King Arthur's messianic return

|

Read other articles:

Politics of Benin Constitution Human rights Government President (List) Patrice Talon Vice President Mariam Chabi Talata Cabinet of Benin Parliament National Assembly President: Louis Vlavonou Administrative divisions Departments Communes Arrondissements Elections Recent elections Presidential: 20162021 Parliamentary: 20192023 Political parties Foreign relations Ministry of Foreign Affairs and African Integration Minister: Aurélien Agbénonci Diplomatic missions of / in Benin Passport Visa r...

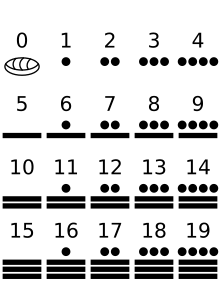

Numeración maya. Los mayas utilizaban un sistema de numeración vigesimal (de base 20) de raíz mixta, similar al de otras civilizaciones mesoamericanas.[1] El sistema numérico de rayas y puntos, que formaba la base de la numeración maya, estaba en uso en Mesoamérica desde c. 1000 a. C.;[2] los mayas lo adoptaron por el Preclásico Tardío, y añadieron el símbolo para el cero.[1][3] Esto puede haber sido la aparición más temprana conocida del...

Shinjūkyō (神獣鏡, Shinjūkyō? espejo de deidades y bestias) es un antiguo tipo de espejo de bronce redondo japonés decorado con imágenes de dioses y animales de la mitología china. En el anverso es un espejo pulido y el reverso tiene representaciones en relieve de la legendaria religión shen (神 espíritu; dios), Xian (仙 transcendent; immortal), y criaturas legendarias. Sankakuen-shinjūkyō del Tsubai Ōtsukayama kofun en Yamashiro, Tokio El estilo de espejos de bronce shinj

Stasiun Parada InglesaPlatform di Stasiun Parada InglesaLokasiAv. Luiz Dumont Villares, 1721 - Parada InglesaKoordinat23°29′14″S 46°36′32″W / 23.4870907°S 46.6088104°W / -23.4870907; -46.6088104Koordinat: 23°29′14″S 46°36′32″W / 23.4870907°S 46.6088104°W / -23.4870907; -46.6088104PemilikCompanhia do Metropolitano de São PauloJalurJalur 1-BiruJumlah peronRusukKonstruksiTinggi peronTinggiInformasi lainKode stasiunPIGSejara...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant l’Ukraine et Kiev. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Kontcha-ZaspaGéographiePays UkraineCapitale KievRaïon urbain raïon de HolossiïvCoordonnées 50° 18′ 07″ N, 30° 34′ 24″ Emodifier - modifier le code - modifier Wikidata Kontcha-Zaspa (en ukrainien : Конча-Заспа), ou parfois Koncha-Zaspa dans s...

Pour les autres navires du même nom, voir HMS Victoria. HMS Victoria Peinture du HMS Victoria en 1859 par William Frederick Mitchell. Type Navire de ligne Histoire A servi dans Royal Navy Chantier naval Portsmouth Dockyard Commandé 6 janvier 1855 Quille posée 4 avril 1856 Lancement 12 novembre 1856 Commission 2 novembre 1864 Statut 1867 : retiré du service31 mai 1893 : démoli Équipage Équipage 1000 personnes Caractéristiques techniques Longueur 79,2 m Maître-bau ...

Черні-Врихболг. Черни връх Гори Вітоша. Черні-Врих — на задньому плані.Гори Вітоша. Черні-Врих — на задньому плані. 42°33′49″ пн. ш. 23°16′42″ сх. д. / 42.56361111113877627° пн. ш. 23.27833333336077715° сх. д. / 42.56361111113877627; 23.27833333336077715Координати: 42°33′49″ пн.

?Мурашиний лев звичайний Myrmeleon formicarius Linnaeus, 1767 Біологічна класифікація Домен: Еукаріоти (Eukaryota) Царство: Тварини (Animalia) Тип: Членистоногі (Arthropoda) Клас: Комахи (Insecta) Ряд: Сітчастокрилі (Neuroptera) Надродина: Myrmeleontiformia Родина: Мурашині леви (Myrmeleontidae) Підродина: Myrmeleontinae Триба: Myrmeleontini Р

Artikel ini sudah memiliki daftar referensi, bacaan terkait, atau pranala luar, tetapi sumbernya belum jelas karena belum menyertakan kutipan pada kalimat. Mohon tingkatkan kualitas artikel ini dengan memasukkan rujukan yang lebih mendetail bila perlu. (Pelajari cara dan kapan saatnya untuk menghapus pesan templat ini) Beno Soematenojo. Beno Soematenojo (lahir di Kota Salatiga pada 1915 dan dimakamkan di Makam Ngemplak Salatiga setelah meninggal pada 31 Mei 1971) adalah salah satu pahlawan ya...

