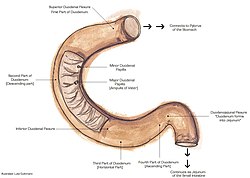

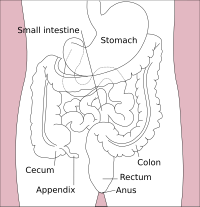

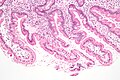

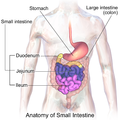

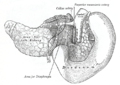

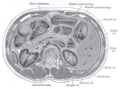

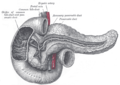

Duodenum

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Read other articles:

CenciacittàCencia – Veduta LocalizzazioneStato Etiopia RegioneNazioni, Nazionalità e Popoli del Sud ZonaGamo TerritorioCoordinate6°15′N 37°34′E / 6.25°N 37.566667°E6.25; 37.566667 (Cencia)Coordinate: 6°15′N 37°34′E / 6.25°N 37.566667°E6.25; 37.566667 (Cencia) Altitudine2 732 m s.l.m. Abitanti10 488[1] (2005) Altre informazioniFuso orarioUTC+3 CartografiaCencia Modifica dati su Wikidata · Manua...

عرض السبعينات ذاك النوع كوميديا الموقف تأليف بوني تورنر آخرين إخراج ديفيد ترينر آخرين بطولة ميلا كينيس داني ماسترسون لورا بريبون ويلمر فالديراما أشتون كوتشر توفر غريس البلد الولايات المتحدة لغة العمل الإنجليزية عدد المواسم 8 عدد الحلقات 201 مدة الحلقة 22 دقيقة

Voce principale: Cronologia della storia antica. Voce principale: Storia antica. V · D · MCronologia universaleOrigini(∞ - 3501 a.C.)Prima del big bang (∞ - 13,772 mld.) · Cronologia dell'evoluzione dell'Universo (13,772 - 4,570 mld.) · Cronologia dell'evoluzione della vita (4570 mld. - 542 mln.) · Cronologia dell'evoluzione dei vertebrati (542 - 250 mln.) · Cronologia dell'evoluzione dei mammiferi (250 - 65,5 mln.) · Cronologia dell'evo...

Trichuris trichiura Classificação científica Reino: Animalia Classe: Nematoda Ordem: Trichurida Família: Trichuridae Gênero: Trichuris Espécie: T. trichiura Nome binomial Trichuris trichiura(Owen, 1835) Trichuris trichiura é uma espécie de nematódeo do gênero Trichuris comumente encontrado parasitando o intestino grosso de humanos, causador da tricuríase.[1] Ovos Referências ↑ Stephenson, L.S.; Holland, C.V.; Cooper, E.S. (2000). «The public health significance of Trichuris tri...

Gronings (Selbstbezeichnungen: Grunnegs, Grönnegs, Grunnegers) Gesprochen in Groningen, Nord-Drenthe, Veenkolonien (Oost-Drenthe), Kollumerland (Fryslân), Niederlande Sprecher 310.000 LinguistischeKlassifikation Indogermanisch Germanisch West-Germanisch Niederdeutsch Niedersächsisch Gronings Sprachcodes ISO 639-1 – ISO 639-2 gem (sonstige Germanische Sprachen) ISO 639-3 gos Gronings (Selbstbezeichnungen Grunnegs, Grönnegs oder Grunnegers) ist eine Sammelbezeichnung für die nieders�...

Cet article est une ébauche concernant l’architecture ou l’urbanisme, l’Italie et le Piémont. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Pala AlpitourGénéralitésSurnom Palasport Olimpico, Pala Olimpico, Pala IsozakiAdresse Corso Sebastopoli, 123 10134 Turin, ItalieConstruction et ouvertureOuverture 13 décembre 2005Architecte Arata Isozaki, Pier Paolo Maggiora et Marco BrizioCoût de construction ...

هذه المقالة يتيمة إذ تصل إليها مقالات أخرى قليلة جدًا. فضلًا، ساعد بإضافة وصلة إليها في مقالات متعلقة بها. (أبريل 2019) سامانثا ريفيس معلومات شخصية الميلاد 17 يناير 1979 (44 سنة)[1] ريدوود، كاليفورنيا[1] مواطنة الولايات المتحدة الطول 173 سنتيمتر الوزن 60 كيلوغرام&...

Giải vô địch bóng đá trong nhà các câu lạc bộ châu ÁThành lập2010Khu vựcChâu Á (AFC)Số đội40Đội vô địchhiện tại Nagoya Oceans (4 lần)Câu lạc bộthành công nhất Nagoya Oceans (4 lần)Trang webOfficial website AFC Futsal Champions League 2023–24 Giải vô địch bóng đá trong nhà các câu lạc bộ châu Á (tiếng Anh: AFC Futsal Club Championship) là giải bóng đá futsal Châu Á được tổ chức hàng năm bởi Liên đ...

Автострада А5 Автострада А5Загальні даніКраїна ІталіяМережа автостради в ІталіїНомер A5 П'ємонт – Валле-д'АостаДовжина 143.4 кмНапрямок північ-південьпочаток Туринкінець ФранціяДорожнє покриття асфальтобетонOpenStreetMap ↑44874 ·R (П'ємонт, Валле-д'Аоста) Автостр�...

