Philip Lindsley

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Batik Megamendung berwarna biru Batik Megamendung (Hanacaraka: ꦩꦺꦒꦩꦼꦤ꧀ꦢꦸꦁ) merupakan karya seni batik yang identik dan bahkan menjadi ikon batik daerah Cirebon[1] dan daerah Indonesia lainnya. Motif batik ini mempunyai kekhasan yang tidak ditemui di daerah penghasil batik lain. Bahkan karena hanya ada di Cirebon dan merupakan mahakarya, Departemen Kebudayaan dan Pariwisata akan mendaftarkan motif megamendung ke UNESCO untuk mendapatkan pengakuan sebagai salah satu ...

Artikel ini sebatang kara, artinya tidak ada artikel lain yang memiliki pranala balik ke halaman ini.Bantulah menambah pranala ke artikel ini dari artikel yang berhubungan atau coba peralatan pencari pranala.Tag ini diberikan pada Oktober 2022. Terdapat beberapa tafsir dari rujukan Alkitab untuk Elia sebagai orang Tisbe. Orang Tisbe adalah sebuah demonim yang disematkan kepada Nabi Elia dalam Perjanjian Lama (1 Raja–Raja 17:1, 1 Raja–Raja 21:17–28, 2 Raja–Raja 1:3–8 dan 2 Raja–Raj...

أندرو ر غوفان (بالإنجليزية: Andrew R. Govan) معلومات شخصية الميلاد 13 يناير 1794(1794-01-13)مقاطعة أورانجبورغ الوفاة 27 يونيو 1841 (47 سنة)مقاطعة مارشال مواطنة الولايات المتحدة الحياة العملية المدرسة الأم جامعة كارولاينا الجنوبية المهنة سياسي الحزب الحزب الجمهوري الديمق

Антоніфр. Antony Адміністрація Країна Франція Регіон Іль-де-Франс Департамент О-де-Сен Округ Антоні Код кантону 9201 Адмін. центр Антоні КонсулМандат Jean-Paul Dova1988-2014 Статистика Населення 43 219 (1999) Муніципалітетів 1 Мапа Антоні́ (фр. Antony) — кантон у Франції, в департаменті О-де-

Russian revolutionary and French-language author (1890–1947) You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Russian. Click [show] for important translation instructions. View a machine-translated version of the Russian article. Machine translation, like DeepL or Google Translate, is a useful starting point for translations, but translators must revise errors as necessary and confirm that the translation is accurate, rather than simply copy-pasting ma...

Study of the languages of Europe This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. You can help. The talk page may contain suggestions. (March 2016) This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be ch...

2014 KNSB Dutch Single Distance Championships – Women's 500 mVenueThialf, Heerenveen, NetherlandsDate26 October 2013Competitors22 skatersMedalist men Margot Boer NED Laurine van Riessen NED Thijsje Oenema NED←20132015→ 2014 Dutch Single Distance ChampionshipsMen and women500 mmenwomen1000 mmenwomen1500 mmenwomen3000 mwomen5000 mmenwomen10,000 mmenvte The women's 500 meter at the 2014 KNSB Dutch Single Distance Championships took place in Heerenveen at the Thialf ice sk...

Peta menunjukkan lokasi provinsi Lanao del Norte Lanao del Norte atau Lanao Utara merupakan sebuah provinsi di Filipina. Ibu kotanya ialah Tubod. Provinsi ini terletak di region Mindanao Utara. Provinsi ini memiliki luas wilayah 3.011,4 km² dengan memiliki jumlah penduduk 538.283 jiwa (2010). Provinsi ini memiliki angka kepadatan penduduk 179 jiwa/km². Namanya secara harfiah dapat diartikan sebagai Danau Utara dalam Bahasa Indonesia. Pembagian wilayah Secara administratif provinsi Lana...

Corte Suprema de Noruega en Oslo. La Corte Suprema de Noruega se estableció en 1815 sobre la base de la Constitución de Noruega, la prescripción de un poder judicial independiente. Se encuentra en Oslo, Noruega. Además de servir como tribunal de apelación final para civiles y penales, puede también la regla si el gabinete ha actuado de conformidad con la legislación noruega, y si la legislatura Storting se ha aprobado una ley en consonancia con la Constitución. El Tribunal Supremo de ...

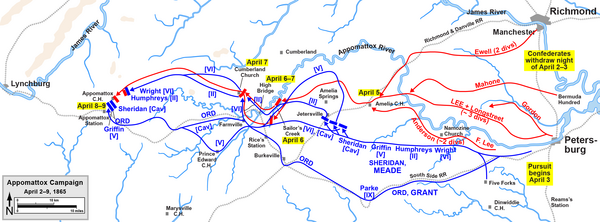

1865 battle of the American Civil War 37°21′12.5″N 78°49′38.3″W / 37.353472°N 78.827306°W / 37.353472; -78.827306 Battle of Appomattox StationPart of the American Civil WarDateApril 8, 1865 (1865-04-08)LocationAppomattox County, VirginiaResult Union victory Subsequent battle at Appomattox Court House the following dayBelligerents United States (Union) Confederate States (Confederacy)Commanders and leaders George Armstrong CusterDavid Hunter S...

