Schrödinger picture

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Балтазар Особисті дані Повне ім'я Освальдо Сільва Народження 14 січня 1926(1926-01-14)[1] Сантус, Сан-Паулу, Бразилія Смерть 25 березня 1997(1997-03-25) (71 рік) Сан-Паулу, Бразилія Зріст 174 см Вага 75 кг Громадянство Бразилія Позиція нападник Професіональні клуби* Роки К

У Вікіпедії є статті про інших людей із прізвищем Вокер. Біллі Вокер Особисті дані Народження 29 жовтня 1897(1897-10-29) Вензбері, Велика Британія Смерть 28 листопада 1964(1964-11-28) (67 років) Шеффілд, Велика Британія Зріст 183 см Громадянство Англія Позиція нападник Юнацькі к

This article is about the hamlet in Hampshire. For the hamlet in Wiltshire, see Clanville, Wiltshire. Human settlement in EnglandClanvilleCoronation Hall, ClanvilleClanvilleLocation within HampshireOS grid referenceSU319488Civil parishPenton GraftonDistrictTest ValleyShire countyHampshireRegionSouth EastCountryEnglandSovereign stateUnited KingdomPost townANDOVERPostcode districtSP11Dialling code01264PoliceHampshire and Isle of WightFireHampshire and Isle of Wight...

Local chief executive Governor of PampangaGobernador ning PampangaSeal of the Province of PampangaIncumbentDennis Pinedasince June 30, 2019StyleThe HonorableResidenceSan Fernando, PampangaSeatPampanga Provincial CapitolTerm length3 years, not eligible for re-election immediately after three consecutive termsConstituting instrumentPhilippine Commission Act No. 83Republic Act No. 7160Inaugural holderJosé Avilés (Spanish administration)Ceferino Joven (Civil Government)Formation1812 (start...

1946 film Idea GirlTheatrical release posterDirected byWill JasonScreenplay byCharles R. MarionElwood UllmanStory byGladys ShelleyProduced byWill CowanStarringJess BarkerJulie BishopAlan MowbrayGeorge DolenzJoan ShawleeLaura Deane DuttonCinematographyGeorge RobinsonEdited byOtto LudwigProductioncompanyUniversal PicturesDistributed byUniversal PicturesRelease date February 8, 1946 (1946-02-08) Running time60 minutesCountryUnited StatesLanguageEnglish Idea Girl is a 1946 American...

2017 Kannada comedy film by Dayal Padmanabhan Satya HarishchandraDirected byDayal PadmanabhanWritten byDayal PadmanabhanStory bySri SwamijiBased onSingh vs Kaur (2013) (Punjabi film)Produced byK. ManjuStarringSharan Sanchita Padukone Bhavana RaoCinematographyFaizal AliMusic byArjun JanyaProductioncompanyK. Manju CinemaasRelease date 20 October 2017 (2017-10-20) CountryIndiaLanguageKannada Satya Harishchandra is a 2017 Indian Kannada language romantic comedy film written and dir...

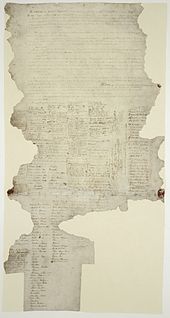

Legal process by which Māori seek redress for breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi Claims and settlements under the Treaty of Waitangi (Māori: Te Tiriti o Waitangi) have been a significant feature of New Zealand politics since the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 and the Waitangi Tribunal that was established by that act to hear claims. Successive governments have increasingly provided formal legal and political opportunity for Māori to seek redress for what are seen as breaches by the Crown of g...

甲賀(こうが) 三郎(さぶろう) 誕生 井﨑 能為1893年(明治26年)10月5日[1]滋賀県蒲生郡日野町[1]死没 (1945-02-14) 1945年2月14日(51歳没)岡山県岡山市墓地 慈眼寺職業 小説家言語 日本語国籍 日本最終学歴 東京帝国大学工科大学化学科卒業活動期間 1923年 - 1945年ジャンル 探偵小説、探偵戯曲文学活動 本格派[1]代表作 『支倉事件』デビュー作 『真珠塔�...

Matthias ApiariusInformación personalNacimiento c. Siglo XV Berching (Alemania) Fallecimiento Septiembre de 1554 Berna (Suiza) Nacionalidad Alemana y suizaInformación profesionalOcupación Compositor e impresor [editar datos en Wikidata] Matías Apiarius, también llamado Matthias Biener (Berching, Alto Palatinado, c. 1495 - Berna, septiembre de 1554) fue un editor e impresor suizo de origen alemán. Introdujo la imprenta en Berna y fue uno de los principales e...

