Anarchism in Nigeria

|

Read other articles:

ўДўЕЎєЎІўЖўН Ў£ЎЃЎ±ўЙЎМ ЎЈЎІўДЎє ЎІўДЎ≠ЎѓЎ®Ў© (Ў™ўИЎґўКЎ≠). ЎІўДЎ≠ЎѓЎ®Ў© - ўЕўЖЎЈўВЎ© Ў≥ўГўЖўКЎ© - Ў™ўВЎ≥ўКўЕ Ў•ЎѓЎІЎ±ўК ЎІўДЎ®ўДЎѓ ЎІўДЎ£Ў±ЎѓўЖ ЎІўДўЕЎ≠ЎІўБЎЄЎ© ўЕЎ≠ЎІўБЎЄЎ© ЎІўДўГЎ±ўГ ўДўИЎІЎ° ўДўИЎІЎ° ЎІўДўЕЎ≤ЎІЎ± ЎІўДЎђўЖўИЎ®ўК ўВЎґЎІЎ° ўВЎґЎІЎ° ЎІўДўЕЎ≤ЎІЎ± ЎІўДЎђўЖўИЎ®ўК ЎІўДЎ≥ўГЎІўЖ ЎІўДЎ™ЎєЎѓЎІЎѓ ЎІўДЎ≥ўГЎІўЖўК 344 ўЖЎ≥ўЕЎ© (Ў•Ў≠ЎµЎІЎ° 2015) вАҐ ЎІўДЎ∞ўГўИЎ± 173 вАҐ ЎІўДЎ•ўЖЎІЎЂ 171 вАҐ ЎєЎѓЎѓ ЎІўДЎ£Ў≥Ў± 73 ўЕЎєўДўИўЕЎІЎ™ Ў£ЎЃ

–£ –Т—Ц–Ї—Ц–њ–µ–і—Ц—Ч —Ф —Б—В–∞—В—В—Ц –њ—А–Њ —Ц–љ—И—Ц –≥–µ–Њ–≥—А–∞—Д—Ц—З–љ—Ц –Њ–±вАЩ—Ф–Ї—В–Є –Ј –љ–∞–Ј–≤–Њ—О –С–µ–≤–µ—А–ї—Ц. –Ь—Ц—Б—В–Њ –С–µ–≤–µ—А–ї—Ц–∞–љ–≥–ї. Beverly –Ъ–Њ–Њ—А–і–Є–љ–∞—В–Є 40¬∞03вА≤53вА≥ –њ–љ. —И. 74¬∞55вА≤18вА≥ –Ј—Е. –і. / 40.06480000002777331¬∞ –њ–љ. —И. 74.92190000002777595¬∞ –Ј—Е. –і. / 40.06480000002777331; -74.92190000002777595–Ъ–Њ–Њ—А–і–Є–љ–∞—В–Є: 40¬∞03вА≤53вА≥ –њ–љ. —И. 74¬∞55вА≤18вА≥ –Ј—Е...

Permainan Minesweeper yang sudah selesai. Minesweeper adalah permainan komputer untuk satu pemain. Tujuan permainan ini adalah untuk membersihkan lahan permainan tanpa mengenai ranjau. Permainan ini telah ditulis kembali untuk hampir semua platform. Versi yang paling terkenal adalah versi Minesweeper untuk Windows, yang disertakan dalam Windows 3.1 keatas. Permainan Permainan ini dilakukan dengan cara membuka kotak pada grid, umumnya dengan melakukan klik pada tetikus. Jika kotak yang terbuka...

