Pulse

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

Rare educational video game 2010 video gameeCrew Development ProgramTitle screenDeveloper(s)McDonald’s (JP)[1]Publisher(s)McDonald'sPlatform(s)Nintendo DSRelease 2010 (Japan) 17 November 2020 (archived reupload) Genre(s)Education, simulation, quizMode(s)Single-player eCrew Development Program (eCDP, Japanese: クルトレ eCDP), known unofficially as the McDonald's Training Game, is an educational video game created by McDonald's. Released for the Nintendo DS in 2010[2] inte...

Doberschau-Gaußig Vista de Doberschau Brasão Mapa Doberschau-GaußigMapa da Alemanha, posição de Doberschau-Gaußig acentuada Administração País Alemanha Estado Saxônia Região administrativa Dresden Distrito Bautzen Prefeito Alexander Fischer Partido no poder CDU Estatística Coordenadas geográficas 51° 8' 30 N 14° 8' 26 E Área 40,48 km² Altitude 220 m População 4.436[1] (31/12/2009) Densidade populacional 109,58 hab./km² Outras Informações Placa de ve...

Costa Rican football player (born 1989) In this Spanish name, the first or paternal surname is Alvarado and the second or maternal family name is Brown. Esteban Alvarado Alvarado with Costa Rica at the 2015 CONCACAF Gold CupPersonal informationFull name Esteban Alvarado Brown[1]Date of birth (1989-04-28) 28 April 1989 (age 34)[2]Place of birth Siquirres, Costa RicaHeight 1.93 m (6 ft 4 in)[2]Position(s) GoalkeeperTeam informationCurrent team...

Der Eingang des Forts Eine der zerstörten Haubitzen Fort Loncin war eines von sechs großen Festungswerken des Festungsring Lüttich; außerdem gab es sechs kleine Festungswerke. Der Ring wurde 1880 bis 1890 nach Plänen des Generals Henri Alexis Brialmont um die belgische Stadt Lüttich herum gebaut; dabei wurden erstmals Beton und Stahlbeton im größeren Umfang verwendet. Das Fort Loncin wurde 1888 gebaut. Die Besatzung bestand aus 500 Artilleristen und 80 Infanteristen. Es erhielt am 15....

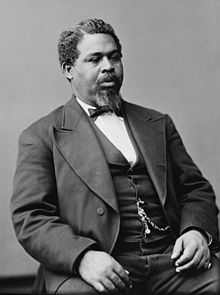

Robert Smalls Robert Smalls (5 April 1839 – 23 Februari 1915) adalah seorang pengusaha, penerbit dan politikus asal Amerika Serikat. Lahir dalam perbudakan di Beaufort, Carolina Selatan, ia membebaskan dirinya sendiri, krunya dan keluarganya pada Perang Saudara Amerika dengan mengkomandani kapal angkut Konfederasi, CSS Planter, di pelabuhan Charleston, pada 13 Mei 1862, dan berlabuh dari perairan yang dikuasai Konfederasi ke blokade AS yang berada di dekatnya. Ia kemudian meng...

Soccer clubNew York Red Bulls U-23Full nameNew York Red Bulls U-23Nickname(s)Little RedsFounded2009; 14 years ago (2009)StadiumRed Bull Training Facility[1]OwnerRed Bull GmbHHead CoachRob ElliottLeagueUSL League Two20213rd, Metropolitan DivisionPlayoffs: Conference Quarterfinals Home colors Away colors The New York Red Bulls U-23 is an American soccer team based in Harrison, New Jersey. Founded in 2009, the team plays in USL League Two, a national amateur league at t...

Madness discographyMadness performing at Bimbos in 2005.Studio albums13Live albums4Compilation albums16Video albums5EPs2Singles43Soundtrack albums2Box sets4 The discography of Madness, a British pop/ska band, comprises thirteen studio albums, sixteen compilation albums, four live albums, two soundtrack albums, two extended plays, four box sets and forty-three singles. Albums Studio albums Title Album details Chart positions Certifications(sales thresholds) UK[1] AUS[2] BEL[...

Railway station in San'yō-Onoda, Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan Habu Station埴生駅Habu Station in February 2010General informationLocationHabu, San'yō-Onoda-shi, Yamaguchi-ken 757-0012JapanCoordinates34°2′57.02″N 131°5′12.71″E / 34.0491722°N 131.0868639°E / 34.0491722; 131.0868639Owned by West Japan Railway CompanyOperated by West Japan Railway CompanyLine(s) San'yō LineDistance502.6 km (312.3 mi) from KobePlatforms...

Korean actress In this Korean name, the family name is Jeon. Jeon In-hwaBorn (1965-10-27) October 27, 1965 (age 58)Mungyeong, North Gyeongsang, South KoreaEducationChung-Ang University - B.A. in Theater and FilmOccupationActressYears active1984–presentAgentImagine AsiaSpouseYoo Dong-geunChildren2Korean nameHangul전인화Hanja錢忍和Revised RomanizationJeon In-hwaMcCune–ReischauerChŏn In-hwa Jeon In-hwa (Korean: 전인화; born October 27, 1965), is a South Korean ac...

