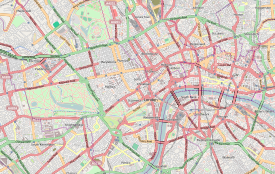

Palace of Whitehall

| |||||||||||||||||

Read other information related to :Palace of Whitehall/

Palace ʻIolani Palace Oguzhan Presidential Palace Heian Palace Republican Palace, Khartoum Heliopolis Palace Schön Palace Mikhailovsky Palace Blenheim Palace Boukoleon Palace Sarvestan Palace Buçaco Palace Buckingham Palace Crystal Palace F.C. Ōmiya Palace Tokyo Imperial Palace Diocletian's Palace Schönbrunn Palace Crystal Palace, London Fulham Palace Peterhof Palace Krasiński Palace The Crystal Palace Palace of the Shirvanshahs Tyzenhauz Palace National Palace Museum Apostolic Palace Mysore Palace Royal Palace, Oslo Brühl Palace, Warsaw Palace Museum Stockholm Palace Çırağan Palace …

Malacañang Palace Palace of Aachen Vileišis Palace St James's Palace Livadia Palace Slushko Palace Abdeen Palace National Palace (Mexico) Connor Palace Fanshawe Palace Heijō Palace Alexandra Palace Winter Palace Egmont Palace Brühl palace Holyrood Palace Dolmabahçe Palace Khaplu Palace Palace of Yashbak Lateran Palace Royal Palace of Amsterdam Dhenkanal Palace Epang Palace Caravan Palace Summer Palace (Rastrelli) Sobański Palace Royal Palace of Caserta Moti Bagh Palace Saffron Palace Mariinsky Palace Bakhchysarai Palace Palace of Monimail Palace Cinemas (Australia) Narayanhiti Palace Palace of Mafra Basheer Bagh Palace Daming Palace Royal Palace, Wrocław Archbishop's Palace Golestan Palace Catherine Palace Mukden Palace Saxon Palace Anand Bagh Palace Topkapı Palace Palace Theatre Radziwiłł Palace (Vilnius) Doge's Palace Academy Palace List of palaces Sintra National Palace Palace Station United Palace Presidential palace Tauride Palace Ruhyýet Palace Palace of the Porphyrogenitus Sapieha Palace, Vilnius Palace of Whitehall Pearl Palace Mattancherry Palace Buckingham Palace Garden Kilimanoor Palace National Palace (Haiti) Estaus Palace Al-Azm Palace Abbot's Palace (Oliwa)

Read other articles:

Lasionycta benjamini Lasionycta benjamini benjamini Lasionycta benjamini medaminosaTaxonomíaReino: AnimaliaFilo: ArthropodaClase: InsectaOrden: LepidopteraFamilia: NoctuidaeTribu: HadeniniGénero: LasionyctaEspecie: L. benjaminiHill, 1927[editar datos en Wikidata] Lasionycta benjamini es una especie de mariposa nocturna de la familia Noctuidae. Se encuentra en la Sierra Nevada de California y en las montañas de Nevada y Colorado. Su hábitat son los bosques montañosos de con

Сувлакі Країна походження Греція Сувлакі у Вікісховищі Набір для самостійного приготування «сувлакі в піті» Сувла́кі (грец. σουβλάκι) або сувла́кія — популярна грецька закуска, яка складається з маленьких шматочків м'яса та овочів, підсмажених на грилі. Зазвича

Berikut ini merupakan media massa yang ada di wilayah DKI Jakarta. Surat kabar Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta memiliki beberapa surat kabar di antara: Nama Jenis Perusahaan Bahasa Koran Sindo Nasional Media Nusantara Citra Indonesia Investor Daily B Universe Kompas KG Media Koran Tempo Tempo Media Group Bisnis Indonesia Bisnis Indonesia Group Media Indonesia Media Group Kontan KG Media Koran Jakarta Berita Nusantara Republika MahakaX The Jakarta Post Bina Media Tenggara Inggris Indonesia Shang Ba…

Одеський національний художній музей 46°29′36″ пн. ш. 30°43′43″ сх. д. / 46.49340000002777629° пн. ш. 30.72880000002777834° сх. д. / 46.49340000002777629; 30.72880000002777834Координати: 46°29′36″ пн. ш. 30°43′43″ сх. д. / 46.49340000002777629° пн. ш. 30.72880000002777834° сх. д. …

This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Siege of Hulst 1645 – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (September 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Siege of HulstPart of Eighty Years' WarThe siege and capture of Hulst in 1645 by Hendrick de Meijer.Date7 October – 4 November 1645Location…

Shanghai Pudong Development Bank Co. Ltd上海浦东发展银行JenisPerusahaan publikKode emitenSSE: 600000IndustriPerbankan, KeuanganDidirikan1993KantorpusatShanghai, Republik Rakyat TiongkokTokohkunciJi Xiaohui, KetuaProdukJasa keuanganPendapatann/aLaba bersihAS$ 418.750.000 (2006)[1]Karyawan31000Situs webwww.spdb.com.cn/ Shanghai Pudong Development Bank Hanzi: 上海浦东发展银行 Pinyin: Shànghǎi Pǔdōng Fāzhǎn Yínháng Alih aksara Mandarin - Hanyu Pinyin: Shànghǎi Pǔd

Police Service of Bihar This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Bihar Police – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Bihar PoliceBihar Police Official LogoCommon nameBihar PoliceAbbreviationBPMottoउत्कृष्टता…

