Royal Navy |

Read other articles:

この項目では、Chrome OSのオープンソース開発バージョンについて説明しています。Chromeのオープンソース開発バージョンについては「Chromium」をご覧ください。 Chromium OS 新しいタブページを表示したChromium OS (85.0.4163.0)。開発者 Googleプログラミング言語 C、C++OSの系統 Unix系, Linux, Gentoo開発状況 開発中ソースモデル オープンソースリポジトリ chromium.googlesource.com/chromiumos/ ア

لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع الحرب الروسية التركية (توضيح). الحرب الروسية العثمانية 1768-1774 جزء من الحروب الروسية العثمانية معلومات عامة التاريخ 1768-1774 الموقع أراضي ما هو الآن مولدوفا، أوكرانيا وبلغارياالثغور العثمانية على البحر الأسود النتيجة نصر روسي ساحقمعاهدة كيتشوك كا

Metro de Seúl LugarUbicación Seúl, Corea del Sur Corea del SurDescripciónTipo Metro, cercaníasInauguración 15 de agosto de 1974Características técnicasLongitud 335,1 kmLongitud red 1.108,7 kmEstaciones 328 (red urbano) 546 (total)Ancho de vía 1435 mmExplotaciónEstado En servicioN.º de líneas 16incluyendo 9 líneas de tren urbanoPasajeros 6,7 millones (2010)Operador Seoul Metro, SMRT, Metro 9, Incheon Subway, Korail, Korail Airport Railroad, Sin Bundang LineMapa Mapa de rutas ...

Archaeopteris adalah jenis genus pohon prasejarah progymnospermae yang punah, dengan daun yang mirip pakis. Fosil pohon ini telah ditemukan di berbagai lapisan batuan, yang berasal dari sekitar 383 hingga 323 juta tahun yang lalu. Fosil tertua yang ditemukan berusia sekitar 385 juta tahun,[1] dan pohon ini pernah tersebar di seluruh dunia. Archaeopteris Periode Devon Akhir hingga Karbon Awal PreЄ Є O S D C P T J K Pg N ↓ Archaeopteris hibernicaTaksonomiDivisiTracheophytaSubfil...

ECIL Bus Stationఇ.సి.ఐ.ఏల్ బస్ స్టేషన్TerminusECIL Bus StationGeneral informationLocationKamala Nagar, Kushaiguda Secunderabad, TelanganaCoordinates17°28′21″N 78°34′12″E / 17.472402°N 78.569907°E / 17.472402; 78.569907Owned byTelangana State Road Transport CorporationPlatforms2Bus routes ECIL - Alwal - Medchal, ECIL - JBS, ECIL- Neredmet- Malkajgiri - Secunderabad, ECIL-Afzalgunj, ECIL-Mehedipatnam, ECIL-Keesara, Secunderab...

Species of geometer moth in subfamily Sterrhinae For the moth from Australia and Indonesia with this name, see Scopula perlata. Cream wave Scientific classification Domain: Eukaryota Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Arthropoda Class: Insecta Order: Lepidoptera Family: Geometridae Genus: Scopula Species: S. floslactata Binomial name Scopula floslactata(Haworth, 1809) Synonyms Phalaena brunneata Goeze, 1781 Phalaena cariata Schrank, 1802 Phalaena concatenata Hufnagel, 1767 Phalaena dentilinearia ...

American gridiron football player (born 1954) Condredge HollowayHolloway in 2023Born: (1954-01-24) January 24, 1954 (age 69)Huntsville, Alabama, U.S.Career informationStatusRetiredCFL statusAmericanPosition(s)QuarterbackCollegeUniversity of TennesseeHigh schoolLee (Huntsville, Alabama)NFL draft1975 / Round: 12 / Pick: 306(By the New England Patriots)Career historyAs player1975–1980Ottawa Rough Riders1981–1986Toronto Argonauts1987BC Lions Career highlights and...

French Guianan footballer (born 1986) Ludovic Baal Baal in 2015Personal informationDate of birth (1986-05-24) 24 May 1986 (age 37)Place of birth Cayenne, French Guiana, FranceHeight 1.76 m (5 ft 9 in)Position(s) Left-backSenior career*Years Team Apps (Gls)2005–2008 Le Mans B 74 (11)2007–2011 Le Mans 102 (3)2011–2015 Lens 130 (2)2015–2019 Rennes 74 (0)2016–2019 Rennes B 5 (0)2019–2021 Brest 18 (0)2022 Concarneau 11 (0)International career‡2012– French Guiana...

Artikel ini tidak memiliki referensi atau sumber tepercaya sehingga isinya tidak bisa dipastikan. Tolong bantu perbaiki artikel ini dengan menambahkan referensi yang layak. Tulisan tanpa sumber dapat dipertanyakan dan dihapus sewaktu-waktu.Cari sumber: Pembantu Letnan Dua TNI – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTOR Pangkat militer Indonesia Angkatan Darat Angkatan Laut Angkatan Udara Perwira Jenderal Besar Laksamana Besar Marsekal Besa...

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Georges Weill et Weill. Georges WeillGeorges Weill (2013)BiographieNaissance 31 janvier 1934StrasbourgDécès 14 juin 2022 (à 88 ans)Neuilly-sur-SeineNom de naissance Georges Jenas WeillNationalité françaiseFormation École nationale des chartesActivités Archiviste, historienAutres informationsDistinctions Chevalier de l'ordre national du MériteOfficier des Arts et des LettresChevalier de la Légion d'honneurmodifier - modifier le code - modif...