Skjaldbrei√∞ur El Skjaldbrei√∞ur visto desde √ЮingvellirCordillera Tierras Altas de IslandiaCoordenadas 64¬∞24вА≤36вА≥N 20¬∞45вА≤44вА≥O / 64.41, -20.762222Localizaci√≥n administrativaPa√≠s IslandiaDivisi√≥n Bl√°sk√≥gabygg√∞Caracter√≠sticas generalesTipo Volc√°n en escudoAltitud 1060Geolog√≠aEra geol√≥gica 9.000 a√±osObservatorio NordvulkMapa de localizaci√≥n Skjaldbrei√∞ur Ubicaci√≥n en Islandia. [editar datos en Wikidata] Skjaldbrei√∞ur (i. e. 'escudo ancho' en island

Eobalaenoptera–Я–µ—А—Ц–Њ–і —Ц—Б–љ—Г–≤–∞–љ–љ—П: —Б–µ—А–µ–і–љ—Ц–є –Љ—Ц–Њ—Ж–µ–љ –°–Ї–µ–ї–µ—В, –Њ–Ї—А—Г–≥ –Ъ–µ—А–Њ–ї–∞–є–љ, –Т—Ц—А–і–ґ–Є–љ—Ц—П –С—Ц–Њ–ї–Њ–≥—Ц—З–љ–∞ –Ї–ї–∞—Б–Є—Д—Ц–Ї–∞—Ж—Ц—П –¶–∞—А—Б—В–≤–Њ: –Ґ–≤–∞—А–Є–љ–Є (Animalia) –Ґ–Є–њ: –•–Њ—А–і–Њ–≤—Ц (Chordata) –Ъ–ї–∞–і–∞: –°–Є–љ–∞–њ—Б–Є–і–Є (Synapsida) –Ъ–ї–∞—Б: –°—Б–∞–≤—Ж—Ц (Mammalia) –†—П–і: –Я–∞—А–љ–Њ–Ї–Њ–њ–Є—В–љ—Ц (Artiodactyla) –Ж–љ—Д—А–∞—А—П–і: –Ъ–Є—В–Њ–њ–Њ–і—Ц–±–љ—Ц (Cetacea) –Я–∞—А–≤–Њ—А—П–і: –Ъ–Є—В–Њ–≤–Є–і—Ц (Mysticeti) –Э–∞–і—А–Њ–і–...

ўЗЎ∞ўЗ ЎІўДўЕўВЎІўДЎ© ўКЎ™ўКўЕЎ© Ў•Ў∞ Ў™ЎµўД Ў•ўДўКўЗЎІ ўЕўВЎІўДЎІЎ™ Ў£ЎЃЎ±ўЙ ўВўДўКўДЎ© ЎђЎѓўЛЎІ. ўБЎґўДўЛЎІЎМ Ў≥ЎІЎєЎѓ Ў®Ў•ЎґЎІўБЎ© ўИЎµўДЎ© Ў•ўДўКўЗЎІ ўБўК ўЕўВЎІўДЎІЎ™ ўЕЎ™ЎєўДўВЎ© Ў®ўЗЎІ. (ЎѓўКЎ≥ўЕЎ®Ў± 2020) ўБўДўИЎ±ўКўЖ ўБЎІЎ®ўКЎІўЖ ўЕЎєўДўИўЕЎІЎ™ ЎіЎЃЎµўКЎ© ЎІўДўЕўКўДЎІЎѓ 23 Ў£ЎЇЎ≥ЎЈЎ≥ 1974 (49 Ў≥ўЖЎ©) Ў≥ЎІЎ™ўИ ўЕЎІЎ±ўК ўЕЎ±ўГЎ≤ ЎІўДўДЎєЎ® ўЕўЗЎІЎђўЕ ЎІўДЎђўЖЎ≥ўКЎ© Ў±ўИўЕЎІўЖўКЎІ ўЕЎєўДўИўЕЎІЎ™ ЎІўДўЖЎІЎѓўК ЎІўДўЖЎІЎѓўК ЎІўДЎ≠ЎІўДўК Ў±ўКЎ®ўЖЎ≥ўКЎІ Ў™ўКўЕўКЎіўИЎІЎ±ЎІ (ўЕ

Japanese samurai This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Suzuki Magoichi вАУ news ¬Ј newspapers ¬Ј books ¬Ј scholar ¬Ј JSTOR (December 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) In this Japanese name, the surname is Suzuki. Suzuki Magoichi Suzuki Magoichi (йИіжЬ®е≠ЂдЄАгАБйИіжЬ®е≠ЂеЄВ), bett...