Dieser Artikel oder nachfolgende Abschnitt ist nicht hinreichend mit Belegen (beispielsweise Einzelnachweisen) ausgestattet. Angaben ohne ausreichenden Beleg könnten demnächst entfernt werden. Bitte hilf Wikipedia, indem du die Angaben recherchierst und gute Belege einfügst. Power Metal ist ein Metal-Subgenre hauptsächlich europäischen Ursprungs.[1] Vor der europäischen Strömung entstand auch ein US-amerikanischer Metal-Stil gleichen Namens, der jedoch nicht die Popularität des e…

Video game series Like a Dragon and Ryu Ga Gotoku redirect here. For the seventh mainline game in this series, see Yakuza: Like a Dragon. For the film based on the first game, see Like a Dragon (film). For the studio known for its development, see Ryu Ga Gotoku Studio. For the first video game in the series, see Yakuza (video game). Video game seriesLike a DragonOriginal international logo (top); and original Japanese logo (bottom)Genre(s)Action-adventure, beat 'em up, role-playingDeveloper(s)Ry…

Japanese manga series B. IchiCover of the first volume of B. IchiB壱GenreFantasy[1] MangaWritten byAtsushi OhkuboPublished byGangan ComicsEnglish publisherNA: Yen PressMagazineMonthly Shōnen GanganDemographicShōnenOriginal run2001 – 2002Volumes4 B. Ichi (B壱, B1) is a Japanese manga written and illustrated by Atsushi Ohkubo and serialized in Monthly Shōnen Gangan from 2001 to 2002. Set in the city of Toykyo, the series focuses on humans known as Dokeshi, whose abilities …

У Вікіпедії є статті про інші значення цього терміна: Айдар. 24-й окремий штурмовий батальйон «Айдар» Нарукавний знак батальйонуЗасновано 3 травня 2014Країна УкраїнаВид Сухопутні військаТип Механізовані військаРоль штурмовий батальйонЧисельність понад 800 осібУ с�…

Bakery chain in Singapore This article is about the Singaporean bakery chain. For other uses, see Bengawan Solo. A Bengawan Solo store at The Arcade Bengawan Solo is a Singaporean bakery chain. It has 45 outlets islandwide with a factory at 23 Woodlands Link. The bakery is known for making and selling Indonesian style kue, buns, cakes, cookies and mooncakes due to the fact that the owner and founder, Anastasia Liew, is an Indonesian who migrated to Singapore from Palembang in early 1970s. All pr…

Song by Russ featuring BIA Best on EarthSingle by Russ featuring Biafrom the album Shake the Snow Globe ReleasedOctober 17, 2019Length2:40LabelDiemonColumbiaSongwriter(s)Russell VitaleMatthew SamuelsJahaan SweetBianca LandrauJonathan SmithCraig LoveDonnell PrinceJamal GlazeLaMarquis JeffersonLawrence EdwardsProducer(s)Boi-1daSweetRuss singles chronology Old Days (2019) Best on Earth (2019) Give Up (2020) Bia singles chronology One Minute Run(2019) Best on Earth(2019) Free Bia (1st Day Ou…

Temple Dinsley redirects here. For the former country house, see Princess Helena College. Human settlement in EnglandPrestonSt Martin's Church, PrestonPrestonLocation within HertfordshirePopulation420 (2011 Census)[1]OS grid referenceTL181247Civil parishPrestonDistrictNorth HertfordshireShire countyHertfordshireRegionEastCountryEnglandSovereign stateUnited KingdomPost townHitchinPostcode districtSG4Dialling code01462PoliceHertfordshireFireHertfordshireA…

Josina Machel Hospital Lucrécia Paím Maternity Hospital Our Lady of Peace Hospital This is a list of hospitals in Angola. As of 2019[update] there are a total of 1,575 medical facilities in Angola.[1][2] Hospitals The hospitals in the table below shows the name, location, affiliation, and number of licensed beds. Only the most notable hospitals in Angola are listed. The best hospitals are located in the country's capital city, Luanda. The largest number of medical facil…

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article is an orphan, as no other articles link to it. Please introduce links to this page from related articles; try the Find link tool for suggestions. (May 2015) This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and rem…

Hospital in Ontario, CanadaUniversity HospitalLondon Health Sciences CentreUniversity Hospital. Main entrance.Location in OntarioGeographyLocationLondon, Ontario, CanadaCoordinates43°00′45″N 81°16′30″W / 43.0125°N 81.275°W / 43.0125; -81.275OrganizationCare systemPublic Medicare (Canada)TypeTeachingAffiliated universitySchulich School of Medicine & DentistryServicesEmergency departmentLevel I trauma centerBeds418[1]SpecialityMultipleHelipadTC LID: …

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Ekstraklasa – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)Professional association football league in Poland Football leagueEkstraklasaOrganising bodyEkstraklasa SAFounded4 December 1926;…

Álvaro PachónDatos personalesNacimiento Bogotá30 de noviembre de 1945País Colombia ColombiaNacionalidad(es) ColombianaCarrera deportivaDeporte CiclismoDisciplina RutaTrayectoria Equipos amateur 1964-19681969-19701971-1975197619771978-197919801981 CundinamarcaPierceSingerManzana de EvaLibreta de PlataLotería de CundinamarcaDroguería YanethVinícola Los Frayles Títulos Vuelta a Colombia 1971 Clásico RC…

Department in ArgentinaSan Pedro Partido de San PedroDepartment Coat of armslocation of San Pedro Partido in Buenos Aires ProvinceCoordinates: 33°40′S 59°40′W / 33.667°S 59.667°W / -33.667; -59.667CountryArgentinaEstablishedDecember 30, 1784Founded by?SeatSan PedroGovernment • MayorCecilio Salazar (Fe Party)Area • Total1,322 km2 (510 sq mi)Population • Total55,234 • Density42/km2 (110/sq mi)Demony…