American evolutionary molecular biologist (born 1976) Beth ShapiroShapiro in 2010BornBeth Alison Shapiro1976 (age 46–47)Allentown, Pennsylvania, U.S.Alma mater University of Georgia (BA, MA) University of Oxford (DPhil) Known forHow to Clone a Mammoth[4]Awards AAA&S Fellow (2023) MacArthur Fellowship (2009) Royal Society University Research Fellowship (2006)[1] Scientific careerFields Ancient DNA Genomics Molecular ecology[2] Institutions Unive...

Mozambican Football FederationCAFFounded1975[1]FIFA affiliation1980CAF affiliation1978PresidentFeizal SidatWebsitehttp://www.fmf.co.mz/ The Mozambican Football Federation (Portuguese: Federação Moçambicana de Futebol, FMF) is the governing body of football in Mozambique. It was founded in 1975, affiliated to FIFA in 1980 and to CAF in 1978. It organizes the national football league Moçambola and the national team. References ^ CAF and FIFA, 50 years of African football – the DVD...

Soviet Tuvan politician, journalist, and writer (1921–2010) In this name that follows Eastern Slavic naming conventions, the patronymic is Sereyevich and the family name is Shoigu. Kuzhuget ShoiguКүжүгет ШойгуBornShoygu Seree oglu Küzhüget(1921-09-24)24 September 1921Kara-Khol [ru], Tuvan People's Republic (now Republic of Tuva, Russia)Died1 December 2010(2010-12-01) (aged 89)Political partyCommunist Party of the Soviet UnionChildrenSergei, Larisa Kuzhuge...

British actor (1903–1962) For other people named Hugh Sinclair, see Hugh Sinclair (disambiguation). Hugh SinclairBorn(1903-05-19)19 May 1903London, England, UKDied29 December 1962(1962-12-29) (aged 59)Slapton, Devon, England, UKOccupationActorYears active1922–1961Spouse(s)Valerie Taylor (1930-?)Rosalie Williams (two children) Hugh Sinclair (19 May 1903 – 29 December 1962) was a British actor born in London, the son of a clergyman. He was educated at Charterhouse School and was...

Public university in Pangasinan, Philippines Not to be confused with University of Pangasinan. Pangasinan State UniversityPamantasang Pampamahalaan ng PangasinanMottoRegion's Premier University of ChoiceTypePublic Coeducational Basic and Higher education state institutionEstablishedJuly 1, 1979; 44 years ago (July 1, 1979)Academic affiliationsPASUCChairmanRonald L. AdamatPresidentElbert M. GalasStudents32,026 (2018)[1]LocationLingayen, Pangasinan, Philippines16°01′55�...

Italian professional basketball player Andrea CinciariniCinciarini with Olimpia Milano in 2018No. 20 – Pallacanestro ReggianaPositionPoint guardLeagueLega Basket Serie APersonal informationBorn (1986-06-21) 21 June 1986 (age 37)Cattolica, ItalyNationalityItalianListed height1.93 m (6 ft 4 in)Listed weight85 kg (187 lb)Career informationNBA draft2008: undraftedPlaying career2003–presentCareer history2003–2007VL Pesaro2005–2006→Senigallia2006–20...

American biologist This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article is an orphan, as no other articles link to it. Please introduce links to this page from related articles; try the Find link tool for suggestions. (September 2020) This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by i...

Slovenská futbalová liga 2016Slovenská futbalová liga Competizione Campionato slovacco di football americano Sport Football americano Edizione 2ª Organizzatore SAAF Date dal 23 aprile 2016al 3 luglio 2016 Luogo Slovacchia Partecipanti 5 Risultati Vincitore Trnava Bulldogs(1º titolo) Secondo Žilina Warriors Semi-finalisti Nitra Knights, Cassovia Steelers Statistiche Incontri disputati 15 Punti segnati 687 (45,8 per incontro) Cronologia della co...

هذه المقالة يتيمة إذ تصل إليها مقالات أخرى قليلة جدًا. فضلًا، ساعد بإضافة وصلة إليها في مقالات متعلقة بها. (أبريل 2019) رودني شيبارد معلومات شخصية الميلاد 25 نوفمبر 1967 (57 سنة) ترينيداد مواطنة الولايات المتحدة الحياة العملية المهنة مغني، وعازف قيثارة، وممثل&...

mCherry is a member of the mFruits family of monomeric red fluorescent proteins (mRFPs). As a RFP, mCherry was derived from DsRed of Discosoma sea anemones unlike green fluorescent proteins (GFPs) which are often derived from Aequorea victoria jellyfish.[1] Fluorescent proteins are used to tag components in the cell, so they can be studied using fluorescence spectroscopy and fluorescence microscopy. mCherry absorbs light between 540-590 nm and emits light in the range of 550-650&...

Josip Skoko Skoko berseragam Wigan AthleticInformasi pribadiNama lengkap Josip SkokoTanggal lahir 10 Desember 1975 (umur 48)Tempat lahir Mount Gambier, AustraliaTinggi 1,80 m (5 ft 11 in)Posisi bermain GelandangKarier junior North Geelong Warriors1992–1993 AISKarier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)1994–1995 North Geelong Warriors 32 (8)1995–1999 Hajduk Split 97 (20)1999–2003 Genk 100 (8)2003–2005 Gençlerbirliği 58 (4)2005–2008 Wigan Athletic 45 (0)2006 → Stok...