United States: Kentucky / Louisville TemplateвАСclass United States portalThis template is within the scope of WikiProject United States, a collaborative effort to improve the coverage of topics relating to the United States of America on Wikipedia. If you would like to participate, please visit the project page, where you can join the ongoing discussions. Template Usage Articles Requested! Become a Member Project Talk Unreferenced BLPs Alerts United StatesWikipedia:WikiProject United StatesT...

This article relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this article by adding secondary or tertiary sources. Find sources: Augusta University Medical Center вАУ news ¬Ј newspapers ¬Ј books ¬Ј scholar ¬Ј JSTOR (January 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Hospital in Georgia, United StatesAugusta University HealthGeographyLocationAugusta, Georgia, United StatesOrganizationAffiliated universityAugusta University,...

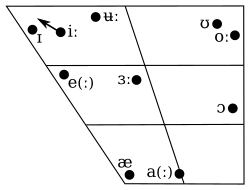

Sound system of Australian English This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA ¬І Brackets and transcription delimiters. Speech example A man with a general Australian accent reading aloud part of the Australia Wikipedia article. Problems playing this file? See media help. Speech example A man fr...

1997 single by Edyta Górniak One and One is a song written by Billy Steinberg, Rick Nowels and Marie-Claire D'Ubaldo. The song was performed by Edyta Górniak. It was covered by Robert Miles (feat. Maria Nayler) in 1996. Edyta Górniak version One & OneEuropean CD maxi-singleSingle by Edyta Górniakfrom the album Edyta Gorniak Released1997Length3:38LabelEMISongwriter(s)Billy Steinberg, Marie-Claire D'Ubaldo, Rick NowelsProducer(s)Christopher NeilEdyta Górniak singles chronology When...

Sungai GombakSungai Gombak (kiri) bertemu dengan Sungai Klang (kanan) di Kuala Lumpur.LokasiNegaraSelangor dan Kuala Lumpur, MalaysiaCiri-ciri fisikMuara sungaiSungai Klang Sungai Gombak adalah nama sungai yang mengalir melalui Selangor dan Kuala Lumpur di Malaysia. Sungai ini merupakan anak Sungai Kelang. Tempat sungai ini bertemu dengan Sungai Klang merupakan asal nama Kuala Lumpur. Masjid Jamek terletak di pinggir muara tersebut. Sungai Gombak merupakan salah satu dari dua sungai penyebab ...

American physician Steven H. Miles is an American doctor, author, and professor of medicine who has published on ethically topics relating to medicine and the use of torture.[1][2] Miles is a practicing physician and Professor of Medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical School[3] and is a member of its Center for Bioethics. He is a recipient of the Distinguished Service Award of the American Society of Bioethics and Humanistics. Miles is a fellow of the Hastings...

Sim√≥n Bol√≠var, Freiheitsheld mehrerer s√Љdamerikanischer Staaten Mahatma Gandhi, hier auf dem Salzmarsch, erk√§mpfte gewaltfrei die Unabh√§ngigkeit Indiens. Unabh√§ngigkeitsdenkmal in Litauen Staatliche Unabh√§ngigkeit bezeichnet das Recht eines Staatswesens, seine Entscheidungen unabh√§ngig von Bevormundung durch einen anderen Staat zu treffen. Damit ist sie juristisch dasselbe wie v√ґlkerrechtliche Souver√§nit√§t; trotzdem sind beide Begriffe nicht synonym. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Souver√§ni...

