Kawaiisu

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Piala Super RusiaMulai digelar2003WilayahRusia (RFU)Jumlah tim2Juara bertahan CSKA Moscow (gelar ke-5)Tim tersukses CSKA Moscow (5 kali) Piala Super Rusia (bahasa Rusia: Суперкубок России) adalah sebuah pertandingan sepak bola tahunan. Nama resmi dari kompetisi ini adalah Piala Super Rusia TransTeleCom (bahasa Rusia: Суперкубок России). Kedua klub yang berpartisipasi merupakan pemegang gelar juara Liga Utama Rusia dan juara Piala Rusia. Jika Liga Utama ...

يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، ساهم في تطوير هذه المقالة من خلال إضافة مصادر موثوق بها. أي معلومات غير موثقة يمكن التشكيك بها وإزالتها. (ديسمبر 2018) سعد الدولة الأبهريالمناصب وزير بيانات شخصيةالميلاد 1240أبهرالوفاة 5 مارس 1291 (50/51 سنة) بغداد المهن طبيب وزير...

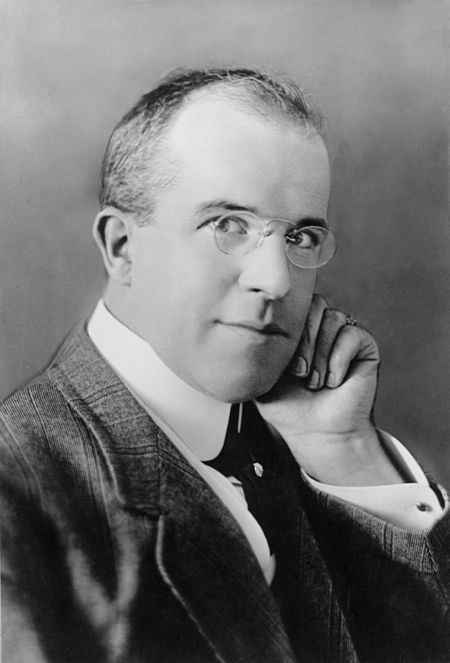

J. Stuart Blackton, 1912 James Stuart Blackton (5 Januari 1875 – 13 Agustus 1941) (biasanya dikenal sebagai J. Stuart Blackton) adalah seorang produser film Inggris Amerika yang dianggap sebagai bapak animasi Amerika Gerakan berhenti dan teknik menggambar animasi digunakan dalam film-filmnya. Ia juga seorang sutradara film bisu, dan pendiri Vitagraph Studios. Karier Blackton lahir di Sheffield, Yorkshire, Inggris, dan berimigrasi dengan keluarganya ke AS pada usia 10 tahun. Ia bekerja sebag...

Це зображення було скопійовано з російської Вікіпедії. Опис зображення виглядав так: Опис Снимок из игры The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past Джерело Снимок сделан участником Romson Час створення 17 мая 2009 года Автор зображення Игра разработана и издана компанией Nintendo Ліцензія див. нижче �...

Zahořany Zahořany (Králův Dvůr) (Tschechien) Basisdaten Staat: Tschechien Tschechien Region: Středočeský kraj Bezirk: Beroun Gemeinde: Králův Dvůr Fläche: 278,8849[1] ha Geographische Lage: 49° 57′ N, 14° 2′ O49.95361111111114.025255Koordinaten: 49° 57′ 13″ N, 14° 1′ 30″ O Höhe: 255 m n.m. Einwohner: 218 (1. März 2001) Postleitzahl: 267 01 Kfz-Kennzeichen: S Verkehr Straße: Králův Dvůr �...

2021 Indian film JojiOfficial release posterDirected byDileesh PothanWritten bySyam PushkaranBased onMacbethby William ShakespeareProduced byFahadh FaasilDileesh PothanSyam PushkaranStarring Fahadh Faasil CinematographyShyju KhalidEdited byKiran DasMusic byJustin VargheseProductioncompaniesBhavana StudiosWorking Class HeroFahadh Faasil and FriendsDistributed byAmazon Prime VideoRelease date 7 April 2021 (2021-04-07) Running time113 minutesCountryIndiaLanguageMalayalam Joji , or...

Historic church in Connecticut, United States United States historic placeSt. John's Episcopal ChurchU.S. National Register of Historic Places Show map of ConnecticutShow map of the United StatesLocation1160 Main St., East Hartford, ConnecticutCoordinates41°46′25″N 72°38′27″W / 41.77361°N 72.64083°W / 41.77361; -72.64083Area1 acre (0.40 ha)Built1867ArchitectTuckerman, Edward PotterArchitectural styleGothicNRHP reference No.83003567[1...

2016 Fates Warning album Theories of FlightStudio album by Fates WarningReleasedJuly 1, 2016 (2016-07-01)Recorded2015–2016GenreProgressive metalLength52:17LabelInside Out MusicProducerJim MatheosFates Warning chronology Darkness in a Different Light(2013) Theories of Flight(2016) Long Day Good Night(2020) Professional ratingsReview scoresSourceRatingSputnikmusic[1] Theories of Flight is the twelfth studio album by progressive metal band Fates Warning, released on ...

Species of butterfly Adelpha fessonia Sucking on a banana top Scientific classification Domain: Eukaryota Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Arthropoda Class: Insecta Order: Lepidoptera Family: Nymphalidae Genus: Adelpha Species: A. fessonia Binomial name Adelpha fessoniaHewitson, 1847 Adelpha fessonia, the band-celled sister or Mexican sister, is a species of butterfly of the family Nymphalidae. It is found in Panama north through Central America to Mexico. It is a periodic resident in the lower...