Kanton (desenhista) Nome completo Luiz Canton Junior Nascimento 17 de outubro de 1959 (64 anos) Local São Paulo (capital), SP Brasil Nacionalidade Brasileira Área(s) de atuação cartunista, desenhista, animador e ilustrador Pseudônimo(s) Kanton Trabalhos de destaque O Vampiro e Bichinhos sem pelúcia da (Turma da Mônica), Eletrix (Eletropaulo) Assinatura Site oficial [1] Kanton (São Paulo, 17 de outubro de 1959) é um desenhista, animador, ilustrador e c...

Artikel ini perlu dikembangkan agar dapat memenuhi kriteria sebagai entri Wikipedia.Bantulah untuk mengembangkan artikel ini. Jika tidak dikembangkan, artikel ini akan dihapus. Artikel ini tidak memiliki referensi atau sumber tepercaya sehingga isinya tidak bisa dipastikan. Tolong bantu perbaiki artikel ini dengan menambahkan referensi yang layak. Tulisan tanpa sumber dapat dipertanyakan dan dihapus sewaktu-waktu.Cari sumber: Bou, Sojol, Donggala – berita · surat kabar&...

British peer (1922–2009) The Right HonourableThe Earl of Harrington Coat of arms of the Earls of HarringtonMember of the House of LordsLord TemporalIn office1943 – 11 November 1999Preceded byThe 10th Earl of HarringtonSucceeded bySeat abolished by theHouse of Lords Act 1999 Personal detailsBornWilliam Henry Leicester Stanhope(1922-08-24)24 August 1922Died12 April 2009(2009-04-12) (aged 86)NationalityBritishSpouses Eileen Foley Grey (m. 1942;&#...

Codex of the Quran This article is about Quran. For other uses, see Quran (disambiguation). Quran History Waḥy First revelation Asbab al-Nuzul Historicity Manuscripts Samarkand Kufic Quran Sanaa manuscript Topkapi manuscript Birmingham manuscript Divisions Surah List Meccan Medinan Āyah Juz' Muqatta'at Content Prophets Women Animals Legends Miracles Parables Science Eschatology God Reading Qāriʾ Hifz Tajwid Tarteel Ahruf Qira'at Translations List English Ahmadiyya Exegesis List Hermeneut...

Final Piala Winners Eropa 1982TurnamenPiala Winners Eropa 1981–1982 Barcelona Standard Liège 2 1 Tanggal12 Mei 1982StadionCamp Nou, BarcelonaWasitWalter Eschweiler (Jerman Barat)Penonton100.000← 1981 1983 → Final Piala Winners Eropa 1982 adalah pertandingan final ke-22 dari turnamen sepak bola Piala Winners Eropa untuk menentukan juara musim 1981–1982. Pertandingan ini mempertemukan tim Spanyol Barcelona dengan tim Belgia Standard Liège dan diselenggarakan pada 12 Mei 1...

Piala Liga Inggris 1969–19701969–70 Football League CupNegara Inggris WalesTanggal penyelenggaraan12 Agustus 1969 s.d. 7 Maret 1970Jumlah peserta92Juara bertahanSwindon TownJuaraManchester City(gelar ke-1)Tempat keduaWest Bromwich Albion← 1968–1969 1970–1971 → Piala Liga Inggris 1969–1970 adalah edisi ke-10 penyelenggaraan Piala Liga Inggris, sebuah kompetisi dengan sistem gugur untuk 92 tim terbaik di Inggris. Edisi ini dimenangkan oleh Manchester City setelah mengala...

Species of tree Vitex triflora Vitex trifolia 'Pupurea' cultivar at the Huntington Botanical Garden Scientific classification Kingdom: Plantae Clade: Tracheophytes Clade: Angiosperms Clade: Eudicots Clade: Asterids Order: Lamiales Family: Lamiaceae Genus: Vitex Species: V. triflora Binomial name Vitex trifloraVahl Synonyms Casarettoa diversifolia Walp. Macrostegia ruiziana Nees Pyrostoma ternatum G.Mey. Vitex triflora var. angustiloba Huber Vitex triflora var. coriacea Huber Vitex triflo...

Indian poet, essayist and editor This article is an orphan, as no other articles link to it. Please introduce links to this page from related articles; try the Find link tool for suggestions. (May 2023) Prabal Kumar BasuPrabal Kumar Basu in Kolkata.Born (1960-09-21) 21 September 1960 (age 63)KolkataNationalityIndianOccupationPoet Prabal Kumar Basu (Bengali: প্রবালকুমার বসু) is an Indian poet, essayist and editor. He writes in his mother tongue Bengali. Early l...

1949 film by Robert Siodmak Not to be confused with CrissCross. Criss CrossTheatrical release posterDirected byRobert SiodmakScreenplay byDaniel FuchsBased onCriss Cross1934 novelby Don Tracy[1]Produced byMichael KraikeStarringBurt LancasterYvonne De CarloDan DuryeaCinematographyFranz PlanerEdited byTed J. KentMusic byMiklós RózsaColor processBlack and whiteProductioncompanyUniversal-InternationalDistributed byUniversal-InternationalRelease dates January 19, 1949 (194...

Portuguese footballer In this Portuguese name, the first or maternal family name is Santos and the second or paternal family name is Candeias. Daniel Candeias Candeias with Rangers in 2018Personal informationFull name Daniel João Santos Candeias[1]Date of birth (1988-02-25) 25 February 1988 (age 35)[1]Place of birth Fornos de Algodres, Portugal[1]Height 1.77 m (5 ft 10 in)[1]Position(s) WingerTeam informationCurrent team KocaelisporNumb...