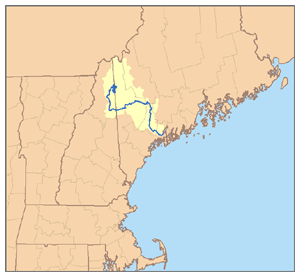

Androscoggin River

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Международное энергетическое агентство члены ассоциированные страны страны в процессе присоединения Членство 29 участников Штаб-квартира Париж Локация Франция Тип организации Международная организация Руководители...

County in Mississippi, United States Not to be confused with Union, Mississippi. County in MississippiUnion CountyCountyThe Union County courthouse in New AlbanyLocation within the U.S. state of MississippiMississippi's location within the U.S.Coordinates: 34°29′N 89°00′W / 34.49°N 89°W / 34.49; -89Country United StatesState MississippiFoundedJuly 7, 1870SeatNew AlbanyLargest cityNew AlbanyArea • Total417 sq mi (1,080 km2)&#...

Dibujos preparatorios Versión en el Museo del Prado. Versión en el Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de la Argentina. El aguafuerte Hasta su abuelo es un grabado de la serie Los Caprichos del pintor español Francisco de Goya. Está numerado con el número 39 en la serie de 80 estampas. Se publicó en 1799. Interpretaciones de la estampa Existen varios manuscritos contemporáneos que explican las láminas de los Caprichos. El que se encuentra en el Museo del Prado se tiene como autógrafo de G...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Shear. Cornelius Lott ShearBiographieNaissance 26 mars 1865AlbanyDécès 2 février 1956 (à 90 ans)Los AngelesNationalité américaineFormation Université du Nebraska à LincolnActivités Botaniste, mycologueAutres informationsA travaillé pour Département de l'Agriculture des États-UnisAbréviation en botanique Shearmodifier - modifier le code - modifier Wikidata Cornelius Lott Shear est un botaniste américain, né le 26 mars 1865 à Coeymans Hollo...

Mass media involvement Russo-Georgian War Main topics Background Prelude Timeline Responsibility Information war Cyberattacks International reaction Protests Humanitarian impact / response Financial impact Infrastructure damage Reconstruction efforts International recognition ofAbkhazia and South Ossetia Occupied territories of Georgia Related topics Georgian–Ossetian conflict Abkhaz–Georgian conflict Transnistria conflict Belarusian–Russian Milk War Russo–Ukrainian War Secon...

Herdenking in Cherasco, 2007 Het Verdrag van Parijs, ook wel Vrede van Parijs genoemd, was een vredesverdrag op 15 mei 1796 tussen revolutionair Frankrijk en het door generaal Napoleon Bonaparte verslagen Italiaanse koninkrijk Piëmont-Sardinië. Het verdrag volgde op de Wapenstilstand van Cherasco van 28 april 1796. In 1792 voegde Piëmont-Sardinië zich bij de Eerste Coalitie tegen Frankrijk, nadat de Fransen de Piëmonts-Sardijnse regio Savoye hadden bezet en geannexeerd. Franse troepen on...

محمود عبد الوهاب آمنة معلومات شخصية الميلاد 3 يناير 1983 (العمر 40 سنة)حلب الطول 1.77 م (5 قدم 9 1⁄2 بوصة) مركز اللعب وسط الجنسية سوريا معلومات النادي النادي الحالي الاتحاد السوري الرقم 17 مسيرة الشباب سنوات فريق الحرية السوري المسيرة الاحترافية1 سنوات فريق مشاركات (أ

2013 video game 2013 video gameForza Motorsport 5Cover art featuring the McLaren P1 racing through PragueDeveloper(s)Turn 10 StudiosPublisher(s)Microsoft StudiosDirector(s)Dan GreenawaltProducer(s)Barry FeatherRyan B. CooperDesigner(s)Rhett MathisWilliam GieseElliott LyonsProgrammer(s)Daniel AdentChris TectorComposer(s)Lance HayesSeriesForza MotorsportPlatform(s)Xbox OneReleaseNovember 22, 2013Genre(s)RacingMode(s)Single-player, multiplayer Forza Motorsport 5 is a 2013 racing video game devel...

Hasidic rebbe (1914–1996) RabbiAvrohom Yitzchok KohnHa'KohenPersonalBorn4 January 1914Safed, Ottoman EmpireDied8 December 1996ReligionJudaismParentsAharon David Kohn (father)Sheindel Bracha (mother)Yahrtzeit27 KislevDynastyToldos Aharon Rabbi Avrohom Yitzchok Kohn (Hebrew: אברהם יצחק קאהן) (4 January 1914 – 8 December 1996) was a Hasidic rabbi and founder of the Toldos Aharon Hasidim.[1] He was the son-in-law of Rabbi Aharon Roth, and the Toldos Avrohom Yitzchok is na...

Right-wing political parties in Pakistan Not to be confused with Muslim League (Pakistan). Pakistan Muslim League پاکستان مسلم لیگAbbreviationPMLHistorical leadersNurul AminPir Pagarah VIIAbdul Qayyum KhanFounderAyub Khan (1962)[1]Founded1962; 61 years ago (1962)Preceded byMLIdeologyConservatism (Pakistan)Economic liberalismFiscal conservatismNationalismFactions:CentrismPro-presidentialismPro-parliamentarismPolitics of PakistanPolitical partiesElec...

