Anti-Nigerian sentiment

|

Read other articles:

Pakistani military college Command and Staff Collegeادارہَِ سالاری و عمال عسکریCommand and Staff College EmblemFormer namesArmy Staff CollegeMottoPersian: پیر شو بیاموز سعدی (romanized: Pir Sho Biyamooz Saadi)English: Grow old, learning Saadi Urdu: سیکھتے ہوئے عمر رسیدہ ہو جاؤ، سعدیTypeStaff collegeEstablished1905; 118 years ago (1905) (as the Army Staff College in Deolali, British India)CommandantMaj. Gen. Na...

Sekretariat Perdana Menteri Melayu:Jabatan Perdana Menteri Jawi:جابتن ڤردان منتريLambangInformasi KementerianDibentukJuli 1957; 66 tahun lalu (1957-07)[1]Wilayah hukumPemerintah MalaysiaKantor pusatPerdana Putra, Pusat Administrasi Pemerintah Federal, 62502 PutrajayaPegawai33,802 (2018)Anggaran tahunan4,048,073,200 Ringgit (2020)MenteriMohd. Naim Mokhtar, Menteri AgamaAzalina Othman Said, Menteri Hukum dan Reformasi KelembagaanArmizan Mohd Ali, Menteri Sabah dan Sa...

La base aérienne 265 Rocamadour est une ancienne base aérienne utilisée par l'Armée de l'air française sur le Causse de Gramat dans le Lot (46). Elle se situe à 8 km au nord-ouest de la ville de Gramat dans le Lot. Elle était aussi nommée Camp de Lacalm, ou Viroulou par les locaux, du nom de lieux-dits proches. Historique Années 1940 Mise en construction en 1939 par le Service des Poudres, cette annexe de la Poudrerie de Bergerac n'a jamais vu le jour car les événements de la ...

Berikut adalah Daftar perguruan tinggi swasta di Jawa Tengah, yang pembinaannya berada di bawah Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Republik Indonesia dan Perguruan Tinggi Swasta Keagamaan, yang pembinaannya berada di bawah Kementerian Agama. Daftar ini tidak termasuk Perguruan Tinggi Kedinasan yang pembinaannya berada dibawah masing-masing kementerian/lembaga. Universitas[1] Nama Tahun Berdiri Lokasi Situs Universitas Muhammadiyah Magelang 1964 Kabupaten Magelang https://unimma.ac....

Francisco Cuesta. Francisco Cuesta Gómez (Valencia, 1890 – aldaar, 1921) was een Spaans componist. Levensloop Hij studeerde aan het Conservatorio Superior de Música de Valencia, samen met onder anderen José Iturbi en Leopoldo Querol. Vooral werd hij bekend door de interpretaties van La vida breve van Manuel de Falla en Goyescas van Enrique Granados. Hij bewerkte een oorspronkelijk orkestwerk Dos Danzas Valencianas zelf voor banda en gebruikte daarvoor een uitgebreide instrumentatie. Comp...

Masjid Agung Darussalam Sumbawa BaratBerkas:Tugusyukur.jpgMasjid Agung Darussalam Sumbawa BaratAgamaAfiliasi agamaIslamLokasiLokasiKabupaten Sumbawa Barat, Nusa Tenggara Barat, IndonesiaKoordinat8°45′12.3865″S 116°51′5.1984″E / 8.753440694°S 116.851444000°E / -8.753440694; 116.851444000Koordinat: 8°45′12.3865″S 116°51′5.1984″E / 8.753440694°S 116.851444000°E / -8.753440694; 116.851444000ArsitekturJenisMasjidPeletakan batu...

Human settlement in EnglandFreelandSt Mary the Virgin parish churchFreelandLocation within OxfordshirePopulation1,490 (2021 Census)OS grid referenceSP4112Civil parishFreelandDistrictWest OxfordshireShire countyOxfordshireRegionSouth EastCountryEnglandSovereign stateUnited KingdomPost townWitneyPostcode districtOX29Dialling code01993PoliceThames ValleyFireOxfordshireAmbulanceSouth Central UK ParliamentWitneyWebsiteFreeland Village Website List of places ...