Grassland Woodland Roundshaw Downs is a 52.7-hectare (130-acre) Site of Metropolitan Importance for Nature Conservation Roundshaw in the London Boroughs of Sutton and Croydon.[1][2] An area of 19.6 hectares in Sutton is also a local nature reserve.[3][4] In the nineteenth century the area was farmland, and in the first half of the twentieth it was Croydon Airport.[5] Most of the site is a mixture of chalk and neutral grassland.[1] Areas of unimp...

Painting by Frederic Leighton The DaphnephoriaArtistFrederic LeightonYear1876 (1876)MediumOil on canvasDimensions226 cm × 518 cm (89 in × 204 in)LocationLady Lever Art GalleryAccessionLL 3632 The Daphnephoria is an oil painting by Frederic Leighton, first exhibited in 1876. Background The Daphenphoria was a triumphal procession held every ninth year at Thebes in honour of Apollo, to whom the laurel was sacred, and to commemorate also a victory ...

Beber tribal confederation in Morocco Barghawata Confederacy744–1058Barghawata Confederacy (blue)Common languagesBerber (Lisan al-Gharbi)Religion Official : Islam-influenced Traditional Berber religion (adopted by 12 tribes)Other : Islam (Khariji)(adopted by 17 tribes)GovernmentMonarchyTribal confederacy(29 tribes)King • 744 Tarif al-Matghari• 961 Abu Mansur Isa Historical eraMiddle Ages• Established 744• Disestablished 1058 Preceded by Succee...

For the legal term, see high crimes and misdemeanours. 1973 filmHigh CrimeItalian film poster for High CrimeDirected byEnzo G. CastellariScreenplay by Tito Carpi Gianfranco Clerici Vincenzo Mannino Enzo G. Castellari Leonardo Martín[1] Story byLeonardo Martín[1]Produced byEdmondo Amati[1]Starring Franco Nero James Whitmore Fernando Rey CinematographyAlejandro Ulloa[1]Edited byVincenzo Tomassi[1]Music byGuido & Maurizio De Angelis[1]Product...

2017 video game 2017 video gameAnother EdenDeveloper(s)Wright Flyer StudiosPublisher(s)Wright Flyer Studios[a]Director(s)Daisuke TakaKaito FuruyaMasato KatoProducer(s)Daisuke TakaSouichi TamuraArtist(s)Takahito ExaShinwoo CheiWriter(s)Masato KatoComposer(s)Shunsuke TsuchiyaMariam AbounnasrYasunori MitsudaPlatform(s)AndroidiOSMicrosoft WindowsNintendo SwitchReleaseAndroid, iOSJP: April 12, 2017NA: January 28, 2019EU: June 26, 2019Microsoft WindowsWW: March 31, 2021JP: December 6, 2021N...

Political party in Spain Unite SumarAbbreviationSMRLeaderYolanda DíazFounded28 March 2022 (as an association)9 June 2023 (as an electoral coalition)Preceded byUnidas PodemosMás PaísIdeologyDemocratic socialism[1]Green politics[1]Direct democracy[1]Political positionLeft-wing[7] to far-left[13]MembersSee compositionCongress of Deputies26 / 350Senate3 / 266European Parliament3 / 59Election symbol Websitewww.sumarfuturo.info (association)w...

This article is about the district in Kerala. For other uses, see Kannur (disambiguation). District in Kerala, IndiaKannur district Cannanore districtDistrict Clockwise from top:Vayalapra lake, Thalassery cuisine, St. Angelo Fort, Mappila Bay, Muzhappilangad Beach, Kannur International Airport.Nickname: Crown of KeralaLocation in KeralaKannur districtCoordinates: 11°52′08″N 75°21′20″E / 11.8689°N 75.35546°E / 11.8689; 75.35546Country IndiaStateKer...

American politician Ralph Delahaye PaineMember of the New Hampshire House of RepresentativesIn office1918–1920 Personal detailsBornRalph Delahaye Paine(1871-08-28)August 28, 1871Lemont, Illinois, U.S.DiedApril 29, 1925(1925-04-29) (aged 53)Concord, New Hampshire, U.S.Political partyDemocraticAlma materYale University Ralph Delahaye Paine (August 28, 1871 – April 29, 1925)[1] was an American journalist and author popular in the early 20th century. Later, he held both elec...

MavadoInformasi latar belakangNama lahirDavid Constantine BrooksNama lainThe Real McKoy, Gully God, Gangsta Fi LifeLahir30 November 1981 (umur 42)JamaikaAsalKingston, JamaikaGenreDancehall, reggaePekerjaanSinger, DeejayTahun aktif2004 – sekarangArtis terkaitAllianceSitus webMavado@MySpace David Constantine Brooks (lahir 30 November 1981 atau populer dengan nama panggung Mavado adalah pemusik dancehall asal Jamaika. Ia dibesarkan di kawasan kumuh yang disebut Cuba di tengah komunitas Ca...

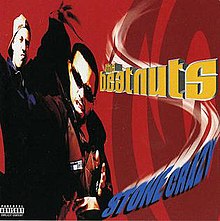

For the Beautiful People song, see If 60's Were 90's. 1997 studio album by The BeatnutsStone CrazyStudio album by The BeatnutsReleasedJune 24, 1997 (1997-06-24)RecordedAugust 1996 – February 1997StudioWorldwideGenreHip hopLength50:49LabelRelativityProducerThe BeatnutsThe Beatnuts chronology The Beatnuts: Street Level(1994) Stone Crazy(1997) Hydra Beats, Vol. 5(1997) Singles from Stone Crazy Find ThatReleased: December 24, 1996 Do You Believe?Released: March 11, 1997 O...