Halston is a 2019 American biographical documentary film directed by Frédéric Tcheng. HalstonDirected byFrédéric TchengWritten byFrédéric TchengBased onHalstonProduced byRoland BallesterStephanie LevyMichael PrallFrédéric TchengStarringLiza MinnelliMarisa BerensonJoel SchumacherNaeem KhanPat ClevelandKaren BjornsonNarrated byTavi Gevinson(Chloe)CinematographyChris W. JohnsonEdited byÈlia Gasull BaladaFrédéric TchengMusic byStanley ClarkeProductioncompaniesCNN FilmsDogwoof PicturesT...

Australian journalist and sericulturist Jessie GroverBornJessie McGuire9 June 1843MelbourneDied17 March 1906 (1906-03-18) (aged 62)St KildaNationalityAustralianOccupation(s)journalist and sericulturistKnown forsilk farmerSpouseHarry Ehret GroverChildrenMontague Grover Jessie Grover (9 June 1843 – 17 March 1906) was an Australian journalist and sericulturist. She helped to set up a silk farm that would be owned and employ women, but the mulberry trees and the silk worms did no...

Islamist militant organization in Indian Administered Kashmirkill then Hizbul Mujahideenحزب المجاھدینOfficial logoFoundersMuhammad Ahsan DarHilal Ahmed MirMasood SarfrazPatron and Supreme CommanderSyed Salahuddin[1]Operational CommanderFarooq Ahmed Nali (a.k.a. Abu Ubaida) (chief operational commander in the Kashmir Valley, India)FoundationSeptember 1989 (notional)[2]Split toAnsar Ghazwat-ul-Hind[3]The Resistance Front[a]Allegiance PakistanGrou...

1994 film Dear Goddamned Friends(Cari fottutissimi amici)Film posterDirected byMario MonicelliWritten byLeo Benvenuti, Mario Monicelli, Piero De Bernardi, Suso Cecchi D'AmicoProduced byMario Cecchi Gori, Vittorio Cecchi GoriStarringPaolo Villaggio, Massimo Ceccherini, Paolo HendelCinematographyTonino NardiEdited byRuggero MastroianniMusic byRenzo ArboreDistributed byVariety DistributionRelease date February 1994 (1994-02) Running time118 minutesCountryItalyLanguageItalian Dear Godda...

American economist and sociologist Juliet Schor in CORE project interview in 2015 Juliet B. Schor (born 1955) is an American economist and Sociology Professor at Boston College.[1] She has studied trends in working time, consumerism, the relationship between work and family, women's issues and economic inequality, and concerns about climate change in the environment.[2] From 2010 to 2017, she studied the sharing economy under a large research project funded by the MacArthur Fo...

Municipality of North Macedonia Urban municipality in Northeastern, North MacedoniaMunicipality of Kriva Palanka Општина Крива ПаланкаUrban municipality FlagCoat of armsCountry North MacedoniaRegion NortheasternMunicipal seatKriva PalankaGovernment • MayorSashko Mitovski (SDSM)Area • Total480.81 km2 (185.64 sq mi)Population • Total18,059 • Density27.81/km2 (72.0/sq mi)Time zoneUTC+1 (CET)Area code031ca...

Medical conditionDural arteriovenous fistulaThis dural arteriovenous fistula of the superior sagittal sinus drains into subarachnoid veins and is classified as Borden type IIIb.Specialty Neurology Neurosurgery Symptoms Cognitive changes, including memory loss, rapidly progressive dementia, dyscalculia, hallucinations, psychomotoric slowing, apathy, disorientation, executive dysfunction Parkinsonism Headache Visual impairment, blurred vision Tinnitus Urinary incontinence Myoclonus Complication...

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) The topic of this article may not meet Wikipedia's notability guidelines for companies and organizations. Please help to demonstrate the notability of the topic by citing reliable secondary sources that are independent of the topic and provide significant coverage of it beyond a mere trivial mention. If notability cannot be shown, the articl...

Bulu tangkis mulai dipertandingkan di Olimpiade sejak tahun 1992, walaupun sebelumnya sempat dipertandingkan sebagai pertandingan eksebisi pada tahun 1972 serta tahun 1988. Kejuaraan ini diorganisir oleh Badan Bulu Tangkis Dunia (Badminton World Federation). Sejarah Olimpiade 1992 Barcelona menjadi debut pertama bulu tangkis. Partai yang digelar hanya empat, minus ganda campuran. Pada Olimpiade berikutnya di Atlanta, 1996 hingga terakhir di Tokyo, 2020 dipertandingkan 5 nomor yaitu tunggal p...

Hussain Muhammad Ershadহুসেইন মুহাম্মদ এরশাদ Pemimpin OposisiMasa jabatan3 Januari 2019 – 14 Juli 2019 PendahuluRowshan ErshadPenggantiPetahanaPresiden BangladeshMasa jabatan11 Desember 1983 – 6 Desember 1990Perdana MenteriAtaur Rahman KhanMizanur Rahman ChowdhuryMoudud AhmedKazi Zafar AhmedWakil PresidenA K M Nurul IslamMoudud AhmedShahabuddin Ahmed PendahuluAFM Ahsanuddin ChowdhuryPenggantiShahabuddin AhmedKepala Staf Angkatan Dara...