طواف عمان 2018 تفاصيل السباقسلسلة9. طواف عمانمنافسةطواف آسيا للدراجات 2018 2.HCمراحل6التواريخ13 – 18 فبراير 2018المسافات914٫5 كمالبلد سلطنة عماننقطة البدايةعمر علينقطة النهايةالفرق18عدد المتسابقين في البداية126عدد المتسابقين في النهاية116متوسط السرعة40٫055 كم/سالمنصةالفائز أليكس�...

Maria Sri Wulan Sumardjono (lahir 23 April 1943) adalah seorang akademisi Indonesia. Saat ini, ia menjabat sebagai guru besar hukum agraria untuk Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM). Sebelumnya, ia pernah menjadi Dekan UGM periode 1991-1997. Selain itu, ia merupakan Kepala Pusat Pengkajian Hukum Tanah (PPHT) Fakultas Hukum UGM sejak 1995. Cukup banyak posisi yang pernah dijabati oleh Maria sebagai seorang akademisi, peneliti, pejabat pembuat keputusan maupun sebagai pemakalah dalam seminar agraria....

Family of cartilaginous fishes Eagle rayTemporal range: 100.5–0 Ma PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N Late Cretaceous to Recent[1] Bull ray (Aetomylaeus bovinus) Scientific classification Domain: Eukaryota Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Chondrichthyes Subclass: Elasmobranchii Superorder: Batoidea Order: Myliobatiformes Suborder: Myliobatoidei Superfamily: Dasyatoidea Family: MyliobatidaeBonaparte, 1838 Genera Aetomylaeus Myliobatis The eagle rays are a group of cartilag...

2006 single by Ne-Yo This article is about the Ne-Yo song. For the T-ara song, see Sexy Love (T-ara song). For the Kylie Minogue song, see Kiss Me Once. Sexy LoveSingle by Ne-Yofrom the album In My Own Words B-sideSign Me UpReleasedJune 6, 2006 (2006-06-06)GenreR&BLength3:40LabelDef JamSongwriter(s)Shaffer SmithMikkel S. EriksenTor Erik HermansenProducer(s)StargateNe-Yo singles chronology When You're Mad (2006) Sexy Love (2006) Because of You (2007) Sexy Love is the fourth ...

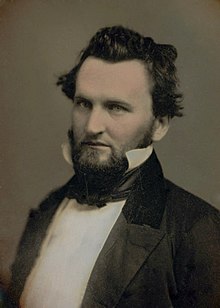

J. Neely JohnsonGubernur California 4Masa jabatan9 Januari 1856 – 8 Januari 1858WakilRobert M. AndersonPendahuluJohn BiglerPenggantiJohn B. Weller Informasi pribadiLahir(1825-08-02)2 Agustus 1825County Gibson, IndianaMeninggal31 Agustus 1872(1872-08-31) (umur 47)Salt Lake City, Wilayah UtahPartai politikKnow NothingSuami/istriMary ZabriskieProfesiAhli hukum, pengacara, politikusSunting kotak info • L • B John Neely Johnson (2 Agustus 1825 – 31...

Consejo de Gabinete de la República de Panamá LocalizaciónPaís Panamá PanamáInformación generalJurisdicción PanamáTipo consejo de ministrosSede Palacio de las GarzasSistema República presidencialistaOrganizaciónPresidente Laurentino CortizoVicepresidente José Gabriel CarrizoComposición 15 Ministros y 3 Ministros ConsejerosDepende de Gobierno de PanamáHistoriaFundación 4 de noviembre de 1903[editar datos en Wikidata] El Consejo de Ministros de Panamá, también co...

