Makobola massacre

| |||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Saw Mill River ParkwaySaw Mill River Parkway highlighted in redRoute informationMaintained by NYSDOTLength29.83 mi[1] (48.01 km)Existed1954–presentRestrictionsNo commercial vehicles or drivers with learner's permits south of exit 43[2]Major junctionsSouth end Henry Hudson Parkway / Mosholu Parkway at the Bronx–Yonkers city lineMajor intersections Cross County Parkway in Yonkers I-87 / New York Thruway in Elmsford NY 119 in Elmsford I-87&#...

American politician CommissionerJason HolsmanMember of the Missouri Senatefrom the 7th districtIn officeJanuary 10, 2013 – January 16, 2020Preceded byJane CunninghamSucceeded byGreg Razer Personal detailsBorn (1976-03-25) March 25, 1976 (age 47)Kansas City, Missouri, U.S.Political partyDemocraticHeight6 ft 1 in (185 cm)Spouse(s)Robyn Holsman; 2 childrenResidence(s)Kansas City, Missouri, U.S.Alma materUniversity of Kansas (B. A.)Norwich University (M. A.)Occupati...

Der Nordhäuser Roland ist eine Ritterstatue am Alten Rathaus von Nordhausen, der Kreisstadt des gleichnamigen Landkreises in Thüringen. Die Rolandsfigur ist das Wahrzeichen der Stadt und symbolisierte die Reichsfreiheit von 1220 bis 1802. Nordhäuser Roland (Kopie) am Alten Rathaus Nordhäuser Roland (Original) von 1717 im Neuen Rathaus Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Geschichte 2 Gestaltung 3 Sonstiges 4 Siehe auch 5 Literatur 6 Weblinks 7 Einzelnachweise Geschichte Im Jahr 1411 wurde der Roland erst...

Nota: Para outras cidades com este nome, veja Arena (desambiguação). Arena Po Comuna Localização Arena PoLocalização de Arena Po na Itália Coordenadas 45° 4' N 9° 21' E Região Lombardia Província Pavia Características geográficas Área total 22 km² População total 1 572 hab. Densidade 71 hab./km² Altitude 61 m Outros dados Comunas limítrofes Bosnasco, Castel San Giovanni (PC), Pieve Porto Morone, Portalbera, San Zeno...

Telescópio Leonhard EulerInformações geraisOrigem do nome Leonhard EulerObservatório Observatório La SillaAdministrador Observatório de GenebraTipo de telescópio reflectorDados técnicosDiâmetro 1,2 mGeografiaLocalização Norte Chico ChileCoordenadas 29° 15′ 34″ S, 70° 43′ 59″ Oeditar - editar código-fonte - editar Wikidata O Telescópio Leonhard Euler, ou Telescópio Suíço EULER, é um telescópio refletor totalmente automático de 1,2 metros, construído e operado...

István IVIstván IV digambarkan di Kronik PiktumRaja Hungaria dan Kroasiaditentang oleh István IIIBerkuasa1163–1165Penobatan27 Januari 1163PendahuluLászló IIPenerusIstván IIIInformasi pribadiKelahiranskt. 1133Kematian11 April (usia 31-32)Zemun, SerbiaWangsaWangsa ÁrpádAyahBéla II dari HungariaIbuIlonaPasanganMaria KomnenaAgamaKatolik Roma István IV (bahasa Hungaria: IV. István, bahasa Kroasia: Stjepan IV, bahasa Slowakia: Štefan IV; skt. 1133 – 11 April...

San SimoneJazGeografia fisicaLocalizzazionemare Adriatico Coordinate43°32′37″N 15°56′03″E / 43.543611°N 15.934167°E43.543611; 15.934167Coordinate: 43°32′37″N 15°56′03″E / 43.543611°N 15.934167°E43.543611; 15.934167 Superficie0,137[1] km² Sviluppo costiero2,07[1] km Altitudine massima40,3[2] m s.l.m. Geografia politicaStato Croazia RegioneRegione di Sebenico e Tenin ComuneRogosnizza CartografiaSan S...

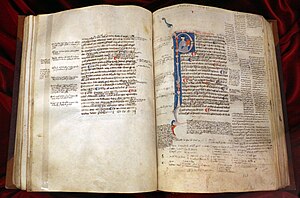

Manuskrip Analisa Dasar (Analytica Priora) dalam bahasa Latin, sekitar tahun 1290, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Italia. Analytiká Prótera ( Yunani: Ἀναλυτικὰ Πρότερα; bahasa Latin: Analytica Priora), atau Analisa Dasar (Prior Analytics) adalah karya Aristoteles yang disusun sekitar 350 SM tentang penalaran yang dikenal sebagai silogistik.[1] Analytiká Prótera adalah satu dari enam tulisan Aristoteles yang masih tersedia tentang logika dan metode ...

