Military sexual trauma |

Read other articles:

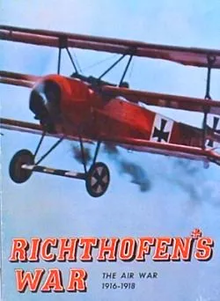

1973 WWI board wargame Richthofen's War, subtitled The Air War 1916–1918, is a board wargame published by Avalon Hill in 1973 that simulates aerial combat during World War I. Description Richthofen's War is a two-player game in which one player controls one or more German airplanes of the First World War, and the other player controls Allied aircraft.[1] Components The game box contains:[1] 22 x 24 mounted hex grid map of a section of the Western Front, including lines of tr...

Neighborhood book exchange nonprofit Little Free Library Ltd.A Little Free LibraryFounded2009 (2009)FounderTodd BolType501(c)(3) nonprofit organization[1]Tax ID no. 45-4043708[2]PurposeTo be a catalyst for building community, inspiring readers, and expanding book access for all through a global network of volunteer-led Little Free Libraries. [3]HeadquartersSt. Paul, MinnesotaExecutive DirectorGreig Metzger[4]Revenue (2021) $4,350,241[5]Expenses (20...

PausNikolaus IIIAwal masa kepausan25 November 1277Akhir masa kepausan22 Agustus 1280PendahuluYohanes XXIPenerusMartinus IVInformasi pribadiNama lahirGiovanni Gaetano OrsiniLahir1210/1220Roma, ItaliaMeninggal22 Agustus 1280Roma, Italia Nikolaus III, nama lahir Giovanni Gaetano Orsini (Roma, Italia, 1210/1220 – Roma, Italia, 22 Agustus 1280), adalah Paus Gereja Katolik Roma sejak 25 November 1277 sampai 22 Agustus 1280. lbs Paus Gereja Katolik Daftar paus grafik masa jabatan orang kudus Nama ...

PL.10 Role Carrier-borne reconnaissance aircraftType of aircraft National origin France Manufacturer Levasseur First flight Spring 1929 Introduction 1931 Primary user Aéronavale Number built 63 Levasseur PL.10 in flight Levasseur PL.101 The Levasseur PL.10 was a carrier-based reconnaissance aircraft developed in France in the late 1920s.[1] It was a conventional, single-bay biplane along similar lines to Levasseur's contemporary designs for the French navy, including a watertigh...

This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: National Movement Colombia – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) This article is part of a series on thePolitics ofColombia Government Constitution of Colombia Law Taxation Policy Executive Preside...

A Hindu mantra Om Namo Bhagavate Vāsudevaya in Devanagari Om Namo Bhagavate Vāsudevāya (listenⓘ) (Devanagari: ॐ नमो भगवते वासुदेवाय) lit. 'I bow to the Ultimate Reality, Vāsudeva' is one of the most popular Hindu mantras, and according to the Bhagavata tradition, the most important mantra in Vaishnavism.[1] It is called the Dvadasakshari Mantra,[2] or simply Dvadasakshari, meaning the twelve-syllable mantra, dedicated to Vish...

Westelijke Sahara De Katholieke Kerk in de Westelijke Sahara is een onderdeel van de wereldwijde Rooms-Katholieke Kerk, onder het geestelijk leiderschap van de paus en de curie in Rome. In 2004 waren ongeveer 110 (0,3%) van de 766.200 inwoners van de Westelijke Sahara lid van de Katholieke Kerk.[1] Het gebied bestaat uit een enkele apostolische prefectuur, namelijk de apostolische prefectuur Westelijke Sahara, dat direct onder de Heilige Stoel valt. Sinds 25 februari 2009 is er geen a...

Rainforest World Music FestivalBand gipsi Prancis membawakan lagu pada RWMF 2006JenisMusic festivalsTanggalPertengahan tahunLokasiKuching, Sarawak, Malaysia Kuching (1998–sekarang) Tahun aktif1998–sekarangPendiriRandy Raine- ReuschAnggaranRM 4 jutaSitus webrwmf.net Rainforest World Music Festival (RWMF), atau Festival Musik Hutan Hujan Dunia, adalah festival musik tahunan selama tiga hari untuk merayakan keberagaman musik dunia, yang diselenggarakan di Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia, dengan l...

Umbi pada Dentaria bulbifera Recup[1] atau umbi tunas atau bulbil (juga disebut sebagai bulbel, bulblet, dan/atau pup) adalah tanaman muda kecil yang direproduksi secara vegetatif dari tunas ketiak pada batang tanaman induk atau sebagai pengganti bunga pada perbungaan . [2] Tanaman muda ini adalah klon dari tanaman induk yang menghasilkannya—mereka memiliki materi genetik yang identik. [3] [4] [5] Pembentukan recup adalah salah satu bentuk reproduksi ...

Infotainment AwardsPenghargaan terkini: Infotainment Awards 2022DeskripsiApresiasi terhadap dunia InfotainmentLokasiJakarta, IndonesiaNegaraIndonesiaDiberikan perdana20 Januari 2012 (2012-01-20)Siaran televisi/radioSaluranSCTV Infotainment Awards adalah sebuah acara penghargaan yang diselenggarakan oleh Surya Citra Media untuk mengapresiasi selebritas infotainment serta artis yang terlibat, khususnya yang selama ini telah menjadi bagian dari SCTV dan memberi dampak positif bagi masyaraka...