Series of Indian semi-high speed EMU train services This article is about Vande Bharat Express services offered by Indian Railways. For the EMU trainset, see Vande Bharat (trainset). Vande Bharat ExpressVande Bharat Express trains running in Blue-White and Saffron-Grey LiveriesOverviewService typeInter-city semi-high-speed railStatusActivePredecessorShatabdi Express, Jan Shatabdi Express,MEMUFirst service15 February 2019; 4 years ago (2019-02-15)Websiteindianrail.gov.inRoute...

Chileense presidentsverkiezingen 1851 Datum 25 en 26 juni 1851 Land Chili Nieuwe President Manuel Montt Torres Vorige President Manuel Bulnes Prieto Opvolging verkiezingen ← 1846 1856 → Portaal Politiek Politiek De Chileense presidentsverkiezingen van 1851 vonden op 25 en 26 juni van dat jaar plaats. De verkiezingen werden gewonnen door Manuel Montt Torres. Kandidaat Partij Stemmen Percentage Manuel Montt Torres Partido Conservador 132 81,48% José María de la ...

Natural phenomena within the Sun's atmosphere Solar activity: NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory captured this image of the X1.2 class solar flare on May 14, 2013. The image shows light with a wavelength of 304 angstroms. Solar phenomena are natural phenomena which occur within the atmosphere of the Sun. These phenomena take many forms, including solar wind, radio wave flux, solar flares, coronal mass ejections,[1] coronal heating and sunspots. These phenomena are believed to be genera...

Sharon KamPhoto: Maike HelbigBackground informationBorn (1971-08-11) August 11, 1971 (age 52)Haifa, IsraelGenresClassical music, contemporary musicOccupation(s)Solo clarinetistInstrument(s)Clarinet and basset clarinet (French system)Years active1987–presentLabelsBerlin Classics, OrfeoWebsitesharonkam.comCareer EducationJuilliard School of Music by Charles NeidichAgent(s)Impresariat Simmenauer GmbH, BerlinPress: Hasko Witte, Büro für Künstler, HamburgKnown forNumerous CDs, one D...

Este artículo o sección tiene referencias, pero necesita más para complementar su verificabilidad.Este aviso fue puesto el 17 de febrero de 2016. Gobierno Militar de Comodoro Rivadavia Territorio nacional 1944-1955 Ubicación de Zona Militar de Comodoro RivadaviaCapital Comodoro RivadaviaEntidad Territorio nacional • País ArgentinaIdioma oficial CastellanoPoblación hist. • 1951 est. 60 000 hab.Religión CatólicaHistoria • 31 de mayode 1944 De...

В Википедии есть статьи о других людях с такой фамилией, см. Макаров; Макаров, Пётр; Макаров, Пётр Иванович. Пётр Иванович Макаров Дата рождения 1765[1][2] Дата смерти 1804[1][2] Гражданство Российская империя Род деятельности офицер, прозаик, литературный крит...

Little Catworth MeadowSite of Special Scientific InterestLocationCambridgeshireGrid referenceTL 103 727[1]InterestBiologicalArea5.2 hectares[1]Notification1984[1]Location mapMagic Map Little Catworth Meadow is a 5.2-hectare (13-acre) biological Site of Special Scientific Interest between Catworth and Spaldwick in Cambridgeshire.[1][2] The meadow is traditionally managed grassland on calcareous loam, which is rare in Britain. It has mature hedgerows and ...

Rosario Mining Company Post card of San Juancito. The New York and Honduras Rosario Mining Company (NYHRMC), known as Rosario Mining Company, was an American-owned corporation that owned and operated the Rosario mine, a gold and silver producer in central Honduras and Nicaragua. History 1880 The President of Honduras, Marco Aurelio Soto, offered companies that invested in the mine in San Juancinto a 20-year exemption from all taxes. In 1880, Julius Valentine, of New York City founded the New ...

إلكا غيدو معلومات شخصية الميلاد 26 مايو 1921[1] بودابست الوفاة 19 يونيو 1985 (64 سنة) [1] بودابست مكان الدفن مقبرة اليهود في شارع قزما [لغات أخرى] مواطنة المجر الزوج إندر بيرو الحياة العملية المهنة رسامة، ومصصمة جرافك التيار تعبيرية...

This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: IG 3-Seenbahn – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) 47°48′05″N 8°11′46″E / 47.8014°N 8.1960°E / 47.8014; 8.1960 Seebrugg Station building IG 3-Seenbahnclass=notpageimage...

2016 South Korean television series Squad 38Promotional posterAlso known asTax Team 38[1]Hangul38사기동대Literal meaningFraud Task Force 38Revised Romanization38 Sagidongdae GenreRevengeCrimeBased onCharacter from InfinityOne Comics Entertainment Inc.Written byHan Jeong-hoon [ko]Directed byHan Dong-hwaStarringMa Dong-seokSeo In-gukChoi Soo-youngComposerKim Tae-seongCountry of originSouth KoreaOriginal languageKoreanNo. of episodes16ProductionExecutive producersPark Ho...