2006 studio album by BenightedIdentisickStudio album by BenightedReleasedFebruary 10, 2006GenreBrutal death metalLength41:07LabelAdipocère RecordsBenighted chronology Insane Cephalic Production(2004) Identisick(2006) Icon(2007) Identisick is the fourth studio album by French death metal band Benighted. It was released by Adipocère Records on February 10, 2006.[1] Track listing No.TitleLength1.Nemesis3:322.Collapse3:473.Identisick3:544.Sex-Addicted3:555.Mourning Affliction4:1...

Coastal mountain range in California King RangeBeach & surf, King Range National Conservation AreaHighest pointPeakKing PeakElevation4,091 ft (1,247 m)[1]Coordinates40°09′25″N 124°07′27″W / 40.15694°N 124.12417°W / 40.15694; -124.12417[1]GeographyLocation of the King Range in California[2]Show map of CaliforniaKing Range (California) (the United States)Show map of the United States CountryUnited StatesStateCaliforn...

Deputi Bidang Pengembangan Destinasi Pariwisata Kementerian Pariwisata Republik IndonesiaGambaran umumDasar hukumPeraturan Presiden Nomor 19 Tahun 2015 Peraturan Presiden Nomor 93 Tahun 2017Susunan organisasiDeputiDadang Rizki Ratman[1]Kantor pusatGedung Sapta PesonaJalan Medan Merdeka Barat No. 17Jakarta Pusat 10110DKI Jakarta, IndonesiaSitus webwww.kemenpar.go.id Deputi Bidang Pengembangan Destinasi Pariwisata merupakan unsur pelaksana pada Kementerian Pariwisata Republik Indon...

Mexican politician Gabriel ValenciaGeneral Gabriel Valencia, in an 1848 lithographPresident of MexicoIn officeDecember 30, 1845 – 2 January 1846Preceded byJosé Joaquín de HerreraSucceeded byMariano Paredes Gabriel Valencia (c.1794 – March 25, 1848)[1] was a Mexican soldier in the early years of the Republic. From December 30, 1845 to January 2, 1846 he served as interim president of Mexico. He was the President of the Chamber of Deputies in 1843.[2]...

У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. SCCP (значения). SCCP — Skinny Client Control Protocol, корпоративный (проприетарный) VoIP-протокол для управления взаимодействием между оконечными телефонным устройствами и сервером телефонной системы - IP-АТС. По своим функциям SCCP аналоги...

BossSingel oleh Fifth Harmonydari album ReflectionDirilis7 Juli 2014 (2014-07-07)Direkam The Venice Studio (Venice, California) The Record Plant (Los Angeles) Genre Dance-pop hip hop R&B Durasi2:51Label Epic Syco Pencipta Eric Frederic Joe Spargur Daniel Kyriakides Gamal Lewis Jacob Kasher Taylor Parks Produser Frederic Spargur Kyriakides Kronologi singel Fifth Harmony Miss Movin' On (2013) Boss (2014) Sledgehammer (2014) Video musikBoss di YouTube Boss adalah sebuah lagu yang direka...

S-33 Messenger Role Racer/UtilityType of aircraft National origin United States Manufacturer Sikorsky First flight 1925 Number built 2 The Sikorsky S-33 Messenger was an American two-seat sesqiuplane designed and built by the Sikorsky Manufacturing Corporation in 1925. The first of two examples built participated in the Sixth Pulitzer Trophy Race at Mitchel Field, Long Island, New York on October 12, 1925 and was piloted by Al Krapish, an employee of Sikorsky.[1] The first aircraft is...

Election in Pennsylvania Main article: 1988 United States presidential election 1988 United States presidential election in Pennsylvania ← 1984 November 8, 1988 1992 → Nominee George H. W. Bush Michael Dukakis Party Republican Democratic Home state Texas Massachusetts Running mate Dan Quayle Lloyd Bentsen Electoral vote 25 0 Popular vote 2,300,087 2,194,944 Percentage 50.70% 48.39% County Results Bush 50-60% 60-70% &...

Editorial category of manga This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Seinen manga – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (September 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Part of a series onAnime and manga Anime History Voice acting Companies Studios Original video animation...

Fictional prime minister of the United Kingdom in House of Cards This article is about the fictional politician. For Oxford University academic, see Francis Fortescue Urquhart. Fictional character Francis Ewan UrquhartHouse of Cards characterFirst appearanceHouse of CardsLast appearanceThe Final CutCreated byMichael DobbsPortrayed byIan RichardsonIn-universe informationOccupationChief Whip Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury (Series 1) Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain...

American railroad Not to be confused with Central Illinois Railroad. Illinois Central RailroadCombined route map of the Chicago Central and Pacific (red) and Illinois Central (blue) railroads in 1996.[1]Two Illinois Central EMD SD70s lead a train at Homewood, IllinoisOverviewHeadquartersChicago, IllinoisReporting markICLocaleMidwest to Gulf Coast, United StatesDates of operation1851–1999SuccessorCanadian National RailwayTechnicalTrack gauge4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,4...