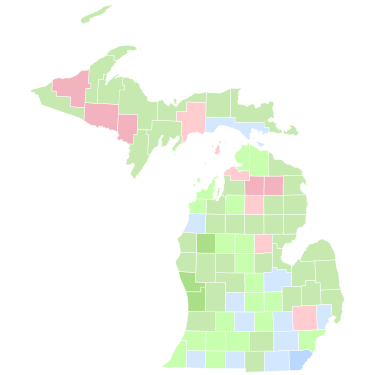

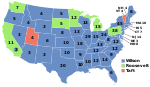

1912 United States presidential election in Michigan

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Бериг-ВентранжBérig-Vintrange Країна Франція Регіон Гранд-Ест Департамент Мозель Округ Форбак-Буле-Мозель Кантон Гростенкен Код INSEE 57063 Поштові індекси 57660 Координати 48°58′15″ пн. ш. 6°41′57″ сх. д.H G O Висота 233 - 295 м.н.р.м. Площа 8,52 км² Населення 216 (01-2020[1]) Г

Ocnele Mari Ciudad con estatus de oraș Escudo Ocnele MariUbicación de Ocnele Mari en Rumania.Coordenadas 45°05′00″N 24°19′00″E / 45.083333333333, 24.316666666667Capital Gura SuhașuluiEntidad Ciudad con estatus de oraș • País Rumania • Distrito VâlceaSuperficie • Total 25.05 km²Altitud • Media 262 m s. n. m.Población (Censo 2002[1]) • Total 3563 hab.Huso horario UTC +2Código postal...

Mimpi Anak YatimGenre Drama Roman PembuatRapi FilmsPemeran Dimas Beck Aryani Fitriana Hessel Steven Mayang Yudittia Niniek Arum Negara asalIndonesiaBahasa asliBahasa IndonesiaJmlh. musim1Jmlh. episode24 (daftar episode)ProduksiProduserGope T. SamtaniPengaturan kameraMulti-kameraDurasi60 menitRumah produksiRapi FilmsDistributorMedia Nusantara CitraRilisJaringan asliTPIRilis asli2008 –2008Pranala luarSitus web produksi Mimpi Anak Yatim adalah sinetron Indonesia produksi Rapi Films yang d...

Building in Manhattan, New York United States historic placeAmerican Fine Arts SocietyU.S. National Register of Historic PlacesNew York City Landmark No. 0255 (2008)Location215 West 57th Street, Manhattan, New YorkCoordinates40°45′58″N 73°58′50″W / 40.7662°N 73.9806°W / 40.7662; -73.9806Built1891ArchitectHenry J. HardenberghArchitectural styleFrench RenaissanceNRHP reference No.80002662[1]NYCL No.0255Significant datesAd...

Darmansyah Darmansyah (lahir 23 September 1969) adalah seorang birokrat Indonesia kelahiran Desa Ujung Karang, Kecamatan Sawang, Kabupaten Aceh Selatan. Ia lulus dari SDN Ujong Karang pada 1981, SMP Negeri Sawang pada 1984, SPG (Sekolah Pendidikan Guru) Negeri Tapaktuan pada 1987 dan S-1 FKIP Unaya Banda Aceh pada 1994. Ia mula-mula bekerja sebagai Guru SD Negeri Ladang Baro, Kecamatan Meukek, Aceh Selatan dari 1988 sampai 2000. 12 tahun kemudian, ia memegang jabatan struktural di Dinas Pendi...

Indian actor For the American author, see Vijay Menon (writer). Vijay MenonBornLondon, England, United KingdomOccupationsFilm directoreditoractordubbing artistYears active1981–present Vijay Menon is an Indian actor, editor, director and dubbing artist in Malayalam cinema.[1] He has acted in more than 100 films in South Indian languages. He mainly handles in character roles and supporting roles. He has won Kerala State Film Awards thrice, including Kerala State Film Award for Be...

Badminton has been part of the Arab Games since 1999 in Amman, Jordan. Syria tops the medal table, having won 15 gold medals, 3 silvers and 3 bronze medals. Algeria won four golds and two silvers while Egypt won a gold, three silvers and six bronzes. Sudan won its first medal in badminton at the 2007 Pan Arab Games. At the 2011 Arab Games in Qatar, badminton was removed from the sports program. The sport later returned to the 2023 Arab Games in Algiers, Algeria with the team events discontinu...

2012 United States Senate election in New Mexico ← 2006 November 6, 2012 (2012-11-06) 2018 → Nominee Martin Heinrich Heather Wilson Party Democratic Republican Popular vote 395,717 351,259 Percentage 51.01% 45.28% County resultsHeinrich: 40–50% 50–60% 60–70% 70–80%Wilson: 40–50% &#...