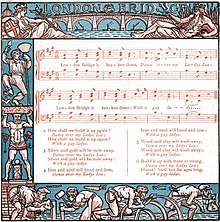

Nursery rhyme from England London Bridge Is Falling DownIllustration from Walter Crane's A Baby's Bouquet (c. 1877)Nursery rhymePublishedc. 1744Songwriter(s)Unknown London Bridge Is Falling Down (also known as My Fair Lady or London Bridge) is a traditional English nursery rhyme and singing game, which is found in different versions all over the world. It deals with the dilapidation of London Bridge and attempts, realistic or fanciful, to repair it. It may date back to bridge-related rh...

1999 Indian filmHousefullDirected byR. ParthibanWritten byR. ParthibanProduced byAbinayaKeerthanaRaakiStarringR. ParthibanVikramRojaSuvalakshmiCinematographyM. V. PanneerselvamEdited byM. N. RajaMusic byIlaiyaraajaProductioncompanyBioscope Film FramersRelease date 15 January 1999 (1999-01-15) Running time138 minutesCountryIndiaLanguageTamil Housefull is a 1999 Indian Tamil-language thriller film written and directed by R. Parthiepan. The film stars himself along with Vikram, Ro...

This article describes the 39th album in the U.S. Now! series. It should not be confused with identically-numbered albums from other Now! series. For more information, see Now That's What I Call Music! 39 and Now That's What I Call Music! discography. 2011 compilation album by various artistsNow That's What I Call Music! 39Compilation album by various artistsReleasedAugust 9, 2011Length73:03[1]LabelEMINumbered series chronology Now That's What I Call Music! 38(2011) Now That's...

2000 live album by Tangerine DreamSoundmill NavigatorCover by Edgar FroeseLive album by Tangerine DreamReleasedApril 2000Recorded1976GenreAmbient, electronica[1]Length41:46LabelTDI/EFAProducerEdgar FroeseTangerine Dream chronology Great Wall of China(1999) Soundmill Navigator(2000) Antique Dreams(2000) Professional ratingsReview scoresSourceRatingAllMusic[1] Soundmill Navigator is the sixty-ninth release and eleventh live album by Tangerine Dream. Remixed and released ...

2009 French filmThe Idiot CycleDirected byEmmanuelle Schick GarciaWritten byEmmanuelle Schick GarciaProduced byEmmanuelle Schick Garcia and Laila TahharNarrated byEmmanuelle Schick GarciaCinematographyJean Marc Abela, Florian GeyerEdited byYael BittonMusic byJoseph Guigui, David DahanProductioncompanyJPS FilmsDistributed byJPS FilmsRelease date September 25, 2009 (2009-09-25) (Canada) Running time96 minutesCountryFranceLanguagesFrenchEnglish The Idiot Cycle is a 2009 French...

Formula One racing team This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Theodore Racing – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2015) (Learn...

Chemical compound TolvaptanClinical dataTrade namesSamsca, Jinarc, Jynarque, othersOther namesOPC-41061AHFS/Drugs.comMonographMedlinePlusa609033License data EU EMA: by INN US DailyMed: Tolvaptan US FDA: Tolvaptan Pregnancycategory UK: Contraindicated Routes ofadministrationBy mouthATC codeC03XA01 (WHO) Legal statusLegal status UK: POM (Prescription only)[2][3] US: W A R N I N G {\displaystyle {\begin{array}{|}\hline W\!ARNING\...

Košarkaški klub SplitPallacanestro Segni distintivi Uniformi di gara Casa Trasferta Colori sociali Giallo, nero Dati societari Città Spalato Nazione Croazia Confederazione FIBA Europe Federazione HKS Campionato A1 Liga Fondazione 1945 Denominazione K.K. Hajduk Split (1945-49)K.K. Split (1949-67)K.K. Jugoplastika (1967-90)K.K. Slobodna Dalmacija (1991-93)K.K. Croatia Osiguranje 1993-97)K.K. Split (1997-presente) Presidente Ilija Naletilić Allenatore Slaven Rimac Impianto Arena Gripe(...

Verne MasonVerne R. MasonBornAugust 8, 1889Wapello, IowaDiedNovember 16, 1965(1965-11-16) (aged 76)Miami, FloridaNationalityAmericanOccupationphysicianKnown forassociation with Howard HughesSpouse(s)Lucy M. Ginn; Ruth Menardi Verne Rheem Mason (August 8, 1889 – November 16, 1965) was an eminent American internist and associate of Howard Hughes. Mason was chairman of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's medical advisory committee. Early years Born at Wapello, Iowa, in 1889, Mason ...

Transient housing at Camp Virginia in 2005 A kabal is the name given to a 2.6-square-kilometre (1 sq mi) patch of desert, with 3-metre-tall (10 ft) berms bulldozed to form the perimeter earthworks. Kabals are located less than 80 kilometres (50 mi) from the Iraqi border. The Kuwaiti government has cordoned off the northern part of its country, an area of more than 4,100 square kilometres (1,600 sq mi) out of 18,000 square kilometres (6,900 sq mi), where...

Arterial road in Chennai, India EVR Periyar SalaiGrand Western Trunk Road, Poonamallee High Road, State Highway Urban 86Poonamallee High Road in Park TownNamesake EVR PeriyarMaintained byHighways and Minor Ports Department Corporation of ChennaiLength8.7 mi (14.0 km)The 8.7-mile stretch refers to the stretch from Muthuswamy Bridge near Madras Medical College at Park Town in the east to the Maduravoyal Junction in the west. The stretch continues further west to a national highway (NH...