National flag LebanonUseNational flag and ensign Proportion2:3Adopted7 December 1943; 80 years ago (1943-12-07)DesignA horizontal triband of red, white (double height) and red; charged with a green Lebanese cedar tree.Designed byHenri Philippe Pharaoun Vertical flag of Lebanon The national flag of Lebanon (Arabic: علم لبنان) is formed of two horizontal red stripes enveloping a horizontal white stripe. The white stripe is twice the height (width) of the red ones ...

Artikel ini perlu diwikifikasi agar memenuhi standar kualitas Wikipedia. Anda dapat memberikan bantuan berupa penambahan pranala dalam, atau dengan merapikan tata letak dari artikel ini. Untuk keterangan lebih lanjut, klik [tampil] di bagian kanan. Mengganti markah HTML dengan markah wiki bila dimungkinkan. Tambahkan pranala wiki. Bila dirasa perlu, buatlah pautan ke artikel wiki lainnya dengan cara menambahkan [[ dan ]] pada kata yang bersangkutan (lihat WP:LINK untuk keterangan lebih lanjut...

Dana Veldáková Datos personalesNacimiento Rožňava (Eslovaquia)3 de junio de 1981Nacionalidad(es) EslovacaCarrera deportivaDeporte Atletismo Medallero Atletismo Eslovaquia Eslovaquia Europeo Pista Cubierta BronceParís 2011Triple salto [editar datos en Wikidata] Dana Veldáková (Eslovaquia, 3 de junio de 1981) es una atleta eslovaca especializada en la prueba de triple salto, en la que consiguió...

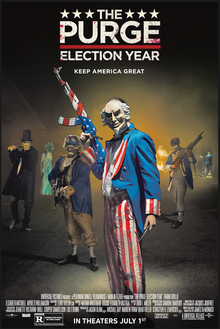

2016 film directed by James DeMonaco The Purge: Election YearTheatrical release posterDirected byJames DeMonacoWritten byJames DeMonacoProduced by Jason Blum Michael Bay Andrew Form Brad Fuller Sébastien K. Lemercier Starring Frank Grillo Elizabeth Mitchell Mykelti Williamson CinematographyJacques JouffretEdited byTodd E. MillerMusic byNathan WhiteheadProductioncompanies Platinum Dunes Blumhouse Productions Man in a Tree Productions Distributed byUniversal PicturesRelease date July 1,&#...

Football team of University of Colorado Boulder Colorado Buffaloes football2023 Colorado Buffaloes football team First season1890Athletic directorRick GeorgeHead coachDeion Sanders 1st season, 4–8 (.333)StadiumFolsom Field(capacity: 50,183[1])Year built1924[1]Field surfaceNatural GrassLocationBoulder, ColoradoNCAA divisionDivision I FBSConferencePac-12Past conferencesIndependent (1890–1892, 1905)CFA (1893–1904, 1906–1908)RMAC (1909–1937)Skyline (1938–1947)Big Eight...

Halaman ini berisi artikel tentang planet. Untuk dewa Romawi, lihat Jupiter (mitologi). Untuk kegunaan lain, lihat Jupiter (disambiguasi). Jupiter Tampilan Jupiter dalam warna alaminya pada bulan Januari 2023. Terlihat salah satu bulan Jupiter, Ganimede yang berada di kanan bawah Bintik Merah Raksasa.[a]PenamaanPelafalan/ˈdʒuːpɪtər/ ( simak)[1]Nama alternatifMusytari (المشتري)Kata sifat bahasa InggrisJovianCiri-ciri orbit[5]Epos J2000Aphelion816.5...

Municipality in La Paz Department, BoliviaCoroico MunicipalityMunicipalityCoroicoCoroico MunicipalityLocation within BoliviaCoordinates: 16°10′S 67°50′W / 16.167°S 67.833°W / -16.167; -67.833Country BoliviaDepartmentLa Paz DepartmentProvinceNor Yungas ProvinceSeatCoroicoGovernment • MayorManuel Yani Calle (2007)Population (2001) • Total12,237Time zoneUTC-4 (BOT) Coroico Municipality is the first municipal section of the Nor Yun...