Trường Đại học Sư phạm Kỹ thuật Thành phố Hồ Chí MinhSư phạm Kỹ thuậtCổng trường Đại học Sư phạm Kỹ thuật Thành phố Hồ Chí MinhĐịa chỉ1 Võ Văn Ngân, Phường Linh Chiểu, Thành phố Thủ Đức, Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh, Việt NamThông tinTên khácSPK (mã trường)LoạiĐại học công lập, tự chủ về tài chínhKhẩu hiệuNhân bản - Sáng tạo - Hội nhậpThành lập1962Hiệu trưởngKhông cóWebsit...

One of two divisions of the Australian Army 2nd DivisionActive1915–19191921–19441948–1960 1965–presentCountryAustraliaBranchAustralian Army ReserveTypeReserve divisionSize5 brigadesMarch'Pozieres' (arr Allis)EngagementsWorld War I Gallipoli campaign Western Front CommandersCurrentcommanderMajor General David ThomaeNotablecommandersSir Charles RosenthalIven MackayHerbert LloydKathryn CampbellInsigniaUnit colour patchMilitary unit The 2nd Division of the Australian Army, also known as t...

1952 short stories by Daphne du Maurier The Birds and Other Stories The 1952 first UK edition under its original title, The Apple TreeAuthorDaphne du MaurierOriginal titleThe Apple TreeCover artistVal BiroCountryUnited KingdomLanguageEnglishPublisherGollancz[1]Publication date1952[1]Media typeHardbackPages264[1]OCLC1278358 The Birds and Other Stories is a collection of stories by the British author Daphne du Maurier. It was originally published by Gollan...

Norwegian sports club Football clubAltaFull nameAlta IdrettsforeningFounded29 May 1927; 96 years ago (1927-05-29)GroundAlta Idrettspark, FinnmarkshallenCapacity3,000ChairmanTron Møller NatlandHead coachVidar JohnsenLeague2. divisjon20232. divisjon group 2, 6th of 14 Home colours Away colours Alta Idrettsforening is a sports club from Alta, Norway. The club is most known for its association football department, which played in the 1. divisjon until 2014. Alta currently plays...

2024年夏季奥林匹克运动会纳米比亚代表團纳米比亚国旗IOC編碼NAMNOC納米比亞國家奧林匹克委員會網站olympic.org.na(英文)2024年夏季奥林匹克运动会(巴黎)2024年7月26日至8月11日運動員1參賽項目1个大项历届奥林匹克运动会参赛记录(总结)夏季奥林匹克运动会199219962000200420082012201620202024 2024年夏季奥林匹克运动会纳米比亚代表团是纳米比亚所派出的2024年夏季奥林匹克运动会�...

Estado Federal de Loreto Estado federal no reconocido 1896 [[Archivo:|border|125px]]Bandera Territorio proclamado como parte del Estado Federal de Loreto Área controlada por el Estado peruanoCapital IquitosEntidad Estado federal no reconocido • País PerúIdioma oficial EspañolGentilicio Loretano (a)Período histórico República Aristocrática • 2 de mayode 1896 Inicio de la insurrección loretana • 10 de ...

2018–19 concert tour by Thirty Seconds to Mars The topic of this article may not meet Wikipedia's notability guideline for music. Please help to demonstrate the notability of the topic by citing reliable secondary sources that are independent of the topic and provide significant coverage of it beyond a mere trivial mention. If notability cannot be shown, the article is likely to be merged, redirected, or deleted.Find sources: Monolith Tour – news · newspapers · ...

Species of freshwater stingray Potamotrygon rex Adult Potamotrygon rex (photo by Marcelo R. De Carvalho) Scientific classification Domain: Eukaryota Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Chondrichthyes Subclass: Elasmobranchii Superorder: Batoidea Order: Myliobatiformes Family: Potamotrygonidae Genus: Potamotrygon Species: P. rex Binomial name Potamotrygon rexM. R. de Carvalho, 2016 Potamotrygon rex, the great river stingray, is a species of freshwater stingray belonging to the famil...

Employment and labour law For other uses, see Overtime (disambiguation). The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this article, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new article, as appropriate. (May 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Part of a series onOrganised labour Labour movement Timeline New unionismProletariat Social movement unionism Social democracyDemocratic socialismSocialismCo...

Condado de Hamilton Condado Ubicación del condado en IowaUbicación de Iowa en EE.UU.Coordenadas 42°22′55″N 93°42′39″O / 42.381944444444, -93.710833333333Capital Webster CityEntidad Condado • País Estados Unidos • Estado Iowa • Sede Webster CityFundación 1856Superficie • Total 1496 km² • Tierra 577 mi² 1494 km² • Agua (0.13%) 1 mi² 2 km²Población (2000) • Total 16 438&...

Dieser Artikel oder nachfolgende Abschnitt ist nicht hinreichend mit Belegen (beispielsweise Einzelnachweisen) ausgestattet. Angaben ohne ausreichenden Beleg könnten demnächst entfernt werden. Bitte hilf Wikipedia, indem du die Angaben recherchierst und gute Belege einfügst. Skizze einer Jakobsleiter Als Jakobsleiter (benannt nach der biblischen Jakobsleiter) wird in der Seefahrt eine Strickleiter bezeichnet. Jakobsleitern sind einfach aufgebaute Strick- oder Tauleitern, bei denen runde Sp...