Kyriarchy

|

Read other articles:

Империя Хань. Армия империи Хань — военный аппарат китайской империи с 202 г. до н. э. по 220 год н. э. Содержание 1 Организация 1.1 Рекрутирование и обучение 1.2 Профессиональная и полу-профессиональная армии 1.3 Офицеры 1.4 Логистика и снабжение 1.5 Упадок 2 Вооружение ...

Anwar SanusiSekretaris Jenderal Kementerian Ketenagakerjaan Republik IndonesiaPetahanaMulai menjabat 28 Agustus 2020PresidenJoko Widodo Informasi pribadiLahir17 November 1968 (umur 55)Ponorogo, IndonesiaSuami/istriIstiqomahAnakHanief Mumtazul AnwarHasbullah Abimanyu AnwarLazuardi Ramadhan AnwarAlma materUniversitas Gajah Mada Saitama University National Graduate Institute for Policy StudiesSunting kotak info • L • B Prof. Drs. Anwar Sanusi, MPA, Ph.D. (lahir 17 November...

Soncin Rechtsform Gründung 1899 Auflösung 1902 Sitz Poissy Leitung Louis Soncin, Jean-Pierre Grégoire Branche Automobilhersteller Soncin Quadricycle von 1901 in der Cité de l’Automobile – Musée National – Collection Schlumpf Soncin war ein französischer Hersteller von Automobilen.[1][2][3] In der Literatur gibt es auch die Schreibweise Sonçin.[1][2] Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Unternehmensgeschichte 2 Fahrzeuge 3 Literatur 4 Weblinks 5 Einzelnachw...

オフェク重装甲兵員輸送車Ofek Heavy Armored Personnel Carrier 種類 装甲兵員輸送車原開発国 イスラエル運用史配備先 イスラエル国防軍開発史開発期間 2015年[1]諸元重量 ~ 60 t[1]全長 ~ 7.45 m[1]全幅 ~ 3.7 m[1]全高 ~ 2.7 m[1]要員数 2名 + 10名[1] 主兵装 FN MAG 7.62mm機関銃×1[1]エンジン コンチネンタル AVDS-1790-6A[1]ディーゼルエンジン、出...

Departments of the government of Argentina Politics of Argentina Executive President (List) :Alberto Fernández Vice President :Cristina Fernández de Kirchner Ministries Legislative Senate (List) Chamber of Deputies (List) Judiciary Supreme Court Attorney General Council of Magistracy of the Nation Law Constitution Human rights LGBT rights Administrative divisions Provinces Governors Legislatures Departments Recent elections Presidential: 2011201520192023 Legislative: 20152017201920212023 Po...

يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (فبراير 2016) السينما في الإمبراطورية الروسية تقريبا تغطي الفترة ما بين 1907 و1920، وهي الفترة التي أنشئت من أجلها بنية تح�...

American football player and sports coach (1880–1963) Alpha BrumageBrumage pictured in The Bomb 1913, VMI yearbookBiographical detailsBorn(1880-03-16)March 16, 1880Mitchell County, Kansas, U.S.DiedMarch 11, 1963(1963-03-11) (aged 82)San Antonio, Texas, U.S.Playing careerFootball1901–1903Kansas Position(s)FullbackCoaching career (HC unless noted)Football1904–1907Ottawa1908–1909William Jewell1910Nebraska State Normal1911–1912VMI1913–1914KentuckyBasketball1908–1910William Jewe...

Katharina NuttallBackground informationBorn (1972-07-14) 14 July 1972 (age 51)OriginDrammen, NorwayGenresRock, pop, alternativeOccupation(s)Artist, film composer, music producerLabelsFrances Records / Bonnier Amigo / Cargo Records /NovotonWebsitekatharinanuttall.comMusical artist Katharina Nuttall (born 14 July 1972) is an artist, film composer and music producer who was born in Drammen, Norway. Nuttall lives in Stockholm, Sweden but is a Norwegian citizen with a Norwegian mother and a f...

2021 film directed by Mikey Alfred North HollywoodFilm posterDirected byMikey AlfredWritten byMikey AlfredProduced by Mikey Alfred Yusef Chabayta Andrew Chennisi Mimi Valdes Malcolm Washington Pharrell Williams Samuel McIntosh Starring Ryder McLaughlin Vince Vaughn Miranda Cosgrove CinematographyAyinde AndersonEdited byAlex TsagamilisDistributed byIllegal CivilizationRelease date March 26, 2021 (2021-03-26) Running time93 minutesCountryUnited StatesLanguageEnglish North Hollywo...

この項目では、大長編ドラえもんの作品および1986年に公開された映画について説明しています。2011年に公開された映画については「ドラえもん 新・のび太と鉄人兵団 〜はばたけ 天使たち〜」をご覧ください。 ドラえもん > 大長編 > のび太と鉄人兵団 ドラえもん > 映画 > 大長編 > のび太と鉄人兵団 ドラえもん のび太と鉄人兵団(連載) ...