Far-right anti-Islam movement Counter-jihad, also known as the counter-jihad movement,[1] is a self-titled political current loosely consisting of authors, bloggers, think tanks, street movements and campaign organisations all linked by beliefs that view Islam not as a religion but as an ideology that constitutes an existential threat to Western civilization. Consequently, counter-jihadists consider all Muslims as a potential threat, especially when they are already living within West...

Japanese actress (born 2001) The native form of this personal name is Yabuki Nako. This article uses Western name order when mentioning individuals. Nako YabukiзЯҐеРє е•Ие≠РYabuki in December 2023Born (2001-06-18) 18 June 2001 (age 22)Tokyo, JapanNationalityJapaneseOccupationActressYears active2005[1]вАУpresentAgentTwin PlanetMusical careerGenresJ-popK-popInstrument(s)VocalsYears active2013вАУ2023LabelsEMI Records[a]Off The Record[b]VernalossomFormerly of...

French writer (1946вАУ1988) Guy HocquenghemHocquenghem in 1983Born10 December 1946Boulogne-Billancourt, FranceDied28 August 1988(1988-08-28) (aged 41)Paris, FranceEra20th-century philosophyRegionWestern PhilosophySchoolContinental philosophy, queer theory Guy Hocquenghem (French: [ok…ЫћГ…°…Ыm]; 10 December 1946[1] вАУ 28 August 1988) was a French writer, philosopher, and queer theorist. Biography Hocquenghem was born in the suburbs of Paris and was educated at the Lyc√©e ...

This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Princes Park, Eastbourne вАУ news ¬Ј newspapers ¬Ј books ¬Ј scholar ¬Ј JSTOR (October 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) The Oval Princes Park in Eastbourne, East Sussex, England, is a 33-acre (13 ha) public park 1 mile (1.6 km) east of Eastbourne Tow...

For the 2010 film, see Manasara (film). Some town plans recommended in the 700 CE Manasara Sanskrit text on Hindu architecture[1][2][3] The MƒБnasƒБra, also known as Manasa or Manasara Shilpa Shastra, is an ancient Sanskrit treatise on Indian architecture and design.[4] Organized into 70 adhyayas (chapters) and 10,000 shlokas (verses),[5] it is one of many Hindu texts on Shilpa Shastra вАУ science of arts and crafts вАУ that once existed in 1st-millenni...

–Т —Б—В–∞—В—М–µ –љ–µ —Е–≤–∞—В–∞–µ—В —Б—Б—Л–ї–Њ–Ї –љ–∞ –Є—Б—В–Њ—З–љ–Є–Ї–Є (—Б–Љ. —А–µ–Ї–Њ–Љ–µ–љ–і–∞—Ж–Є–Є –њ–Њ –њ–Њ–Є—Б–Ї—Г). –Ш–љ—Д–Њ—А–Љ–∞—Ж–Є—П –і–Њ–ї–ґ–љ–∞ –±—Л—В—М –њ—А–Њ–≤–µ—А—П–µ–Љ–∞, –Є–љ–∞—З–µ –Њ–љ–∞ –Љ–Њ–ґ–µ—В –±—Л—В—М —Г–і–∞–ї–µ–љ–∞. –Т—Л –Љ–Њ–ґ–µ—В–µ –Њ—В—А–µ–і–∞–Ї—В–Є—А–Њ–≤–∞—В—М —Б—В–∞—В—М—О, –і–Њ–±–∞–≤–Є–≤ —Б—Б—Л–ї–Ї–Є –љ–∞ –∞–≤—В–Њ—А–Є—В–µ—В–љ—Л–µ –Є—Б—В–Њ—З–љ–Є–Ї–Є –≤ –≤–Є–і–µ —Б–љ–Њ—Б–Њ–Ї. (2 —Д–µ–≤—А–∞–ї—П 2015) Windows Thin PC –†–∞–Ј—А–∞–±–Њ—В—З–Є–Ї –Ъ–Њ—А–њ–Њ—А–∞—Ж–Є—П –Ь–...