C. 1550 painting by Tintoretto VisitationArtistTintorettoYearc. 1550TypeOil on canvasDimensions250 cm × 146 cm (98 in × 57 in)LocationPinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna, Bologna, Italy Visitation or Visitation with Saint Joseph and Saint Zacharias is a c.1550 painting by Tintoretto, now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna.[1] Originally an altarpiece in the church of San Pietro Martire in Bologna, where it was first recorded in the seventeen...

Esta página cita fontes, mas que não cobrem todo o conteúdo. Ajude a inserir referências. Conteúdo não verificável pode ser removido.—Encontre fontes: ABW • CAPES • Google (N • L • A) (Setembro de 2023) Movimento Nacional Feminino(MNF) Movimento Nacional Feminino Lema Por Deus e pela Pátria Tipo Organização feminina Fundação 28 de abril de 1961 Extinção 1974 Sede Rua Presidente Arriaga 6, Lisboa Cecília Supico Pi...

Manx speaker, teacher, and author John GellJuan y GeillBorn1899Liverpool, LancashireDied23 November 1983Port St Mary, Isle of ManOccupation(s)Teacher and authorOrganizationYn Çheshaght GhailckaghKnown forAuthor of Conversational ManxJohn Gell (1899 – 1983), also known as Jack Gell or Juan y Geill was a Manx speaker, teacher, and author who was involved with the revival of the Manx Language on the Isle of Man in the 20th century. His book Conversational Manx, A Series of G...

Circuito Brasileiro Banco do Brasil Sub-21 Voleibol País Brasil Confederação CBV Informações gerais Temporadas Primeira temporada 2003 (M) e 2003 (F) Temporada atual 2022 (M) e 2022 (F) Campeonato Brasileiro de Voleibol de Praia Sub-21 é o principal torneio de Vôlei de praia nacional na categoria Sub-21, também denominado como Circuito Brasileiro Banco do Brasil Sub-21 ou CBBVP SUB 21 , disputada anualmente e organizada pela Confederação Brasileira de Voleibol (CBV) e supervis...

Le tableau des médailles des Jeux paralympiques d'été de 1964 donne le classement, selon le nombre de médailles gagnées par leurs athlètes, des pays participant aux Jeux paralympiques d'été de 1964, tenus à Tokyo, au Japon, du 3 au 12 novembre 1964. Tableau des médailles Pays organisateur (Japon) Tableau des médailles Rang Nation Or Argent Bronze Total 1er États-Unis 50 41 32 123 2e Grande-Bretagne 18 23 20 61 3e Italie 14 15 16 45 4e Australie 12 11 7 30 5...

Month in 1918 1918 January February March April May June July August September October November December << August 1918 >> Su Mo Tu We Th Fr Sa 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 The following events occurred in August 1918: Australian General John Monash received a knighthood on the battlefield in France. Painting by Will Longstaff depicting German prisoners of war on the first day of the Battle of Amiens. Painting by Fred...

Nayanar saint Nami Nandi AdigalPersonalBornEmapperur, Over a period this name was changed as ThiruneipairReligionHinduismPhilosophyShaivism, BhaktiHonorsNayanar saint, Nami Nandi Adigal, also spelt as Naminandi adigal, Naminandi adikal and Naminanti Atikal, and also known as Naminandi and Naminandhi, is a Nayanar saint, venerated in the Hindu sect of Shaivism. He is generally counted as the 27th in the list of 63 Nayanars.[1] Life The life of Nami Nandi Adigal is described in the Tami...

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Maseno School – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Public school in Maseno, KenyaMaseno SchoolLocationMasenoKenyaInformationTypePublicMottoPerseverance shall win throughEstablished1906Web...

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article is an autobiography or has been extensively edited by the subject or by someone connected to the subject. It may need editing to conform to Wikipedia's neutral point of view policy. There may be relevant discussion on the talk page. (January 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) This article includes a list ...

British stand-up comedian and writer This article is an orphan, as no other articles link to it. Please introduce links to this page from related articles; try the Find link tool for suggestions. (April 2021) Tony CowardsBorn (1973-05-27) 27 May 1973 (age 50)Ipswich, SuffolkMediumStand up,NationalityBritishWebsite[1] Tony Cowards (born 27 May 1973) is a British stand-up comedian and writer, currently living in the East Midlands. Background Born in Ipswich in 1973, Cowards lived in Suffol...

本條目存在以下問題,請協助改善本條目或在討論頁針對議題發表看法。 此條目體裁可能更适合散文而非列表。 (2021年3月15日)如果合适请协助将此条目改写为散文。查看编辑帮助。 此條目需要补充更多来源。 (2016年6月15日)请协助補充多方面可靠来源以改善这篇条目,无法查证的内容可能會因為异议提出而被移除。致使用者:请搜索一下条目的标题(来源搜索:X-Plane — ...

This article relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this article by adding secondary or tertiary sources. Find sources: Arakan Liberation Party – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Political party in Myanmar Arakan Liberation Party ရခိုင်ပြည် လွတ်မြောက်ရေး ပါတီPresidentKhaing Ray KhaingVice ...