Artikel ini perlu dikembangkan agar dapat memenuhi kriteria sebagai entri Wikipedia.Bantulah untuk mengembangkan artikel ini. Jika tidak dikembangkan, artikel ini akan dihapus. Universitas Putra Indonesia YPTK PadangMotoMelangkah Lebih MajuJenisPerguruan Tinggi SwastaDidirikan23 September 1985 (sebagai sekolah tinggi)2001 (sebagai universitas)RektorProf. Dr. H. Sarjon Defit, S.Kom., M.Sc.AlamatPadang, Sumatera BaratSitus webhttp://upiyptk.ac.id Herman Nawas bersama Wali Kota Padang Mahyeldi p...

Artikel ini tidak memiliki referensi atau sumber tepercaya sehingga isinya tidak bisa dipastikan. Tolong bantu perbaiki artikel ini dengan menambahkan referensi yang layak. Tulisan tanpa sumber dapat dipertanyakan dan dihapus sewaktu-waktu.Cari sumber: Benteng Van der Wijck – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTOR Benteng Van der WijckNama sebagaimana tercantum dalamSistem Registrasi Nasional Cagar BudayaBenteng Van der Wijk di Gombong, Kebu...

2014 greatest hits album by RoxetteRoxette XXX – The 30 Biggest HitsGreatest hits album by RoxetteReleased3 November 2014Recorded1987–2012GenrePopLabelRoxette RecordingsParlophoneWarner Music GroupProducerClarence ÖfwermanPer GessleMarie FredrikssonMichael IlbertChristoffer LundquistRoxette chronology Live: Travelling the World(2013) Roxette XXX – The 30 Biggest Hits(2014) The RoxBox!: A Collection of Roxette's Greatest Songs(2015) Roxette XXX – The 30 Biggest Hits[1]...

Motor racing circuit in Lincolnshire, England This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Cadwell Park – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Cadwell ParkLocationLincolnshire, EnglandTime zoneGMT (UTC+0)BST (April–October, UTC+1)Coo...

Indian television actress and internet personality (born 1997) Urfi JavedJaved in 2021BornUrfi Javed (1997-10-15) 15 October 1997 (age 26)Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, IndiaAlma materAmity University, NoidaOccupationsActressinternet personalityYears active2016–present Uorfi Javed (born 15 October 1997; formerly Urfi Javed), is an Indian television actress and social media personality. Known for her unique fashion sense and social media presence, Javed began her career with roles in...

Prosperity goddess worshiped in the Mekong Delta region Bà Chúa Xứ statue in Bình An temple Temple of Bà Chúa Xứ Núi Sam today Bà Chúa Xứ (chữ Nôm: 婆主處, Vietnamese: [ɓâː cǔə sɨ̌]) or Chúa Xứ Thánh Mẫu (chữ Hán: 主處聖母, Holy Mother of the Realm) is a prosperity goddess worshiped in the Mekong Delta region as part of Vietnamese folk religions. She is a tutelary of business, health, and a protector of the Vietnamese border. She is considered p...

Expressway in Poland connecting Gdańsk, Warsaw, Cracow and Tatra Mountains Expressway S7Droga ekspresowa S7Route information Part of E77 Length590 km (370 mi)720 km (447 mi) plannedMajor junctionsNorth end S 6 near GdańskMajor intersections S 22 near Elbląg S 5 near Ostróda (planned) S 51 near Olsztyn S 50 near Płońsk (planned) S 8 / S 2 in Warsaw S 12 near Radom S 74 near Kielce A 4 near KrakówSouth end DK 7 near Rabka LocationCountryPolandMajor...

Spanish actress This biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. Please help by adding reliable sources. Contentious material about living persons that is unsourced or poorly sourced must be removed immediately from the article and its talk page, especially if potentially libelous.Find sources: Adriana Ugarte – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) In t...

2003 single by Beyoncé featuring Sean Paul Baby BoySingle by Beyoncé featuring Sean Paulfrom the album Dangerously in Love and Dutty Rock B-sideSummertime (remix)ReleasedAugust 3, 2003 (2003-08-03)RecordedFebruary 2003[1]Studio The Hit Factory (New York City, New York) South Beach (Miami, Florida)[2] Genre Dancehall R&B Length4:04Label Columbia Music World Songwriter(s) Beyoncé Knowles Scott Storch Sean Paul Henriques Robert Waller Shawn Carter Producer(s...

Practice of hanging paintings in inverted orientation Most paintings are intended to be hung in a precise orientation, defining an upper part and a lower part. Some paintings are displayed upside down, sometimes by mistake since the image does not represent an easily recognizable oriented subject and lacks a signature or by a deliberate decision of the exhibitor. Examples New York City as exhibited (

Japanese arcade game This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Waccha PriMagi! – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (October 2021) (Learn ho...

William A. WilliamsBornWilliam Williams(1836-05-26)May 26, 1836DiedMay 21, 1901(1901-05-21) (aged 64)New York CityBurial placeCalvary Cemetery (Queens)NationalityAmericanOther namesGullielmus WilliamsWilliam Augustine Willyams/WillymsEducationPontifical Urban UniversityOccupation(s)Barber, educator, sacristan, and librarianKnown forFirst openly Black Catholic seminarian from the United States Part of a series onBlack Catholicism1892 Colored Catholic Congress Overview Pope: Fran...