catalonia, SpainCirculation119,374 (2011)Sister newspapersSportWebsiteSpanish elperiodico.comCatalan, elperiodico.cat El Peri├│dico d...

Hospital in West Yorkshire, EnglandStanley Royd HospitalWakefield and Pontefract Community Health NHS TrustStanley Royd Hospital (since converted into flats)Shown in West YorkshireGeographyLocationWakefield, West Yorkshire, EnglandCoordinates53┬░41ŌĆ▓27ŌĆ│N 1┬░29ŌĆ▓18ŌĆ│W / 53.6909┬░N 1.4884┬░W / 53.6909; -1.4884OrganisationCare systemNHSTypeSpecialistServicesEmergency departmentN/ASpecialityPsychiatric and Learning Disability HospitalHistoryOpened1818Closed1995LinksLi...

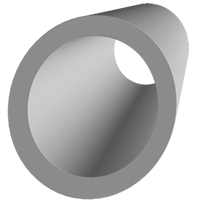

Rundrohr PVC-U Druckrohr transparent Ein Rohr (auch: eine R├Čhre) ist ein l├żnglicher Hohlk├Črper, dessen L├żnge in der Regel wesentlich gr├Č├¤er als sein Durchmesser ist. Im Gegensatz zu einem Schlauch ist ein Rohr aus relativ unflexiblem Material gefertigt. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Verwendung 2 Werkstoffe und Herstellung 2.1 Metallrohre 2.1.1 Wickelfalzrohre 2.1.2 Geschwei├¤t 2.1.3 Nahtlos 2.2 Kunststoffrohre 2.3 Glasrohre 3 Verbindungen 4 Verarbeitung 5 Abmessungen und Gr├Č├¤enbezeichnungen 5....

For the federal constituency represented in the Dewan Rakyat, see Keningau (federal constituency). For the language, see Keningau Murut language. Town and district capital in Sabah, MalaysiaKeningau Pekan KeningauTown and district capitalKeningau town centre.Coordinates: 5┬░20ŌĆ▓00ŌĆ│N 116┬░10ŌĆ▓00ŌĆ│E / 5.33333┬░N 116.16667┬░E / 5.33333; 116.16667Country MalaysiaState SabahDivisionInteriorDistrictKeningauMunicipality1 January 2022Government ŌĆó Typ...

1971 single by Led Zeppelin For other songs with this title, see Black dog#Music. Black DogPicture sleeve for French vinyl singleSingle by Led Zeppelinfrom the album Led Zeppelin IV B-sideMisty Mountain HopReleased2 December 1971 (1971-12-02) (US)StudioIsland Studios (London)[1]Genre Hard rock[2][3][4] blues rock[5] Length4:55LabelAtlanticSongwriter(s) John Paul Jones Jimmy Page Robert Plant Producer(s)Jimmy PageLed Zeppelin singles chron...

Bretagne Rendah (bahasa Breton: Breizh-Izel; Prancis: Basse-Bretagne) mencakup wilayah Bretagne di sebelah barat Ploërmel, tempat di mana bahasa Breton dituturkan, dan wilayah yang masih mempraktikkan budaya tradisional Keltik. Nama ini berkebalikan dengan Bretagne Tinggi, wilayah timur Bretagne, yang didominasi oleh budaya Roman. Dengan warna-warna, Bretagne Rendah, tempat bahasa Breton dituturkan; warna abu-abu adalah Bretagne Tinggi, yang menuturkan bahasa Gallo.

American nonprofit organization Harlem Children's Zone, Inc.Founded1990FounderGeoffrey CanadaFocusCombating effects of poverty; improving child and parent educationLocationNew York CityArea served HarlemMethodDonationsKey peopleGeoffrey Canada, President and first CEO, Kwame Owusu-Kesse, current CEO[1]Websitehcz.org Harlem Children's Zone and Promise Academy The Harlem Children's Zone (HCZ) is a nonprofit organization for children and families living in Harlem, providing free support ...

ąÜčĆąĄą╝ąĮąĖąĄą▓ą░čÅ ą┤ąŠą╗ąĖąĮą░ą░ąĮą│ą╗. Silicon Valley ą”ąĄąĮčéčĆ ą│ąŠčĆąŠą┤ą░ ąĪą░ąĮ-ąźąŠčüąĄ, ąĮą░ąĘčŗą▓ą░ąĄą╝ąŠą│ąŠ čüč鹊ą╗ąĖčåąĄą╣ ąÜčĆąĄą╝ąĮąĖąĄą▓ąŠą╣ ą┤ąŠą╗ąĖąĮčŗ ąĀą░čüą┐ąŠą╗ąŠąČąĄąĮąĖąĄ 37┬░22ŌĆ▓39ŌĆ│ čü. čł. 122┬░04ŌĆ▓03ŌĆ│ ąĘ. ą┤.HGą»O ąĪčéčĆą░ąĮą░ ąĪą©ąÉ ą©čéą░čéąÜą░ą╗ąĖč乊čĆąĮąĖčÅ ąÜčĆąĄą╝ąĮąĖąĄą▓ą░čÅ ą┤ąŠą╗ąĖąĮą░ ą£ąĄą┤ąĖą░čäą░ą╣ą╗čŗ ąĮą░ ąÆąĖą║ąĖčüą║ą╗ą░ą┤ąĄ ąŻ čŹč鹊ą│ąŠ č鹥čĆą╝ąĖąĮą░ čüčāčēąĄčüčéą▓čāčÄčé ąĖ ą┤čĆčāą│ąĖąĄ ąĘąĮą░č湥ąĮąĖč...

ALIMANAKA Taona 7 ŌĆó 8 ŌĆó 9 ŌĆó 10 ŌĆó 11 ŌĆó 12 ŌĆó 13 10 Taona -20 ŌĆó -10 ŌĆó 0 ŌĆó 10 ŌĆó 20 ŌĆó 30 ŌĆó 40 100 taona -300 ŌĆó -200 ŌĆó -100 ŌĆó 0 ŌĆó 100 ŌĆó 200 ŌĆó 300 1000 taona -3000 ŌĆó -2000 ŌĆó -1000 ŌĆó 0 ŌĆó 1000 - 2000 ŌĆó 3000 10 Amin'ny kalandrie hafa kalandrie Gregoriana 10 X Ab urbe condita 763 kalandrie Armenianina N/A Kalandrie sinoa 2706ŌĆō2707 Calendario ebreo 3770ŌĆō3771 Kalandrie hindoa~ Vikram Samvat~ Shaka Samvat< 65ŌĆō66N/A Kalandrie persana 612 B...