Arai Helmet Tipo negocio y empresaForma legal Sociedad de responsabilidad limitadaFundación 1926Sede central Saitama, JapónSitio web www.araihelmet.com[editar datos en Wikidata] Este artículo o sección necesita referencias que aparezcan en una publicación acreditada.Este aviso fue puesto el 1 de julio de 2020. Arai Helmet es una empresa japonesa que diseña y fabrica cascos de motocicleta y automovilismo. Creada en 1926 por Hirotake Arai, en sus inicios se dedicaba a la fabrica...

Philips-developed system with digital audio on compact cassette Not to be confused with Digital Audio Tape. Digital Compact Cassette A Digital Compact Cassette sent to the readers of Q magazineMedia typeMagnetic cassette tapeEncodingPrecision Adaptive Sub-band Coding (MPEG-1 Audio Layer I)CapacityTheoretically 120 minutes; longest available tapes were 105 minutesWrite mechanismmulti-track stationary headDeveloped byPhilipsMatsushita ElectricUsageaudioExtended fromCompact Casset...

A. Geoffrey LeeInternational Commissioner of Scouts Australia A. Geoffrey Geoff Lee AM OAM (1928–2007) served as the International Commissioner of Scouts Australia, as well as the Vice-Chairman of the Asia-Pacific Scout Committee and then Vice Chairman of the Lord Baden-Powell Society Management Committee, and played a major role in the success of the 16th World Scout Jamboree. In 2001, Lee was awarded the 289th Bronze Wolf, the only distinction of the World Organization of the Scout Moveme...

2006 live album by IsisLive.04Live album by IsisReleasedMay 2006RecordedVarious datesGenrePost-metal, Sludge metal, Experimental metalLength63:38LabelSelf-released (CD)Robotic Empire (vinyl)(Robo 079)ProducerIsisIsis chronology Live.03(2005) Live.04(2006) In the Absence of Truth(2006) Live.04 is Isis's fourth live release and the first to be composed of recordings from several different sources and eras. Many of the tracks are from audience bootleg recordings, and as such do not sound...

This article is about the Colombian city. For other uses, see Santa Marta (disambiguation). You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Spanish. (December 2013) Click [show] for important translation instructions. Machine translation, like DeepL or Google Translate, is a useful starting point for translations, but translators must revise errors as necessary and confirm that the translation is accurate, rather than simply copy-pasting machine-tr...

Free and open-source virtual private network software OpenVPNOriginal author(s)James YonanDeveloper(s)OpenVPN project / OpenVPN Inc.Initial release13 May 2001; 22 years ago (2001-05-13)[1]Stable release2.6.8[2] (17 November 2023; 20 days ago (2023-11-17)) [±] Repositorygithub.com/OpenVPN Written inCPlatform Windows 7 or later[3] OS X 10.8 or later Android 4.0 or later[4] iOS 6 or later[5] Linux[6]...

この記事は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。(このテンプレートの使い方)出典検索?: 具志川バスターミナル – ニュース · 書籍 · スカラー · CiNii · J-STAGE · NDL · dlib.jp · ジャパンサーチ · TWL(2014年3月) 具志川バスターミナル(琉球バス�...

Masjid Agung Bantenمسجد بنتن الكبيرMasjid Agung Banten (2017)AgamaAfiliasi agamaIslam – SunniProvinsi BantenLokasiLokasiJl. Masjid Agung, Banten, Kec. Kasemen, Kota Serang, Banten 42-191Negara IndonesiaKoordinat6°2′10.356″S 106°9′17.388″E / 6.03621000°S 106.15483000°E / -6.03621000; 106.15483000Koordinat: 6°2′10.356″S 106°9′17.388″E / 6.03621000°S 106.15483000°E / -6.03621000; 106.15483000Arsitek...

Software company in United Kingdom AnimoCambridge Animation SystemsDeveloper(s)Cambridge Animation Systems Ltd.Initial release1992; 31 years ago (1992)Final release6.0 / 8 December 2004; 18 years ago (2004-12-08) Operating systemMicrosoft Windows, Mac OS X, SGI O2Type2D animation softwareLicenseProprietary Cambridge Animation Systems was a British software company that developed a traditional animation software package called Animo and is now part of Canadi...

For the 1993 Czech film, see Krvavý román. 2013 Indian filmHorror StoryTheatrical release posterDirected byAyush RainaWritten byVikram BhattMohan AzadSukhmani Sadana (dialogues)Produced byASA Productions and Enterprises Pvt. Ltd.StarringKaran KundraRadhika MenonNishant Singh MalkaniRavish DesaiHasan ZaidiAparna BajpaiNandini VaidSheetal SinghCinematographyGargey trivediEdited byKuldip MehanMusic byAmar MohileProductioncompaniesASA Production and Enterprises Pvt Ltd.Distributed byASA Product...