Canadian video game developer Hothead Games Inc.TypePrivateIndustryVideo gamesFounded2006; 17 years ago (2006)FoundersSteve BocskaVlad CeraldiJoel DeYoungHeadquartersVancouver, CanadaArea servedWorldwideKey peopleIan Wilkinson (President and CEO)Websitehotheadgames.com Hothead Games Inc. is an independent Canadian video game developer based in Vancouver. History The studio was founded in 2006 by Steve Bocska, Vlad Ceraldi and Joel DeYoung, all three of which were formerly em...

This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Minna Tanoshiku – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) 1982 studio album by Shonen KnifeMinna TanoshikuStudio album by Shonen KnifeReleased1982StudioStudio One and Yamaro ClubGenrePop punk, post ...

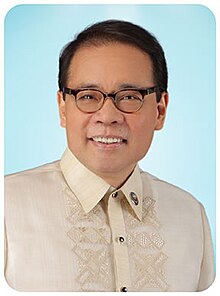

Filipino politician In this Philippine name, the middle name or maternal family name is Villanueva and the surname or paternal family name is Puno. Roberto Villanueva PunoDeputy Speaker of the House of Representatives of the PhilippinesIncumbentAssumed office July 25, 2022SpeakerMartin RomualdezIn officeJuly 22, 2019 – June 1, 2022SpeakerAlan Peter CayetanoLord Allan VelascoIn officeJune 30, 2013 – June 30, 2016SpeakerFeliciano Belmonte Jr.Member of the Phil...

German politician Daniel Billig (German politician) Daniel Billig (born 02 June 1970) is a German politician for the Alliance '90/The Greens and since 2018 member of the Abgeordnetenhaus of Berlin, the state parliament of Berlin. Politics Billig was born 1970 in the West German town of Monschau and studied[clarification needed] at the Free University of Berlin. Billig became member of the Abgeordnetenhaus in 2018.[1] References ^ Beikler, Sabine (December 16, 2017). Bayram und...

X-5англ. Bell X-5 Тип экспериментальный самолёт Разработчик Bell Aircraft Производитель Bell Aircraft Первый полёт 20 июня 1951 года Начало эксплуатации 1958 Конец эксплуатации декабрь 1958 года Статус музейный экспонат Эксплуатанты ВВС СШАНАСА Единиц произведено 2 Базовая модель Messerschmitt P.1...

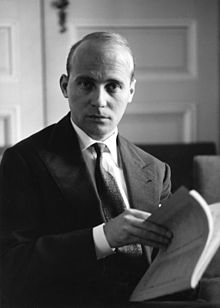

Opera by Hans Werner Henze Elegy for Young LoversElegie für junge LiebendeOpera by Hans Werner HenzeThe composer in 1960Librettist W. H. Auden Chester Kallman Premiere20 May 1961 (1961-05-20)Schlosstheater Schwetzingen Elegy for Young Lovers (German: Elegie für junge Liebende) is an opera in three acts by Hans Werner Henze to an English libretto by W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman. Background The opera was first performed in a German translation by Louis, Prince of Hesse and b...

TransmetalBackground informationOriginYurecuaro, Michoacan, MexicoGenresThrash metal, death metalYears active1987–presentWebsitetransmetalmexico.comMusical artist Transmetal is an extreme metal band formed in Ciudad Azteca, Ecatepec, Mexico in 1987 by brothers Javier, Juan, and Lorenzo Partida. They are known as one of the most important metal bands in Latin America.[1] Their most well known song is Killers from the Desear un Funeral EP (1989), which is a cover of French band Ki...

1953 film Hit ParadeDirected byErik OdeWritten byHans Fritz KöllnerAldo von PinelliProduced byHeinz-Joachim EwertStarringGermaine DamarWalter GillerNadja TillerCinematographyRichard AngstEdited byHermann LeitnerWolfgang WehrumMusic byFred FreedHeino GazeMichael JaryPeter KreuderProductioncompaniesHerzog FilmMelodie FilmDistributed byHerzog FilmRelease date 3 November 1953 (1953-11-03) Running time100 minutesCountryWest GermanyLanguageGerman Hit Parade (German: Schlagerparade) ...

German politician Wolfgang BörnsenBörnsen in 2009Member of the BundestagIn office18 February 1987 – 22 October 2013Preceded byHarm DallmeyerSucceeded bySabine Sütterlin-WaackConstituencyFlensburg – Schleswig Personal detailsNationalityGermanPolitical partyChristian Democratic UnionChildrenFourAlma materPädagogische Akademie KielOccupationTeacher Wolfgang Börnsen (born 26 April 1942) is a German politician and member of the CDU, which he joined in 1967. He was born in Flensbu...

British bishop (1798–1882) Alfred Ollivant Alfred Ollivant monument in Llandaff Cathedral Alfred Ollivant (1798 – 16 December 1882) was an academic who went on to become Bishop of Llandaff. Born in Manchester, he was educated at St Paul's School and Trinity College, Cambridge.[1] He won the Tyrwhitt Hebrew scholarship in 1822 and was elected to a fellowship at Trinity College. In 1827, he was appointed the first vice-principal of St David's College, Lampeter. Whilst at Lampete...